Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) has in recent years emerged as a new paradigm in the conduct of scientific investigations. It bridges the gap between the traditional scientific approach and practice through community engagement and socialization by the involvement of a wide group of constituencies in the research process—in essence (CBPR) is about equity and access.

Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) is a collaborative approach to research that combines research methods on inquiry with community capacity building strategies to bridge the gap between knowledge produced through research and what is practiced in communities through health partners, academic partners and community partners.

Israel et. al (1998) has identified nine key principals of CBPR that support successful research partnerships:

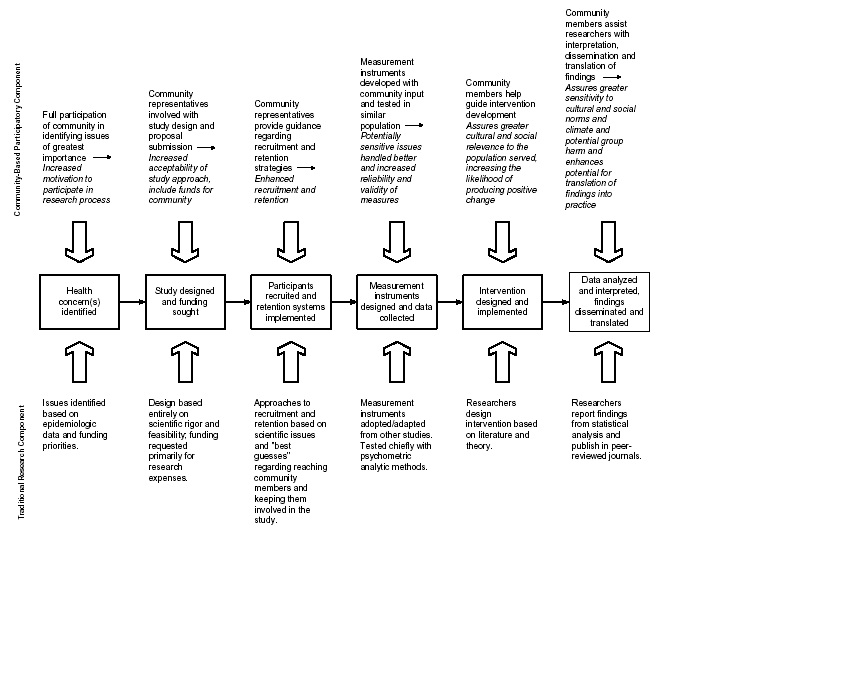

Figure 1

Source: National Library of Medicine/AHRQ-Evidence Report 2005

CBPR expands the potential for transforming research findings into practice and application—commonly known as translational sciences to develop, implement and dissemination effective interventions across diverse communities through strategies designed to reduce power imbalances, facilitate mutual benefit among community and academic partners as well as promote reciprocal knowledge translation thereby incorporating community theories into research design.

These approaches have not always served us well. Indeed there is ample evidence of disrespect for example - Tuskegee, as well as inappropriateness, in design and conduct for example - HIV/AIDS Investigations in South Africa. In countries where there are rudimentary or non-extinct research protection process to such as institutional review board (IRB) or patient's bill of rights, and where informed consent is not adequately enforced abuses are prone to occur.

There is increased interest in research that aims to improve the health of disadvantaged (low income) populations. However, conventional research in these communities has a contentious history and offers limited opportunities to improve the health and well being of these communities.

Participatory research in disadvantaged communities has a long and successful history in the social sciences and international and rural development. There is a growing recognition of the importance and promise of this type of research within health services and public health institutions and funding organizations. However, in spite of the increased interest expressed by communities, universities, and funders, CBPR is underutilized primarily as it is mistaken, perceived as lacking essential features of traditional scientific method namely - scientific rigour.

Community-based research processes differ fundamentally from mainstream research in the following ways:

There is significant demand for community-based research, however the need is not being met here in Anguilla and elsewhere. Every organization we consulted attests to the need for more community-based research as they understand it.

Most Anguillan community centres/groups find their ability to conduct CBPR is chronically constrained by an inadequate funding base. Although some agencies are impacted more acutely than others, more than half the centres' personnel we talked to worry that lack of funding could force them to shut down.

Traditional research projects in academia, industry, and government often cost from $50,000 up to $1 million, and occasionally much more. In comparison, community-based research is cost-effective. A typical community research project in Anguilla can cost approximately US$15,000, and can be effective in addressing important social problems, by having data on the issues that affect individuals in the community, empowers and provides other tangible benefits to groups that are often among society's least advantaged, produces secondary social benefits (such as enhancing participating students' education-for-citizenship), and produces little or no unintended social or environmental harm.

Amongst the long term goals of Anguilla Community College is the establishment of a comprehensive community research system that can address questions on virtually any topic for any group or organization throughout Anguillan civil society located anywhere on the Island.

Later a regional Institute's Community Research Network (CRN) initiative can be sought to establish similar capabilities including organizing a national planning conference, creating a regional Internet discussion forum for community-based research, publishing a monograph, as well as designing a searchable Internet database of community research centres in the region.

Of course the underlying rationale for wanting some type of regional/national collaboration is to conduct research that is in the social interest but that the conventional research system will not fund or is ill-prepared to conduct.

Collaboration with grassroots and other non-expert groups is one of the defining characteristics of community-based research. The mutually respectful relationship that needs to exist between experts and other community member's takes time to build. For example, tensions constantly arise in trying to reconcile university timetables and pacing with the sense of urgency pervasive among community organizations. Community research centre staff creates environments supporting successful collaboration by developing sensitivity to the areas where tension arises and skills in nurturing and mediating partnerships.

Participatory Research - We see the Community College of Anguilla through its community research centre conducting more participatory research. "Participatory research" aspires to involve community members in all stages of the research process. From a societal or community research centre's point of view, there is a significant economic benefit in involving our students: they can be rewarded partially or entirely with academic credit rather than monetarily.

Linkages/Collaboration. There are differing strengths and drawbacks to community research centres that are based in colleges/universities versus those that are independent nonprofit organizations. For example, some groups may feel that a college/university affiliation enhances their stature in the eyes of potential funders, provided overhead support, or eased recruitment of student interns. Potential drawbacks, however, include the possible requirement to pay high overhead charges on research grants or becoming subject to inhibiting laws or regulations (e.g. Human Subjects Review Committee procedures that were never designed with participatory, community-based research in mind). (Anguilla does not have any guidelines or policy in place for the protection of Human Subjects.)

Many of the lead informants in Community Organization are people who when interviewed knowing that it will be recorded and documented are often reluctant to share their organizations' negative experiences. For example, when asked about tensions that may arise between community members and experts while conducting research often they outright deny or play down conflict experienced in working together and often reply with the lines: "We get on fine!" The question then becomes how do we as researchers interpret such remarks?

Role of opinion leaders - researchers must be mindful of the need to select opinion leaders from a wide cross section of the population are not those with loud voices thereby reducing bias in the selection of information gathered and reported.

Aside from limitations in our individual case studies, there are further limitations associated with issues of overall sampling and the criteria involved in selecting particular organization for a case study. Thus, although we often want to select project illustrating how community-based research has been used to support social change we are constrained as to the extent that we can generalize our findings.

Examples

A roundtable to examine the scientific method of coordinating environmental health research and other methods to observe health effects in various communities. Some topics that will be addressed by the presenters are as follows: Healthy public housing initiatives; social and environmental determinants of hypertension in Anguillians; eliminating health disparities through community-based research, training, and outreach; lessons learned from a community outreach study in the populations; determining health risks from toxic waste sites.

Learning Objectives: At the conclusion of the session, the participant (learner) in this session will be able to: articulate the process of implementing a multi-stakeholder community based participatory research infrastructure and project in a unique setting; identify at least 3 ways community members can be directly involved in the design and implementation of an environmental health study; discuss the need to have a dynamic organizational structure capable of responding to inevitable challenges that are present in complex community-based projects; articulate procedures for assessing exposure to chemicals within cultural context; identify the failures and successes of community based research on the environmental determinants of hypertension, and health disparities in the populations; discuss issues related to conducting health effects and intervention/education research in the Anguillian population; describe the evidence linking lead exposure and stress with disparities in hypertension in Anguillians.

Moderator(s): Kacee Deener, MPH

| 1 | Determining Health Risks from Toxic Waste: An Integrative Bio-Psychosocial Approach Robert Wright, MD, Rosalind Wright, MD, Rebecca Jim, Earl Hatley, Mark Osborn, MD, Adrienne Ettinger, ScD, Karen E. Peterson, RD, DSc, James Shine, PhD, Jonathon Hook, Howard Hu, MD ScD |

| 2 | Healthy Public Housing Initiative: A city, tenant and academic collaborative John Spengler, PhD, Jonathan Levy, ScD, H. Patricia Hynes, MS, MA, Doug Brugge, Kate Bennett, Margaret Reid, Laura Bradeen, Mae Bradley, Kim Vermeer, John Snell |

| 3 | Social and environmental determinants of hypertension in African Americans: Project CHOICE in the rural community of Gadsden County Florida Richard D. Gragg, PhD, Cynthia M. Harris, PhD, DABT, Cynthia H. Harris, PhD, Saleh M. M. Rahman, MBBS, PhD, MPH, Selina Rahman, MBBS, PhD, MPH, Angela Burgess |

| 4 | Community participation in the study design and implementation of a health and exposure effects study: Community Action Against Asthma Thomas Robins, Wilma Brakefield-Caldwell, BSN, Katherine Edgren, MSW, Barbara Israel, DrPH, Toby Lewis, MD, Edith Parker, DrPH, Paul Max, Sonya Grant Pierson, MSW, Maria Salinas, Donele Wilkins, J. Timothy Dvonch, PhD |

| 5 | A partnership approach to disseminating results of a combined health and exposure effects and intervention study: Community Action Against Asthma Edith Parker, DrPH, Wilma Brakefield-Caldwell, BSN, Katherine Edgren, MSW, Yolanda Hill, MSW, Barbara Israel, DrPH, Toby Lewis, MD, Paul Max, Sonya Grant Pierson, MSW, Thomas Robins, Zachary Rowe, Maria Salinas, Donele Wilkins, J. Timothy Dvonch, PhD |

| 6 | Conceptual model for eliminating health disparities through community based research, training and outreach in urban and rural settings: Project CHOICE Saleh M. M. Rahman, MBBS, PhD, MPH, Richard D. Gragg, PhD, Brian K. Gibbs, PhD, Cynthia M. Harris, PhD, DABT, Cynthia H. Harris, PhD, Howard Hu, MD ScD, Deborah Prothrow-Stith, MD |

| 7 | Lessons from conducting community-based research in a Southeast Asian immigrant population Susan Schantz, PhD, Anne Sweeney, PhD, Vicky Persky, MD, Jennifer Peck, PhD, Donna Gasior, MS |

| 8 | Social and Environmental Determinants of Hypertension in African-Americans: Project CHOICE in the Urban Community of Roxbury, Boston Brian K. Gibbs, PhD, Genita Johnson, Junenette Peters, ScD, Deborah Prothrow-Stith, MD, Eileen McNeely, PhD, Nancy Krieger, PhD, Howard Hu, MD ScD |

Examples from the US

Group-based stress Management and relaxation training for HIV and women significantly -

Our CBPR approach allows us to include relevant stakeholders in:

This encourages

Example of CBPR to be launched by Anguilla Community College

Shape-up Anguilla - Obesity Prevention

EAT SMART, PLAY HARD is a campaign to increase daily physical ability and healthy eating through programming, physical infrastructure improvements and policy work.

This campaign will target schools, government departments, private sector workplaces, civil organizations and community groups.

The study will employ and implement strategies designed to create energy balance for elementary school children. These strategies will be employed in a before, during and after school environments and focused on improving dietary choices and on increasing the number of physical activity options available to children throughout the day.

Through

Significant Improvements in

CBPR - focusing on Community strengths and issues and engages the community in the research process.

The ultimate goal of CBPR is the integration of science and practice.

Limitations

On the other hand we must be mindful of the inherent limitations that CBPR faces due often to resource constraints, but also methodological overreliance on the case study method. Often case studies are based almost entirely on information provided by the organizations being investigated. Thus in most (but not all) cases we were not able to take into account the perspectives of outside evaluators; of community constituents with whom these organizations had collaborated; or of any additional organizations involved in multi-institutional, community-based research partnerships.

CBPR PROVIDES A MUCH NEEDED MECHANISM where the needs of countless communities across the Island and the region can be addressed. By expanding the social infrastructure for conducting community-based research, thereby making empowerment-through-mutual-learning universally accessible, we can better direct the island's capabilities toward its social and environmental needs. We can help alleviate suffering, revitalize democracy and community life, and bequeath future generations a world better than we found it.

Many community researchers challenge the conventional distinction between "laypeople" and "experts," which tends to denigrate lay knowledge and expertise. Thus, some adopt alternative distinctions, such as "no credentialed experts" versus "credentialed experts."

Averill J. Community partnership through a nursing lens. In: Minkler M., Wallerstein N., eds. Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008:431-434.

Becker A.B., Israel B.A., Allen A.J. Strategies and techniques for effective group process in CBPR partnerships. In: Israel B.A., Eng E., Schulz A.J., Parker E.A., eds. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005:52-72.

Bell J., Standish M. Communities and health policy: a pathway for change. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):339-342.

Buchanan D.R., Miller F.G., Wallerstein N. Ethical issues in community-based participatory research: balancing rigorous research with community participation in community intervention studies. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2007;1(2): 153-160.

Calleson D., Siefer S.D., Maurana C. Forces affecting community involvement of Academic Health Centers: perspectives of institutional and faculty leaders. Acad Med. 2002;77(1):72-81.

Cargo M., Mercer S.L. The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:325-350.

Cashman S.B., Adeky S., Allen A.J. III., et al. The power and the promise: working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1407-1417.

Chávez V., Duran B., Baker Q., Avila M.M., Wallerstein N. The dance of race and privilege in CBPR. In: Minkler M., Wallerstein N., eds. Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008:91-105.

Guenther K.M. The politics of names: rethinking the methodological and ethical significance of naming people, organizations, and places. Qual Res. 2009; 9(4):411-421.

Gutierrez L.M., Lewis E.A. Education, participation, and capacity building in community organizing with women of color. In: Minkler M., ed. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. 2nd ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2005:240-253.

Irwin A. The politics of talk: coming to terms with the "new" scientific governance. Soc Stud Sci. 2006;36:299-320.

Israel B.A., Eng E., Schulz A.J., Parker E.A. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005.

Israel B., Schulz A., Parker E., Becker A., Allen A., Guzman J.R. Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles. In: Minkler M., Wallerstein N., eds. Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008: 47-66.

Israel B.A., Schulz A.J., Parker E.A., Becker A.B. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998; 19:173-202.

Jones L., Koegel P., Wells K.B. Bringing experimental design to community-partnered participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008:67-85.

Jones L., Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407-410.

Lopez-Viets V., Baca C., Venner K., Verney S., Parker T., Wallerstein N. Reducing health disparities through a culturally centered mentorship program for minority faculty: the Southwest Addictions Research Group (SARG) Experience. Acad Med. 2009:84(8):1118-1126.

Mercer S.L., Green L.W., Cargo M., et al. Reliability-tested guidelines for assessing participatory research projects. In: Minkler M., Wallerstein N., eds. Community Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008: 407-418.

Miller R.L., Shinn M. Learning from communities: overcoming difficulties in dissemination of prevention and promotion efforts. Am J Community Psychol. 2005;35(3-4):169-183.

Minkler M., Vásquez V.B., Chang C., et al. Promoting Healthy Public Policy Through Community-Based Participatory Research: Ten Case Studies. Oakland, CA: Policy Link; 2008.

Morone J.A., Kilbreth E.H. Power to the people? Restoring citizen participation. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2003; 28(2-3):271-288.

Seifer S.D. Making the best case for community-engaged scholarship in promotion and tenure review. In: Minkler M., Wallerstein N., eds. Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008:425-430.

Syme S.L. Social determinants of health: the community as an empowered partner. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1(1):1-8.

Wallerstein N.B., Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312-323.

Wallerstein N., Duran B., Minkler M., Foley K. Developing and maintaining partnerships with Communities. In: Israel B., Eng E., Schulz A., Parker E., eds. Methods in Community Based Participatory Research Methods. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005:31-51.

Wallerstein, N. et al. (2010) Community-based Participatory Research Contributions to Intervention Research The Intersection of science and practice to Improve Health Equity. Amer. J Public Health 2010 S40-S46.

Westfall J., VanVorst R.F., Main D.S., Hebert C. Community-based participatory research in practice-based research networks. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(1):8-14.

© Professor Delroy M. Louden & Susan Hodge

HTML last revised 29th April, 2012.

Return to Conference papers.