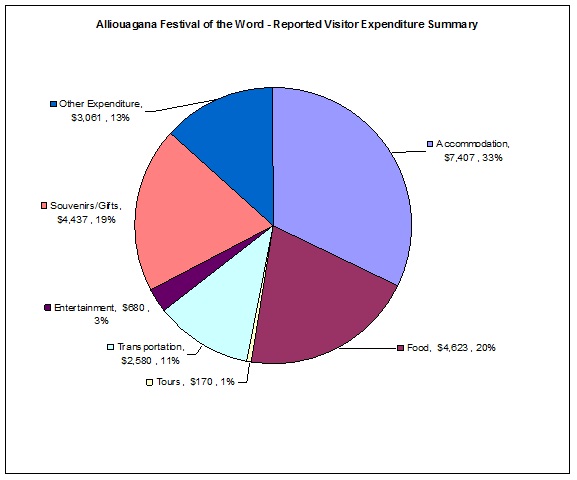

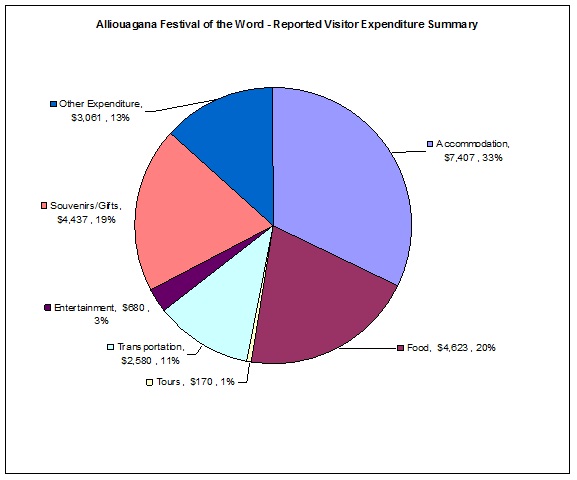

Figure 1: Visitor Expenditure, Eastern Caribbean (EC) Currency, (1 EC = .38 USD)

In charting the development of tourism on the tiny British Overseas Territory Montserrat, researchers (De Vries 1978, McElroy and de Albuquerque 1992, Weaver 1993, Gunne-Jones 1993), have documented the rapid transformation of the economy from agriculture in the 1950s to an emerging services sector including construction and tourism in the 1960s. These developments created an environment that encouraged the introduction and growth of residential tourism.

Once William H. Bramble, Leader of the Montserrat Trades and Labour Union and champion of the working classes, became a member of the Legislative Council in 1952, he concentrated on dismantling the sharecropping or metayage system which he felt exploited the labourers by not adequately compensating laborers for their work on the estates. This resulted in a movement away from agriculture in general and cotton production in particular and many estates fell idle. Gunne-Jones notes the dramatic decline in the number of agricultural workers from a high of 4,030 in 1946 to 1,859 by 1960. (4)

Bramble became Montserrat’s first Chief Minister in 1961 and his development strategy of facilitating foreign investment encouraged real estate speculators from North America to purchase many of the idle estates, particularly those along the west coast, which were then subdivided into serviced lots. These were then marketed to North Americans who wanted either winter or retirement homes in an idyllic tropical setting. This led to a building boom in Montserrat and other infrastructural developments.

Between 1960 and 1970, a total of 5,684.50 acres of former estate lands were transferred from planters to development companies. Three companies directly involved in the development and promotion of residential tourism, The West Indies Plantation Ltd., the Montserrat Real Estate Company Ltd., and the Leeward Island Development Company Ltd., purchased 4,424.68 acres. (De Vries 115-116.)

The real estate investors persuaded, the Osbornes who owned the lone hotel, the Coconut Hill Hotel then in need of refurbishing, to develop a resort hotel where potential homeowners would be able to stay. The Vue Pointe Hotel was opened in 1961. Not long after, in 1962, the Emerald Isle Hotel, another local investment initiative, added more modern facilities to the developing tourism plant on the island. These developments established the role of resort tourism as an adjunct to residential tourism on the island.

The Montserrat Report for the Year 1963 and 1964 mentions the opening of the golf course and goes on to highlight that:

Tourism also did much to assist in improving the economy of the island and its expansion was so rapid that consideration was being given to the appointment of a full-time Secretary to the Tourist Board. (Commonwealth Office 1966, 4)

By 1964, few of the lots offered by the Montserrat Real Estate Company, remained unsold. Only one house was built in 1963 but by 1966, there were 43 occupied dwellings. By 1968, the number had risen to 150. (Gunne-Jones 12).

The banking business also boomed. The single commercial banking institution on the island, the Royal Bank of Canada (there since 1917), recognized the need to expand to handle services linked to the construction industry. Construction of its new modern building began in 1964 and was completed in 1965. Barclays Bank International Ltd. Opened its Montserrat branch in 1965. One year later, the Montserrat Building Society, with a mix of local and foreign shareholders, opened its doors for business.

With the presence of residential tourists on the island came the need for other services. Interestingly, some of the new homeowners set up businesses to meet these needs.

Connie from Pennsylvania opened up “Connie’s Beauty Shop”; Ernst Herman, an importer from Boston, established the “Empire Shop” which stocked French, German and Italian wines, [and eventually included books in its inventory] and the Reierstads from Hong Kong opened two stores stocking jewels and furniture from Barbados. Glover & Mitchell (Mont) Ltd, a British grocer also opened a branch in Montserrat, and Dehaven Butterworth from New Jersey opened a soft-freeze ice cream shop. (Gunne-Jones 13).

Residential tourism encouraged the development of ancillary services, which provided jobs for Montserratians and brought the island out of abject poverty and persistent underdevelopment.

The island would never be the same again. Housing and construction patterns changed overnight…The old wooden tenements and cut-stone structures that took months to be completed were abandoned, and old seasoned masons and carpenters were drafted into the new era of speed and technology with concrete blocks, concrete mixers, and pre-fabricated shutters.

However, the boom produced a high level of skilled workmanship among the young workers who fled from agriculture into the construction industry. Masons, carpenters, plumbers, painters, electricians, surveyors now knew what an “attractive” pay packet could be like, on a regular, full time basis, and what it meant to have a guaranteed wage backed by the bank, instead of the uncertainty of food crops and seasonal cash crops. (Irish 65).

By the early 1970s, hotel accommodation was up to 88 rooms with a total of 176 beds. In addition to the Coconut Hill Hotel, the Vue Pointe Hotel, and the Emerald Isle Hotel, the accommodation stock included the Wade Inn in Plymouth, Olveston House, a remodeled estate house in Olveston, and Canadiana, offering cottages and housekeeping units in Spanish Point near the airport. (De Vries 112). During this period, Montserrat also saw several improvements in its tourism plant. Some, including the construction of condominiums, were directly related to tourism, while others, like the establishment of the Montserrat National Trust, were indirectly linked. Many of the initiatives provided support for residential tourism by establishing on-island, businesses that attracted foreign workers and clients to the island. Other efforts enhanced the quality of life for residents and the holiday experience for visitors. For most Montserratians, the benefits of residential tourism more than outweighed the negatives. Indeed, a large percentage of visitors to Montserrat speak of the warmth of the Montserrat populace, and that perceived welcoming spirit encourages repeat visits. Also, the demand for ancillary services made it possible for local entrepreneurs to be not only self-employed, but to enjoy lifestyles considered possible only by leaving the island.

The Montserrat National Trust, an NGO with mostly expatriate membership was established in 1970 with a mandate to protect and preserve the island’s beauty and natural resources as well as its historic and archaeological heritage. The Trust was responsible for the opening, in 1976, of a Museum housed in an old Sugar Mill in Richmond Hill. The Trust also coordinated the restoration of various historic sites, established trails around the island and managed the Foxes Bay Bird Sanctuary, which was declared a protected wildlife area in 1979.

The Shamrock Cinema, a foreign concern, was opened in 1971, and provided a movie theatre with seating for more than 350, and space for live shows on its stage. Since the arrival of satellite dishes, cable television, and video technology on the island, live performances on the stage eventually became more important than films in the theater. The Caribelle Inn, also foreign owned, opened for business in Parsons in the early 70s, closed by 1976, and was then reopened under new management. In 1975, work began on Shamrock Villas condominiums in Richmond Hill close to the Emerald Isle Hotel.

In reviewing the state of tourism development in Montserrat, Roger Lascelles reported that hotel/guest house accommodation stock was up to 132 rooms/cottages and 296 beds. He noted, however, that the

hotel segment of the industry is noticeably dwarfed when account is taken of the house rental business which attracts by far the biggest proportion of all visitors to the island.(8)

He goes on to describe the main recreation as swimming, sunbathing, tennis at the Vue Pointe Hotel, sailing by temporary membership at the Montserrat Yacht Club, golf, touring the island by car or on foot. He also mentions visiting such attractions as the Great Alp Waterfall, the various Soufrieres, the remains of Sugar Mills and rum distilleries, cemeteries and churches. All things considered, Montserrat had a quiet, specialized, and small-scale tourism industry.

As the 70s drew to a close, other developments included the completion of the deep-water harbour in Plymouth in 1978, which increased the potential for cruise ship passenger arrival, and the opening in 1979 of Air Studios Montserrat. Owned by former Beatles’ Manager George Martin, Air Studios was a state-of-the-art recording facility that drew top recording artists like Elton John, Paul McCartney, Jimmy Buffet, and Sting. In 1980, Montserrat became home to the American University of the Caribbean (AUC), an "off-shore" medical school. This school offered a 3 year accelerated programme in Medicine to students recruited in the USA. Faculty members were drawn primarily from the USA and the UK. Because student housing was not yet completed when the school opened, the Caribelle Inn, which had undergone several management and ownership changes was used for student housing. Many villas on the west coast and the Condominiums in Richmond Hill were rented by the teaching staff.

The early 80s also saw Montserrat engaging in a brief flirtation with health tourism. In October 1983, the Emerald Isle Hotel was converted (with foreign investment) into a "metabollic treatment centre" called the Emerald Isle Clinic. It offered treatment for cancer patients from overseas. The Clinic operated for just 16 months, during which time it went through numerous name changes. (Montserrat Times 10)

In 1984, the “North Road” was opened. It stretched 7.5 miles from St. Johns in the North to Trants in the East and provided an alternate road to the Airport. Other relevant developments in the 1980s include the Government’s purchase of two aircraft in an effort to provide improved access to the Island. The opportunity for charter tours was welcomed by visitors wanting to see neighbouring islands, and the service was able to provide added seats during peak periods, particularly during the Annual Christmas Festival, which is Montserrat’s equivalent of a Carnival. Unfortunately, this venture was short-lived due to mismanagement.

Then in 1989, the island was visited by its first destructive hurricane in more than 50 years. Hugo caused more than EC$645,750,000 of damage, and “affected about 98 per cent of the houses with 50 percent severely and 20 percent totally, leaving nearly a quarter of the population of 12,000 homeless…” (Fergus 1994, 233)

The rebuilding effort, however, took far less time than was originally anticipated and many took the opportunity to rebuild improved structures. Although some businesses, Air Studios for example, never recovered from the blow, others made good use of insurance payments. The Emerald Isle Hotel, renamed the Montserrat Springs Hotel, expanded its facility to become a resort hotel offering villas.

Following an unruly visit from Hurricane Hugo, this resort went all out to spruce itself up, enlarging and modernizing accommodations in both the main hotel and the cottages scattered along the steep hillside descending to Emerald Isle Beach. After a match on one of the lighted tennis courts or a vigorous swim in the 70-foot pool, you can unwind in the hot mineral springs or whirlpool; all-you-can-eat barbecues are another attraction (fortunately for the weak of will, only once a week). (Montserrat Springs Hotel)

Once it recovered from the destruction wrought by Hurricane Hugo in 1989, Montserrat had an even better tourist product, and prospects looked good. The new deep water harbour, completed by 1993, provided improved port facilities, and that cruise ship business provided livelihoods for taxi-drivers, tour operators and entertainers.

Many buildings in Plymouth had been restored with good use of colour and trim. Various sites around the island saw improvements, including new signs and information boards. Attention was also paid to the craft industry and the small business sector. The National Development Foundation launched a series of skills training programmes in areas like leather craft, pottery and basketry which had a positive effect on the souvenir items offered in Montserrat stores. When the volcano spluttered to life in 1995, it was in the middle of an advanced basketry workshop. The workshop was never completed because the resource person recruited from Barbados did not wait to see what else the volcano had to offer.

A report prepared by Caribbean Futures in June 1995, described Montserrat as follows:

The only Caribbean island with an Irish heritage, a virtually crime-free society, with a predominance of private villas, and rated among the top 50 mountain biking destinations in the world, Montserrat is no ordinary Caribbean holiday destination. Montserrat is the quintessence of the way the Caribbean used to be – uncrowded and unspoilt, charming and laid back, with warm, friendly and welcoming people. Nature-oriented activities (biking, hiking, bird watching and diving) are the mainstary of the Montserrat tourism industry. The peace and quiet of the country and its outstanding natural attractions are the main reasons for visiting Montserrat according to the 1994 Montserrat visitor survey. (Caribbean Futures Ltd iv)

However, on July 18, 1995, wet ash-falls in Parsons and Kinsale signaled the start of volcanic activity (Buffonge 1996). By April 1996, when the first pyroclastic flow came down Tar River Valley, Plymouth and the Southern and Eastern areas of the island were evacuated for the third and final time. In September, 1996, The historic Tar River Great House along with homes in Long Ground were burnt. (Buffonge 1997). March 1997 saw pyroclastic flows down Galways obliterating the waterfall and Galways Soufriere with its viewing platform, as well as the Galways Plantation Ruins, the subject of many studies and an important historic site that had been featured in the Smithsonian Institution’s 1992 Seeds of Change Exhibition that marked the quincentenary of Columbus’ arrival in the New World.

Nineteen lives were lost on 25 June 1997 when several villages in the eastern part of the island were destroyed (Buffonge 1998). By August, more villages and homes and the whole town of Plymouth had been consumed. The Government encouraged voluntary off island evacuation by August but people were already leaving the island. By 1997, the pre-volcano population of approximately 12,000 was down to 4,000. AUC, The Off-Shore Medical School, relocated to St. Maarten. Island Bikes and one of the two Dive operations on the island no longer operate in Montserrat.

Two-thirds of the formerly 39.6 square miles became off limits. Included in the infrastructural losses were the fairly new deep water harbour in Plymouth, a recently refurbished Hospital equipped with state of the art medical facilities, a new Government Headquarters, a new Public Library, several hotels and guest houses in Plymouth, many restaurants and business places. In the Northern Safe Zone, many businesses responded to the climate of uncertainty by operating out of temporary facilities – modified shipping containers and rapidly constructed plyboard structures. Others took to offering mobile services from the backs of pickups and other vehicles.

Plans and projects for improving tourism-related facilities on the island were shelved for the most part. Various individuals had ploughed money into developing Nature escapes for visitors (for example Paradise Estate and Gages Mountain) when the volcano woke up. Island Bikes had purchased property in Foxes Bay for hosting biking tournaments. Shelved too, were the plans for upgrading and extending Bramble’s Airport and developing an Amerindian Interpretation Centre since the extension would have engulfed an important pre-historic site. In an attempt to provide for movement in and out of the island after the loss of the airport, a helicopter and a ferry service to Antigua were put in place. According to Persad,

The major eruptions of 1995 and 1997, as well as continued volcanic activity has rendered two-thirds of Montserrat uninhabitable, and destroyed a considerable proportion of the island’s infrastructure, superstructure and natural resource product. This has resulted in a significant decline in the tourism economy, with visitor numbers currently being a mere 25% of what it was prior to the commencement of major volcanic activity in 1995. Despite these major setbacks, Montserrat continues to offer a quality tourism product to the discriminating visitor - the island’s intimate size, friendly people, verdant scenery, unique history and old time Caribbean charm. The challenge continues to be the need to effectively build a tourism industry around these fundamental strengths, by strengthening and enhancing the tourism product on the ground and also effectively promoting the island in the international marketplace.

In 1994, visitor arrivals which were in excess of 21,000 had generated more than US$24 million. By 1996, this figure had plummeted to 8,700 arrivals that generated approximately US$8.4m. This decline in tourism, once the major foreign exchange earner, was mirrored by the unavailability of foreign exchange in banks.

The negative impact of the volcanic crisis on one of the key sectors of the economy in Montserrat was widespread. The exodus from the island has left behind a cadre of mostly unskilled persons for servicing the industry. The training of the unskilled in the hospitality industry is already being addressed through the work of the National Development Foundation (NDF) and the Department for International Development (DFID). A tourism forum was hosted early in 2001, and world renowned TV chef Orlando Satchell spent a month in Montserrat training those employed in the local food and beverage industries.

While helicopter and ferry services provide a much needed link between Montserrat and the rest of the world, access to the island was not as efficient as it was before the loss of Bramble’s Airport in the East. One of the main problems was that the services were initiated as emergency services. When the ferry service was first introduced, it was accepted that churchgoing Montserratians would not avail themselves of it on a Sunday. But now potential earnings are lost because day-trippers wanting to maximise their weekend cannot be sure of getting out of Montserrat in time for connecting flights. The new airport at Geralds was opened in 2005 and eventually renamed the John A. Osborne Airport. However, it only accommodates small planes, the largest of which has to be a 19-seater.

While Montserrat faces numerous challenges, many opportunities also exist in regard to sustainable cultural tourism development. Infrastructure elements such as the new airport, the world-class Montserrat Cultural Centre, and the Montserrat Volcano Observatory are assets that are already available. In other respects, the island is left unspoiled by a legacy of mass tourism facilities. Festivals and events identified by the local residents of Montserrat are helping the community to realize their own potential and uniqueness of a culture that can then be shared with other tourists. Other tourism entities include the development of traditional festivals such as the St. Patrick’s week of activities recognizing the African and Irish heritage, the Montserrat Christmas Festival featuring the Masquerades, or the recently developed Calabash Festival, now into its third year and which focuses on various aspects of the island’s culture. These and other events convey the traditions of Montserrat (Fergus, 2006) which can also attract former residents to return to the island for heritage tourism. Developing the cultural activities on the island through music, food, and literary festivals, as well as other cultural events may help to stimulate the economy, and if effectively managed, help to restore and retain their rich heritage and traditions. Montserratians have already embraced aspects of a community participative approach as exemplified by the Christmas Festival which started in the 1960s.

Most recently, a literary festival entitled “The Alliouagana Festival of the Word” took place at the Cultural Centre in Little Bay on the island of Montserrat from November 13 to 15, 2009. Planned as a world class literary festival with presentations by internationally recognized authors and others in the publishing industry, the three day extravaganza of readings, story-telling, book-signings, music, dramatic presentations and workshops was intended to attract visitors to Montserrat from a number of markets. These included literary enthusiasts from around the world, Guadeloupe and the Montserrat diaspora.

Over 14 award winning authors presented at the festival that included visitors from over eight different countries including the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Antigua, Nevis, Guadeloupe, Barbados, and Jamaica. At the venue, 15 out of an initial 24 vendors who had indicated an interest in offering their services at the festival followed through and had items on display, to be given away or for sale.

Increased visitor arrivals contributed to revenue collection for the Government in terms of taxes paid by stay-over visitors and economic activity across the services sector (accommodation, food, transportation, crafts). A variety of vendors provided such products and services including food, beverages, telecommunication phone cards, promotional giveaways, crafts, clothing, artwork, wall hangings, guide books, brochures, publications, home made preserves, wooden clocks and other woodcraft, healing therapies, and hand made bags. Interestingly, the visitor survey reflected that very little was spent on tours EC$170 (1 EC$ = .38 USD). A summary of the visitor expenditures is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Visitor Expenditure, Eastern Caribbean (EC) Currency, (1 EC = .38 USD)

In the wake of the festival, there was evidence of a high level of satisfaction. Authors, presenters, visitors and the local community have all been complimentary although they were conscious of the shortcomings of the event and that visitors were not attracted in large numbers as hoped. The general feeling is that this is a first effort and there are expectations that the festival will grow. Because the majority of the local population had not previously attended a literary festival, local participation was mainly for those aspects of the program that were familiar to them. There was a positive turn out for the pre-festival lecture on Jamaican Dancehall Culture. The Calypso music review was another event that had a good audience turnout and the house was crowded for the dramatic presentation entitled “Pelau” by the group Plenty Plenty Yac Ya Ya.

The local economy realized the benefits of the grant funds circulating over the planning and execution period for the festival. The findings from the visitor survey indicate that in addition to the grant funds, more than an additional EC$20,000 Eastern Caribbean currency was spent on services on the island.

As a result of not being able to arrange affordable charters out of Antigua, Nevis and Guadeloupe, Montserrat lost a number of potential visitors who had an interest in attending the festival but baulked at the high cost of travel. In one instance, after receiving late news of a ferry service to start in December, one potential participant sent their regrets that the ferry service was not in operation at the time of the literary festival. There were only a few cancellations by potential visitors as a result of the increase in volcanic activity that occurred around the time of the festival. Interestingly, the festival presenters and visitors wanted to learn as much as possible about the volcano and seemed most unperturbed by the eruptions.

Vendors with unique items and services had better sales and in one case, there was a report that the weekend revenues surpassed total income for the earlier part of the year. The unofficial report of the performance of the concession stand at the Cultural Centre is that it exceeded all expectations. While business was not brisk for the Spa treatments during the festival weekend, the exposure resulted in several bookings for full treatments and an invitation to offer pamper sessions at the opening of a new branch of a book store in Antigua.

The film crew from Guadeloupe reported on the festival and apparently this has served to renew interest in Montserrat as a place to be visited. Several visits were organized for subsequent weekends and the guide that escorted the film crew is now in the business of providing this service for groups out of Guadeloupe with the need for someone to assist with the language barrier.

In addition to the economic impact of the festival, there are other social and cultural impacts that need to be noted. In several exchanges shortly after the festival, it became clear that persons who do not normally write are considering using various art forms to express themselves. The public library, as well as other collections on the island received various book donations. For example, Best of Books left material valued at EC$500 for the schools. The public library has received books donated by authors and presenters in addition to books donated by well-wishers in support of the festival.

The volunteers made suggestions for their early involvement in the planning and execution of the festival and have indicated a willingness to assist in the future. Useful suggestions were also offered by participants. For example it was suggested that:

You may want to consider putting on most of the festival activities in the afternoon (after lunch) and evening. That way, attendees at the festival will have time to explore the island in the morning and, hopefully, spend some more money on transport, food, and gift items. This will be one way to boost the economic impact of the Festival.

There were initial concerns about the venue for the festival, since the Cultural Centre is surrounded by construction work for the new town in Little Bay. Twice over the course of the weekend, participants were asked to relocate parked vehicles to allow the workmen to carry on with their tasks. However, the choice of the Cultural Centre turned out to be an ideal location for many reasons. It already has public liability insurance coverage, adequate toilet facilities and a variety of spaces to accommodate various activities. The space allowed for the efficient location of the vendor tents creating an ambience which observers have suggested should be maintained for the Christmas Festival in December. The conference room was ideal for the public lecture, author presentations and workshops, while other rooms were transformed into a lounge area for the authors and presenters as well as a press room for interviews.

One of the overarching challenges was to have a number of the service operators such as tour guides, along with ground and air transportation providers on board with the festival project. A number of meetings were held prior to the festival with the local hospitality association and eventually, in individual discussions with hoteliers, greater support was then provided. Those offering tours hesitated to offer special rates for festival attendees based on their previous experience during the St. Patrick’s Week of Celebration when the transportation costs for the tours negated any attempts at making a profit. Taxi and tour operators failed to provide flyers and brochures for display in an information booth at the festival.. It was therefore not surprising that this is the sector that was least patronized.

Concerted efforts to get attractive rates for travel to and from Montserrat were not as successful as expected. Discussions were held with regional carriers WINAIR and Fly Montserrat in an effort to arrange affordable charters or discounted rates between Nevis, Antigua, and Guadeloupe. Efforts were also made to engage a boat service out of Nevis for the festival although an agreement was not reached.

With greater experience in collaborative partnerships and problem-solving processes in place, tourism activities may include strategies that build upon the unique natural, historical, and cultural attributes distinctive to the entire Caribbean region. Furthermore, festivals and events identified by the local citizens can help the community to realize their own potential and unique culture, which can then be shared with other tourists. The participative approach for tourism development through festivals may be a suitable strategy to further develop practical and community based solutions. A successful approach to future festival development and tourism development may evolve in the recognition of the value of the experiences that the literary festival had among the community itself.

The community of local as well as external supporters made it possible to host this literary festival in Montserrat. The volunteers and those providing specialized services were essential for support during the weekend event. Future festivals will depend heavily on such collaboration if the Festival is to grow and have the kind of benefits that the island needs. Involving the community in this approach also provided a wealth of reciprocal learning opportunities among generations in the community. This in turn helped to facilitate and promote positive dialogue and change in the tourism management system while all along remaining connected to the foundation of the past.

Strong support from the Montserrat Tourist Board (MTB) especially with their assistance in advertising the Festival provided great benefits. Of particular significance was the use of the MTB’s contact person in Antigua who met the authors and some visitors and made the travel experience to Montserrat that much more positive and personal.

Planning for the festival has to start at least a year in advance. This will allow time for fundraising and for promotion of the event at home as well as abroad. Advanced planning will consequently be an effective strategy to market the activities of the event to those persons who live abroad but own homes on Montserrat. The potential is there that the non-resident home owners will stay on the island longer than the weekend and ultimately spend more money which will produce a higher economic impact for the island. The non-resident homeowners who attended this year’s festival used a wider range of services than other categories of visitors.

It is essential to have a budget item for journalists to cover the festival since this was a weakness in this first implementation. Many of the sessions have not been documented and this would have been helpful for advertising this and future festivals as well as for evaluation purposes.

Another lesson learned from this festival is that there should be written contracts for all services to avoid issues with remembering discussions and verbal agreements. It is not yet part of the business ethic on the island of Montserrat but if the festival is to sustain itself over the long term, it is important to meet internationally acceptable business standards, especially with contracts.

The souvenir booklet which was to have been a marketing tool as well as a means of raising funds was printed too late to advertise the 2009 Festival. The involvement of the diaspora in selling the pages of the booklet however, awakened interest in the event and promises were made that future festivals would be supported by Montserratians living overseas.

A grant that was provided to develop and manage the festival was spent as far as possible on local service to ensure that funds would circulate in the island economy. The use of local businesses and services came with its own challenges and highlighted the difficulties of working in a community with little competition and with persons who do not have professional business training. The festival web site

Other services contracted such as festival bags, t-shirts, and banners were not delivered at the time requested and this created scheduling difficulties for the festival. Services offered by others who had received grants under a government sponsored Tourism Challenge Fund were also used. Efforts were made to partner with the regional airline Fly Montserrat in an effort to attract as many persons to the festival as possible but no attractive rates were provided. Travel arrangements for the authors and presenters were made through a local travel operator, recently established with grant funds

Several accommodation providers offered specials for the festival and as a result promoted a longer guest stay. Furthermore, a number of homeowners who provided attractive rates for guest rooms also received festival participants. Many festival participants flying in specifically for the festival own property on the island and extended their stays for up to three weeks claiming that they would not have come to the island at this time of year if not for the festival. The results highlighted an important but overlooked market segment, that of residential tourists (those that own homes on the island, but their primary residence are at other locations) who should be more strategically targeted for future festivals.

An effort was made to have a product development and packaging workshop take place on the island to assist art and craft vendors in providing souvenir items that would be attractively packaged. It was recognized that this would have an immediate impact on vendor sales during the weekend. The project proposal was not approved for the period prior to the festival but rather for the following year. This will hopefully be of use for future festivals and its impact reflected in the increasing sales of arts and crafts.

One of the major challenges that the festival faced was that there was limited local promotion of the event. Again, efforts to get promotional activities off the ground in a timely manner were affected by deadlines not being met as planned. For example, the festival advertisement that was to have been ready for airing a month before the festival was done only a week before the festival. However, it is important to recognize that many community members came on board to assist with publicizing the festival using radio interviews on a variety of topics such as creative writing, the economic benefits of the publishing industry and the impact of literary festivals which helped to greatly bolster further interest and support.

Future research should focus on identifying the similarities and differences among the perceptions and attitude towards niche tourism development such as a literary festival. By involving local residents as well as tourists in determining the value beyond the aesthetic physical structures often associated with tourism development, a richer tourism experience such as the literary festival may be more easily sustained over the long term.

Agrusa, J. (2002). Cultural and heritage tourism, working from a bottom-up approach. 52nd TOSOK 2002 International Tourism Symposium and Conference. Buyeo County, Korea, 33-39.

Agrusa, J. (2006). The role of festivals and events in community tourism destination management. In W. Jamieson (ed.), Community Destination Management in Developing Economics, (pp. 181-192), New York: The Haworth Hospitality Press.

Agrusa, J., Coats, W., & Donlon, J. (2003). Working from a bottom-up approach: Cultural and heritage tourism, International Journal of Tourism Sciences, 3, 121-128.

British Geological Survey. (2008). Soufrière Hills volcano, Montserrat. Retrieved June 7, 2010, from http://www.bgs.ac.uk/education/montserrat/home.html.

Buffonge, Cathy. (1996). Volcano: a chronicle of Montserrat’s volcanic experience 1995-96. [Montserrat: The Author].

Buffonge, Cathy. (1997). Volcano Book Two: Into the Second Year: Montserrat’s Volcanic Experience During 1996. [Montserrat: The Author].

Buffonge, Cathy. (1998). Volcano Book Three: Events in Montserrat during 1997. [Montserrat: The Author].

Butler, R. & Hinch, T. (eds.). (1996). Tourism and indigenous peoples. London: International Thomson Business Press.

Caribbean Futures Ltd. (1995). Montserrat Tourism Marketing and Promotion Programme 1995-1997. [Port of Spain]: [Caribbean Futures Ltd].

Cassell, G. (2006). The American University of the Caribbean: Montserrat’s loss, St. Maarten’s gain. In M. C.-V. Enckevort, M. A. George & S. S. Apostolo (eds.), St. Martin Studies (pp. 61-68), University of St. Martin.

Central Intelligence Agency. (2008). The world fact book. Retrieved December 30, 2009, from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mh.html.

Commonwealth Office. 1958. Montserrat: Report for the year 1955 and 1956. London: HMSO.

Commonwealth Office. 1960. Montserrat: Report for the year 1956 and 1957. London: HMSO.

Commonwealth Office. 1966. Montserrat: Report for the year 1963 and 1965. London: HMSO.

Commonwealth Office. 1968. Montserrat: Report for the year 1964 and 1965. London: HMSO.

Craik, J. (1997). Touring Cultures-transformation of travel and theory, in C. Rojek & J. Urry (eds.), The Culture of Tourism. London: Routledge.

Davis, D., Allen, J., & Cosenza, R. (1988). Segmenting local residents by their attitudes, interests and opinions toward tourism, Journal of Travel Research, 27(2): 2-8.

De Vries, Pieter J. (1978) “Dependence and underdevelopment: tourism in the past plantation society of Montserrat, West Indies.” Thesis (Ph.D.). University of Alberta.

Derrett, R. (2000). Can festivals brand community cultural development and cultural tourism simultaneously? In J. Allen, R. Harris, L. Jago, & J. Veal (eds.), Events Beyond 2000: Setting the Agenda, Proceedings of Conference on Event Evaluation, Research and Education, Sydney.

Dwyer, L., Mellor, R., Mistilis, N., & Mules, T. (2000). A framework for assessing ‘tangible’ and ‘intangible’ impacts of events and conventions. Event Management, 6: 175-189.

Emmons, N. (2001). Festivals are salivating while celebrating food. Amusement Business, 113: 24-26.

Fergus, H. A. (2006). Montserrat: Defining moments. Toronto, Canada: Kimagic Publishing,

Fergus, Howard A. (1983). William H. Bramble: His Life and Times. Montserrat: University of the West Indies.

Fergus, Howard A. (1994). Montserrat: History of a Caribbean Colony. London: Macmillan.

Getz, D. and Frisby, W. (1988). Evaluating Management Effectiveness In Community-Run Festivals. Journal of Travel Research, 27: 22-27.

Gunne-Jones, Alan. (1993). Welcome to the Beachettes: a Study of the Development of Resdential Tourism in Montserrat. Mona: UWICED. (Occasional Paper Series; no. 2)

Hall, C.M. (1992). Hallmark tourist events: Impacts, management and planning. London: Belhaven.

Inskeep, E. (1991). Tourism planning: an integrated and sustainable development approach. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Irish, J.A.Georgre. 1990. Life in a Colonial Crucible. Labor & Social Chagne in Montserrat, 1946 – Present. New York: JAGPI Productions & Medgar Evers College, Caribbean Research Center.

Kanahele, G. S. (1991). Critical reflections on cultural values and hotel management in Hawaii, Waiaha Foundation, Honolulu, HI.

Lascelles, Roger N. (1977). Report and Recommendations to the Government of Montserrat on tourism development. [London Commonwealth Office.]

Madrigal, R. (1995). Residents perceptions and the role of government. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1): 86-102.

McDonnell, I., Allen, J., & O’Toole, W. (1999). Festival and special event management. Brisbane: John Wiley and Sons.

McElroy, J and K. de Albuquerque. (1992). The Economic Impact of Retirement Tourism in Montserrat: Some Provisional Evidence. Social and Economic Studies 41(2): 127-152.

Montserrat. Development Unit. (1998). Sustainable Development Plan: Montserrat Social and Economic Recovery Programme: A Path to Sustainable Development 1998-2000. 20 March 2001 http://www.mninet.com/devunit/sdp/

Montserrat Springs Hotel. 16 March 2001. http://www.ehi.com/travel/carib/dominica/caribbean-montserrat-springs-hotel and-villas.htm.

Montserrat Times. (1985). Manor Memorial Hospital: How Did it Happen on Montserrat. 4 April. 10.

Montserrat Tourist Board. (2008). Welcome to our home. Retrieved May 16, 2010, from http://www.visitmontserrat.php?categoryid=2

Montserrat. Department of Statistics (1983). Extract from Montserrat Visitor Survey 1983. Plymouth: Statistics Office.

Montserrat. Statistics Office. (1982). Tourism Report 1981. Plymouth: Statistics Office.

Montserrat. Statistics Office. (1983). Tourism Report 1982. Plymouth: Statistics Office.

Montserrat. Statistics Office. (1994). [Arrivals by Month & Mode of Travel Tourism Report 1980-1993]. Plymouth: Statistics Office.

Montserrat. Statistics Office. (2000). GDP by Economic Activity at Factor Cost and Constant Prices 1990-1999.

Moscardo, G. (1999). Making visitors mindful: principles for creating sustainable visitor experiences through effective communication. Champaign, IL: Sagamore Publishing,

O’Sullivan, D. & Jackson, M. J. (2002). Festival tourism: A contributor to sustainable local economic development? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 10(4): 325-342.

Ott, Gernott. (1994). Montserrat Visitor Survey 1993/1994. St. Michael, Barbados: CTO.

Pearce, P., Moscardo, G., & Ross, G. (1996). Tourism community relationships. Oxford: Pergamon.

Pulsipher, L. M. (2001). Our ‘maroon’ in the new-lost landscapes of Montserrat. Geographical Review, American Geographical Society, 91: 131-142.

Pulsipher, Lydia and Lindsey Holderfield. (2000). “Guilt Trips: Misperceiving the Landscapes of ‘Paradise’.” Southeastern Division of the Association of American Geographers, November, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Quinn, B. (2006). Problematising ‘Festival Tourism’; Arts festivals and sustainable development in Ireland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 14(3): 288-306.

Robinson, M., Picard, D., & Long, P. (2004). Festival tourism: Producing, translating, and consuming expressions of culture(s). Event Management, 8: 187-189.

Sawyer, Stephanie. (1980). Report and Recommendations on Visit to Montserrat. [s.l.]: [s.n.]

Seaton, T. & Bennett, M. (1996). The marketing of tourism products: concepts, issues and cases. Boston: International Thompson Business Press.

Taylor, David G. P. (2000). “British Colonial Policy in the Caribbean: the Insoluble Dilemma - the Case of Montserrat.” Round Table July Issue 335. Academic Search Elite.

Tikkanen, I. (2008). Internationalization process of a music festival: Case Kuhmo Chamber Music Festival. Journal of Euromarketing, 17(2): 127-139.

Travel Industry Association of America. (2003). The historic/cultural traveler. Washington, DC: TIA

U.S. Department of State. (1997). Montserrat - Travel Warning. 17 March, 2001.

Weaver, David B. (1995). “Alternative Tourism in Montserrat.” Tourism Management 16(8): 593-604.

Wheeler, Marion M. (1988). Montserrat West Indies: A chronological history. [Plymouth]: Montserrat National Trust.

Yu, Y. & Turco, D. (2000). Issues in tourism event economic impact studies: The case of the Albuquerque international balloon fiesta. Current issues in tourism, 3(2), 138-149.

© Gracelyn Cassell, 2012

HTML last revised 24th May, 2012.

Return to Conference papers.