Map of the Antilles (click on image to see larger version)

"We find some difficulty to know ourselves, so different are we grown from what we were here-to-fore..." Kalinago man to M. du Montel 1665 (Davies 1666:250).

"What is to happen to the poor Carib. Is he to go and live in the sea with the fish?" Kalinago man to Fr. Beaumont 1660.

As colonizing forces advanced across the Grenadian landscape in the 17th century, the indigenous Kalinago people were routed. Past histories have focused on the human and physical loss occasioned by the genocide. But this paper focuses on the loss of the indigenous cosmology, their perception of their place within the environment of this island world. It shows how the process of contact and cultural exchange had begun years earlier and that by the time a group of Kalinago jumped to their deaths over the cliff at Sauteurs in northern Grenada, their world had been turned upside down. Their culturally structured place within the cosmic and ecological pattern of this archipelago had disappeared and their lives no longer made any sense within it. Since then, the Kalinago perception of the Grenadian environment, and its people's place within the cycles of this tropical oceanic island, has been wiped out. An alien vision of this environment has been imposed over the period of the past four hundred years. This paper explains the Kalinago concepts of their island, Kamahone (Grenada). It studies the island's relationship with the continent to the south and discusses its role as the indigenous gateway from the mainland to the islands. It shows how relevant the indigenous concepts of the environment still are today. It argues that elements of this cosmology need to be regained and more widely understood if we are to come to terms with the balance needed in the human ecology of neo-colonial Grenada.

For the indigenous explorers who set out from Lowland South America some five thousand years ago, the island of Grenada, known to its last Kalinago (Carib) inhabitants as Camaghone (Kamahone) (Breton 1665) was the gateway to a new world of volcanic islands. Trinidad and Tobago were continental, but Grenada was the first oceanic island of the chain, born from the seabed in a series of violent eruptions.

Distinct styles of pottery, divided into successive ceramic series extending along the island chain from the mouth of the Orinoco River, have formed the basis of theories on regional systems and chronological frontiers of settlement and culture. Following the course of the South Equatorial Current as it curved up into the Caribbean, and aided by the close proximity of the islands to one another along the chain, various groups of mainland people moved from the Orinoco delta northwards. How these groups integrated or succeeded each other has been a hotly debated issue in Caribbean archaeology. Wilson (1994) represents the most recent view that historical and archaeological evidence from the Lesser Antilles suggests that there was more cultural heterogeneity than had previously been recognized:

Although speculative, I feel it is more likely that the prehistoric and early historic Lesser Antilles contained a complex mosaic of ethnic groups which had considerable interaction with each other, the mainland and the Greater Antilles. As now, the individual islands and island groups would have become populous Trading centres or isolated backwaters according to the abundance of their resources, the strength of their social and political ties with other centres, and their unique histories of colonisation and cultural change (Wilson 1994).

That there was a 'complex mosaic' composed of popular trading centres and isolated backwaters at the time of this immigration is supported by Allaire (1977). "Warlike Caribs" wiping out "peaceful Arawaks" is an outdated theory. Trading, raiding, intermixture between groups and a transfer of knowledge across the islands and to and from the mainland between all groups is now accepted. As Grenada's richly varied archaeology has shown, the island was in the midst of this moving mosaic of Amerindian culture. The Kalinago people (called Caribs by the Europeans) were inheritors of what had gone before.

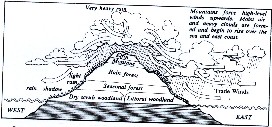

The study of Amerindian interaction with their specific island environments along the chain of the Caribbean archipelago are enmeshed within the human ecology of the indigenous people before and after contact with Europeans. Kalinago life was linked to the geology, climate patterns, vegetation and maritime features that influenced the ways in which the islands' natural environment was utilised (Krasniewicz 1978). Comparative studies of such practices as ethnobotany, sources of raw materials for tools and other technology, knowledge of hunting and gathering areas, fishing grounds, routes of navigation and mythical geography are dependent on a comprehensive understanding of the geology, geophysics and natural history of the island. Such an exercise requires us first to revisualise the region, stripping it to a purely geographical entity, seeing it from the perspective of the cultural interaction of a horticultural and hunter-gatherer people and the human ecology of their survival within the natural environment of these oceanic islands.

The Lesser Antilles is made up of two volcanic island arcs adjacent to one another. The outer arc, lying to the east, is older, having been formed in the pre-Miocene. Because of their age, the islands of this arc are more severely eroded and their peaks have been worn down to less than 1,000 feet above sea level. Coral reefs have developed upon the coastal remnants and the accumulated sediment, creating white coral sand beaches. These older islands of the Lesser Antilles are: The Virgin Islands, Anguilla, St. Martin, St. Barthelemy, Barbuda, Antigua, the eastern wing of Guadeloupe and the island of Marie Galante. Some islands to the south are composed of a combination of the two geological periods. Evidence of the older arc appears in the southern part of Martinique, the northern coast and southern tip of St. Lucia, the islands of the Grenadines and the southern tip of Grenada (Multer et al. 1986).

Map of the Antilles (click on image to see larger version)

The inner, younger arc, is characterised by islands or parts of islands, with high volcanic peaks rising to almost 5,000 feet above sea level, rugged, sharply falling coastlines, black sand beaches and the remnants of volcanic activity in the form of sulphur springs, boiling craters and intermittently active volcanoes. There is evidence that pre-Columbian settlements have been affected by volcanic eruptions at various times and were in some cases entirely covered by ash and pyroclastic flows (Allaire 1989). This inner arc was formed in the later Miocene and Pliocene and comprises: northern Grenada, St. Vincent, central St. Lucia, northern Martinique, all of Dominica, western Guadeloupe and all of Montserrat, Redonda, Nevis, St. Kitts, St. Eustatius and Saba (Martin-Kay 1971: Vol.10:172). The combination of features of two major periods of geological activity at different parts of the same island, as in the case of Grenada, St. Lucia, Martinique and Guadeloupe, resulted in markedly different ecological areas within those islands. With human occupation, these zones were utilised in contrasting ways according to the resources which they provided.

The cosmology of the Kalinago, their perception and understanding of the world they lived in, had been inherited from generations of islanders before them. It had been transferred through tribal elders in story and song, by instruction and ceremony so that it gave them order to the chaos of the world. It was aimed at achieving balance between good and evil. It anchored the society in a symbiotic relationship with nature. It gave structure to their lives. This relationship was based on observation and a deep knowledge of their environment. The Amerindian in the islands was an integral part of the natural cycle, and the spirits which held it all in place had to be understood and placated. Without this, the people's access to, and use of, the natural resources available for gathering, hunting and horticulture would be greatly hindered.

The move to the islands meant a cultural transformation from a continental world to that of an island world. The geophysical structure of the islands determined a very different flora, fauna and marine ecology from what existed along the rivers and coastline of the continent. The cosmology had to change as well.

It was not only the techniques and resources of hunting, gathering and horticulture, which had to be restructured. The main characters that made up their mythology had to be transformed. There were no jaguars, tapirs or anacondas here and so the protagonists of the island mythology gradually took on the guise of bat, frog, gecko, owl and boa constrictor. These were important inn placing men and women's roles into the orderly cycle of life's work and the group's survival.

For the Lesser Antilles, the umbilical cord to the mainland was the Orinoco delta region and the river that rises in the hinterland beyond it. The river and its tributaries had been the primary means of communication for the pre-Columbian settlers of the Caribbean. Their river and forest cultures had long existed within a cosmology tied together by mythologically encoded perceptions of rivers, water currents, canoes and star lore (de Civrieux 1980; Wilbert 1993; Taylor 1946a). To give an example, the landmass of South America had previously extended much further north than at present and included all of the island of Trinidad. This geographical condition existed until 6,000 years ago, when the Caribbean Sea was at a lower level (Nicholson 1976:4/2; Hodell et al. 1991). Significantly this geophysical phenomenon remains registered within the mythic geography of the Warao who now live on the Orinoco delta. Their oral history, encoded in creation myths, speaks of a time when the Serpent's Mouth was dry and Trinidad was connected to the mainland (Wilbert 1993:7). The ancestral memory of a period so remote does suggest the remarkable resilience of tribal history contained in myth.

The most definitive element of the landscape that represented Grenada and the islands to the north for the indigenous groups was the volcanic peak. So unusual were these high summits to the people of the delta region that in the mythology of the Warao, Naparima Hill in southern Trinidad was considered to be a pillar holding up the sky on the edge of the Warao world (Wilbert 1993).

Coming from the flat river banks and delta region it was the volcanic peaks, rising out of the sea in a gently curving arc along their route northwards which became the main symbol in their mythic geography once they reached the islands. These peaks gave the islands life and they were the source of all the natural resources that the islands contained. The image of the volcano became the centrepiece for the cosmology of the successive waves of island-based tribes that followed the first agricultural and pottery making people now known as the Saladoid. From their arrival in the islands at the beginning of the Christian era, the volcano was represented in shell, stone and clay in the form of a religious object called a zemi. Because these particular zemies are cut, carved or moulded into the shape of the triangle of a volcanic peak, they are called "three-pointers".

The Saladoid had found a natural object with which to make these first "three-pointer" zemis of the volcano. In the waters around these islands lives the distinctive Strombus gigas or conch and its shell provided an image not just of single volcanic peaks as determined by Olsen (1974) but if studied carefully, the entire shell provides a rough three-dimensional map of the volcanic island cones of the Lesser Antilles. Not only have individual pieces of the points on the conch shell been found to have been cut off from the main shell and carved, but even when these are reproduced in stone or clay they are given a concave base which replicates the concave indentation underneath every conical peak on the conch shell. With the peaks on the conch representing the peaks of the islands then the giant opening of the mouth of the conch may have been interpreted as the bocas of the Orinoco River from which successive groups of indigenous islanders had come.

Various zemis (click on image to see larger version)

Once on the islands, these people were well aware of the power of the volcano. Saladoid sites in Dominica and Martinique have been found covered in volcanic ash. They would have witnessed the periodic swarms of tremors, earthquakes and the eruptions themselves. Along the chain there were fumeroles and smouldering craters and crater lakes as here in Grenada. In Kalinago myth, which was handed down through other previous occupants of the islands, there was a time when all the land was hot and soft and rose out of the sea (Taylor 1952). Animals came upon these soft islands led by the island version of the South American anaconda in the form of Antillean boa constrictors. These arrival points were geological features called dykes, where volcanic forces have split the bedrock forcing the lava through the crack horizontally.

The three-pointer volcano zemis represented the spirit that gave fertility to the land. It made things grow, it brought rain just as the mountain peaks caused rain to fall. It balanced the dry season with the wet. It was in effect the whole bounty of the island. Small zemis of this type were buried in fields to make crops grow, larger ones of stone were carved with the earth spirit at their base holding the volcano on the back. "The earth was an indulgent mother who furnished them with all things necessary to life" (Davies: 1666:277). "Our gods have made our country and cause our manioc to grow", the Kalinago told Christian missionaries. To the zemis they make offerings of cassava and their first fruit (Davies: 1666:278-79).

There was an awareness of the variation of geological resources on different parts of the island and across the island chain. Specific geological areas for obtaining the types of stone needed for a variety of uses were mapped in the Kalinago mind. Flakes of jasper, for instance were necessary for making graters, takia kani, for shredding cassava tubers. The identification of jasper deposits on each island was crucial for this process as were types of rock best suited for making into particular tools and other objects. Some of these are recorded by Breton with their Kalinago names and are identified in some cases to have been common to particular islands (Breton 1665:195):

tebou - stone

couléhueyou - firestone, for lighting fire

coyébali itágueli - smooth stone

taoüa - white stone

coyláya - black stone

ouroúali - pumice stone, with which they polish their 'auirons'

cherouli - pumice stone from Marie Galante

méoulou - pumice stone from Martinique

teukê oúbao - precious stones

tlimáparacola balou balou - green stone for the men

tácaoüa, tacoúlaoüa - green stones which serve as jewels for the women

macónabou - counterfeit green stones (Breton 1665:291, 292).

Extending these parameters even further afield, there is evidence of goods being traded along the islands from as far as South America and northwards to Puerto Rico (Rodriguez 1991; Cody 1991) that compliments the archaeological work done by Boomert (1987) on trading "green stones" from the Amazon along the Guiana coast and through the archipelago. The French missionaries report that green stones were still an important trade good from the mainland even while the French and English were beginning colonisation (Du Tertre 1667: Vol.II:VII:I:385).

Marine resources which were prolific on low, coral-encrusted islands would have been complimented by forest resources and volcanic rock materials available on adjacent mountainous islands. In considering the exploitation of these zones and the relationships which were stimulated by this activity among groups inhabiting the islands, one is led to assess the likelihood of continuous inter-island movement of people and goods.

Ethnohistorical and oral information on the ethnobotany of the Kalinago further informs the search for surviving areas of natural vegetation where such resources would have been available or are still in existence (Multer et al. 1986). Seasonal migrations, trade routes and inter-island patterns of fishing and gathering would have been developed according to the location of such resources (Wing 1968; Wing & Reitz 1983).

In Grenada as with the rest of the Windward Islands, several varied faunal habitats and vegetation zones were juxtaposed within close proximity to each other as a result of geophysical and micro-climatic diversity. These ecological micro-zones were observed with interest by the early French settlers: "what is remarkable in these isles, and it is very curious to observe, is the points of the fauna's habitation: a zone for frigates, for grand gosiers, for mauves, for iguanas, anoli [lizards], soldier crabs, white crabs, purple crabs" (Du Tertre 1667: Vol.II:I:15). Davies reports that the inhabitants of Grenada had good fishing and hunting "in and about the islands called the Grenadines lying north east from it" (Davies 1666:7). The Kalinago of the northern Windward Islands went as far as the beaches of Tobago to hunt for turtles and manatees (Davies 1666:7).

Cross section of the island showing different vegetation zones and thereby different levels of natural resources used by indigenous people for housing, canoes, medicine, consumption, farming, basket making, etc. (click on image to see larger version)

Horticulture had to be even more carefully controlled and understood than hunting and gathering for food and materials for tools. Knowledge of the seasonal changes on this tropical island was crucial and it was also anchored by myth. Every year planet Earth goes through its seasonal cycles as it tilts backwards and forwards in its continuous journey around the sun. For thousands of years, all over the planet, groups of human beings have patterned their lives and their beliefs on this cycle of the seasons. Agricultural people, herders of livestock, hunters and gatherers all created religions to give order to their lives and to explain the world around them and their place within it. Most of their religious festivals were, or still are, based on these seasonal changes and apparent movements of the sun. Winter, spring, summer and autumn are the marked seasons of the temperate regions of the northern and southern hemisphere. When colonizers arrived in the Caribbean from Western Europe, they brought their own seasonal and religious perception of the temperate, Christianized world with them. As the conquerors, this "world view" was omnipotent and it was superimposed upon the tropical environment and the people who were found here.

But for those descendants of tribes who had inhabited the islands of the Caribbean for some 4,500 years previously, there was another perception of reality, another "world view". It was based on the accumulated ancestral knowledge of a tropical island world. Here in the Caribbean, the main annual changes are marked by the wet season and the dry season.

The Kalinago people, like their other Amerindian ancestors who lived on the islands before them, divided the year into these two seasons. One half of the year was male, the other half was female. The male was dry. The Female was wet. The men were represented by the image of the bat and the women by the image of the frog. The dry season was the time of the Bat Man. The wet season was the time of the Frog Woman. The time of the Bat Man begins on December 21 when the sun appears to be at its furthest point south, while the time of the Frog Woman begins on 21 June when the sun appears to be at its furthest point north.

Up and down the Antilles from Grenada to the Greater Antilles, images of the bat and frog are found in pre-columbian archaeology. They are carved on rocks in the form of petroglyphs, they appear on decorated pottery and are crafted into shell amulets used as jewelry. To keep track of the movement of the earth in relation to the sun, natural and manmade markers helped the Kalinago, and those before them, to observe the change in its position. When carved as petroglyphs they often face east or west towards the rising or setting sun. Examples can be seen at Caguana ball courts in central Puerto Rico, in St. Kitts, Guadeloupe and Grenada.

When considering the Bat Man who represents the dry season, one may well point out that December, January and February are not dry months. But they are leading up towards it. Halfway through the time of the Bat Man, the sun is over the equator and then over the Lesser Antilles causing the climax of the dry season to set in. So from December 21, the Bat Man warns us to get prepared for the dry season. It is time to select land in the forest for new gardens and time to cut clearings, so that at the height of the dry season the men can burn the fallen wood. It is time to cut trees for canoes and house posts watching also the right phases of the moon, for moon cycles must be followed within the cycles of the sun.

The bat likes to be dry, he goes out hunting and then comes back to his shelter.

Men mostly spend their time abroad, but their wives keep at home and do all that is required around the house. The men fell timber for the houses and keep them in repair... men go hunting and fishing, women prepare the food (Davies 1666:294)

Bat Man and Frog Woman (click on image to see larger version)

By June 21, the Summer Solstice, the dry season is coming to an end, the fields are ready and on that day we enter the time of the Frog Woman. The wet season is beginning. Frogs come out when it rains. They produce many eggs. The Frog woman represents fertility. She is always depicted in stone, shell and clay as half frog, half woman: her hands and feet are webbed; she faces us with her arms and legs splayed apart like the limbs of a squatting frog. Her navel is prominent at the centre of every image made of her. Her vagina is exposed. She is ready for sex. The Amerindians were frank about such things before the influences of colonization introduced the concepts of shame, cover up and sexual hypocrisy.

The Frog woman was fertile and her time, from June 21 to December 21, was the time to plant. The rain is falling, the soil is rich with moisture. During the dry season the men had done their work and now, in tune with the cycle of the seasons it was the turn of the women to plant. Under the spirit of the Frog Woman that was their task, for only through their hands would the slips of cassava, yam, tannia and sweet potatoes prosper of the peas and corn bear fruit.

Women take care of everything for the subsistence of the family... Women get in the manioc, prepare the Cassava and Ouicou, dress all the meat... set the gardens, keep the house clean... paint their husbands [with roucou, annatto, bixia] spin cotton. Their work is never at an end... so they are rather to be accounted slaves than companions (Davies 1666:294).

As the sun was seen to pass south over the equator once more, halfway through the time of the Frog Woman, it was the peak time (in modern day mid September) for the fearful spirit Huracan to make his appearance. With powerful winds he tears the forests to shreds, destroys houses and raises ocean waves. The women had to have their plants safely under the ground by the time that the sun had marked its halfway path over the equator, for this marked the time of Huracan's most powerful wrath. The Kalinago festivals of December 21, at the end of the time of the Frog Woman also celebrated the end of the season of Houracan.

Integrated into these cycles of the sun, were the phases of the moon. The movement of stars were also linked with seasonal movements of wildlife. Each Kalinago constellation had its own story to explain its place in the sky. The shift of the north-east winds during the year. The movements of pelagic fish and the use of herbs from different levels of the island's vegetational zones all formed part of this wider cycle of natural events. The destruction of the Kalinago meant the eradication of this knowledge from the face of the island. Those who took over had to start from scratch, and to a large extent they were unable to retrieve the balance.

Quoting a French settler's conversation with two Caribs who were "considering the degradation of their countrymen", Rochefort records one of the Carib's statements which concisely sums up the psychological state of their people at the middle of the seventeenth century. It could also have been spoken by an enslaved African or an East Indian indentured servant in the centuries which followed, for it expresses the psychosis of colonisation and the process of creolisation:

Our people are becoming in a manner like yours, since they came to be acquainted with you; and we find it some difficulty to know ourselves, so different are we grown from what we were here-to-fore (Davies 1666:250).

For modern Grenada, the ultimate defiance, when a group of Kalinago leaped off of the cliff at Sauteurs has become a symbol of heroism, a legend of nationalism and yet another local story with which to embellish the "tourism product". A French historian of the Caribbean writes that "The episode of Morne des Sauteurs, or as the English call it, Caribs Leap, is material for the as yet unwritten epic poetry of the Caribbean." (Roberts: 1971:55) He, like many others, makes the mistake of saying that the very last of the Kalinagos on Grenada jumped off that cliff. But others survived to carry on the fight in other parts of the east coast. Even some 350 years ago the French priest and writer Du Tertre ticks off another Frenchman Rochefort, for being similarly ill informed on the capture of Grenada.

Contact and culture exchange in both trade and war between Europeans and the Kalinago was in progress long before the first permanent settlement was established on Grenada by Du Parquet in 1650. As in the days before Columbus, the island had been in the centre of the route between the islands and the mainland and the Kalinago of Grenada were already fighting off the threat of the European advance into their territory. A combination of trade and armed resistance had been the most obvious Kalinago approach to Europeans from the time of first contact.

The earliest impact on the Kalinago of Grenada was slave raiding. On 30 October 1503, the Queen of Spain was persuaded to issue an order proscribing capture or injury for any Indians, whether living on the islands or the mainland, but making an exception of "a certain people called Cannibals" who could be captured and enslaved (Sauer 1966:161). More specific orders were given in the cedula of 23 December 1511 which granted Spanish colonists the right to capture and enslave Kalinagos on:

The Islands and Mainland of the Ocean Sea discovered up to now, as well as to any other Islands that may be discovered, to make war on the Caribs of the Island of Trynidad, Varis, and Domynica, and Mantenino, and Sancta Lucia, and Sant Vincente and Concebcion, and Barbudos, and Cabaco and Mayo (from a translation by Harriet de Onis, appearing in Jesse 1963:23.)

There were other edicts issued on 7 November 1508 and 3 July 1512 granting similar liberties against the Kalinagos (Beckles 1992:1). They justified this action because of the Kalinagos "resistance to Christians" and for "making war on the Indians who are in Our service, and taking them prisoners, they eat them, as they really do" (Jesse 1963:27). Together these cedulas gave permission to wage war upon, enslave and sell duty-free any Kalinagos on these islands and were aimed not only at providing slaves but at the same time clearing the islands of dangerous neighbours.

For years during the Spanish settlement of Puerto Rico the Kalinagos harassed the east and south coasts of that island in order to prevent further expansion southwards into the Virgin Islands. In the southern islands in 1569, 300 Kalinagos from Grenada in 14 canoes were attacking Spanish settlements along the Venezuelan coast near Carabelleda (Oviedo Y Banos 1987:210). In the Orinoco region Kalinagos from Dominica also attacked Spanish colonising parties as they moved along the Guarapiche River from Trinidad (Whitehead 1988:83). On islands such as Grenada the ethnographers were given accounts of the alliances with "the Galibis of the Guyanas or the Savage Coast" with which the Kalinagos would join forces in their attacks (Davies 1666:207). Together, these raids on Puerto Rico, the Guianas and Venezuela, show the extent of the Kalinagos' three-pronged offensive against encroachment into the islands and the alliances that existed with tribes in those regions on the islands and Tierra Firme. They even fell on loaded Spanish vessels in mid-ocean. The warfare they practised was swift and fierce and initial efforts to control the Kalinago assaults proved useless. The continuous and determined movement between South America and the islands, either for hunting, gathering, trade, war, or retreat from Spanish slave raiding, was recorded well into the seventeenth century (Breton 1665:379; Davies 1666:7; Du Tertre 1667: Vol.II:VII:I:385) and it was to confound the Europeans during the period of indigenous resistance.

On 1 April 1609, three shiploads of English settlers arrived in Grenada but were attacked by Kalinagos as soon as they disembarked. Within a few months the whole undertaking was abandoned but the idea remained that Grenada could be used as a base for trade and attack on Spanish interests in Trinidad and the mainland (Williamson 1926:19). So active was the movement in and around Grenada, it was one of the reasons Thomas Warner rejected it as a place for settlement. It was too close to the Spanish in Trinidad and Venezuela and there was far too much Kalinago traffic passing by between the mainland to and from the northern Windward Islands (Williamson 1926:12). It was against this background of over a century of cultural and physical contention that the net was finally being drawn around the Kalinago control of Grenada.

To understand the preamble to the famous incident at Sauteurs, Du Tertre is in most cases the most reliable informant. The governor of Martinique, Du Parquet, seeking to extend French domination of the Lesser Antilles arrives on Grenada and begins negotiations with Chief Kairouane, bringing the usual gifts of bill hooks, razors, glass, knives, "eau de vie" and other such trade goods. In exchange for this, Du Parquet, with the agreement of the Kalinago in this district, ordered the clearing of land and the commencement of a large plantation where he first directed the growing of food crops, rather than cash crops so as to provide subsistence for the new settlers.

As had happened in the other Windward Islands, there appears to have been a difference of opinion between south-west coast Kalinagos and north-east coast Kalinagos as to the wisdom of inviting colonization. It was one thing to make an agreement to obtain trade goods, but it was quite another to witness the process of colonization as the clearing of land and erection of settlements became visible. In response, the general majority of Kalinago became alarmed and reacted. By then Du Parquet had returned to Martinique and had left his cousin Le Comte in charge of Grenada.

The Kalinagos planned an attack on the French settlement, but Le Comte got news of this in advance and raised a force of 300 men "to take the war to their Carbets and force them to leave the island." In response to this threat, the Kalinago of Grenada sought the help of those in Dominica and St.Vincent to attack the French. The ensuing guerrilla war raged along the coast and across the hills of Grenada. One group of Kalinagos was cornered while making a final stand on the now famous headland at Sauteurs and they leaped over the cliff edge to their deaths rather than surrender.

Anthropological studies of suicide have been profoundly influenced by the French sociologist Emile Durkheim's pioneering study (1897) which distinguishes two types of suicide: the altruistic and the anomic. The latter is characteristic of modern society and is an individual response to situations around one. Altruistic suicide on the other hand, was found to be more common in traditional societies such as the Kalinago. This form of suicide is seen as an expression of commitment to social and cultural norms. When these norms, these long established patterns of living and beliefs are in the process of collapse through defeat in war or natural disaster or unexplained epidemic, a communal sense of hopelessness sets in. Suicide may in these terms be a prescribed or expected response to extreme situations affecting an entire group.

Communal suicide among the native people of the Caribbean in the face of European expansion in the region was not unique to Grenada. It had been practiced over a century before by groups of Taino people on Hispaniola and Cuba during early Spanish settlement of those islands. It is significant, that in line with the practice of altruistic suicide, the Kalinago also practiced euthanasia in the belief, as Rochefort puts it, that by easing the terminally ill into the afterlife with the use of herbal poisons "they did a good work, and rendered them a charitable office, by delivering them out of many inconveniences and troubles which attend old age" (Davies 1666:347).

Kalinago society was one where the world of the here and now and the world of the spirit interwove with each other like the fibres of their basketwork. The shaman or boye practicing his piai and consuming local narcotics travelled out of this world and returned with solutions to the problems of the present. Armed with this perception of continuous life in different zones of reality, the Kalinago were more than a match for Europeans. Western domination relied on the concept that the enslaved person would do everything possible, including forced labour, to continue living regardless of the conditions. Faced with a society that was prepared to die rather than surrender, the colonizers conquered land but found it impossible to control the living people.

Kalinagos not involved in the mass suicide re-amassed in the mountains along the east coast but Le Comte discovered this also and raised another 150 men to continue the war. He embarked on a scorched earth policy to deal with those Kalinago who remained along the Windward coast, burning houses and fields.

What made French victory complete, according to Du Tertre, was that the French found the Kalinago canoes and pirogues in a river mouth and destroyed them, thereby preventing the Kalinagos from escaping or getting help from St.Vincent. Despite his victory, Le Comte died by drowning when the canoe he was riding in overturned. His replacement as governor, De Valminiere, engaged a company of 100 Walloons, previously fighting for the Dutch in Brazil, to defend Grenada against Kalinago assaults. From time to time in the years that followed, Kalinagos attacked outlying French houses and settlements, but the colony was growing quickly and soon the indigenous people gave up their offensives. By the 18th century, those few Kalinagos who survived on the islands had become transformed in the European mind from "warlike cannibals" to romantic remnants of the "noble savage" living on the fringes of colonial plantation society.

Two groups of continental people eventually took over the lands of the Kalinago: the African and the European. Each group arrived under different circumstances, but the societies that they attempted to establish on Grenada were far removed from the Amerindian quest to maintain an integrated balance with the land itself. The dominant religion that one group had brought with them and which was imposed upon the other was Christianity. It came originally from a culture of the desert pastoralists of the Middle East. The Judaic roots of the religion had grown out of a culture, which was tied to a harsh and violently contested land. There man had to control nature in the name of, and with the divine sanction of, a god who placed them above the beasts of the earth. The circumstances of colonialism, slavery, territorial division on land and sea, cash crop plantations and market forces in world trade, left little chance for recreating even the Kalinago perception of Man's place on the islands.

Now and then an earth tremor or the threat of a volcanic eruption reminds the people of the special nature of the islands they inhabit. The globalisation of the world economy is our new colonization. New demands will be made on the land as we trade off pieces so as to keep abreast of economic demands. In an education system with agendas far removed from concepts of its students' place in the natural island world around them, the divorce between a holistic relationship with the land widens. In most of architecture, designs related to breeze, heat and sun have been abandoned. Even the long acquired Creole knowledge of forest trees and wild plants and their uses is disappearing and it is now the preserve of dedicated members of departments such as Forestry and Wildlife and other committed individuals. What was lost at Sauteurs and its aftermath in the mid 17th century was more than a people, it was a human relationship with Grenada, Kamahone that was never to be regained.

Allaire, Louis 1977 - Later prehistory in Martinique and the Island Caribs: problems in ethnic identification. Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University. University Microfilms, Ann Arbor.

Allaire, Louis 1989 - Volcanic chronology and the early Saladoid occupation of Martinique. In Siegel, P.E. (ed.), Early Ceramic Population Lifeways and Adaptive Strategies in the Caribbean, BAR International Series 506, Oxford, pp. 147-168.

Beckles, Hilary M. 1992 - Kalinago (Carib) Resistance to European Colonisation of the Caribbean, Caribbean Quarterly, 38(2&3): 1-14.

Boomert, Arie 1986 - The Cayo Complex of St. Vincent: Ethnohistorical and Archaeological Aspects of the Island Carib Problem, Anthropologica 66: 3-68.

Boomert, Arie 1987 - Gifts of the Amazons: "green stone" pendants and beads as items of ceremonial exchange in Amazonia and the Caribbean, Anthropologica 67: 33-54.

Breton, Raymond 1665 - La Dictionnaire Caräibe-Française, Gilles Bouquet, Auxerre, France.

Cody, Annie 1991 - Distribution of exotic stone artifacts through the Lesser Antilles: Their implications for prehistoric interaction and exchange. Fourteenth IACA, Barbados, pp. 204-226.

Davies, John 1666 - The History of The Charriby Islands, London, (Transl. fr. Charles Rochefort 1665).

de Civrieux, Marc 1978 - Watunna: An Orinoco creation cycle, transl. David Guss, North Point Press, San Fransisco.

Durkheim, Emile 1897 - Suicide (Eng. Trans.), London, 1952.

Du Tertre, Jean-Baptiste 1667 - Histoire generales des Antilles habitees par les Francais, T.Jolly, Paris.

Hodell, D. A., J. H. Curtis, G. A. Jones, et al. 1991 - Reconstruction of Caribbean climate change over the past 10,500 years, Nature 352: 790-793.

Jesse, Rev. C. 1963 - The Spanish Cedula of December 23, 1511 on the subject of the Caribs, Caribbean Quarterly, 9(3).

Krasniewicz, L. 1977 - Prehistoric ethnobotany and West Indian archaeology, Journal of the Virgin Islands Archaeological Society 5: 36-37.

Martin-Kay, P. H. A. 1971 - A summary of the geology of the Lesser Antilles, Overseas Geology and Mineral Resources, 10: 172.

Multer H. G. et al. 1986 - Reefs, Rocks & Highways of History, LISA, Antigua.

Nicholson, Desmond 1976 - Precolumbian seafaring capabilities in the Lesser Antilles, International Congress for the study of Pre-Columbian Cultures in the Lesser Antilles, 1976.

Olsen, Fred 1974 - On the Trail of The Arawaks, Oklahoma University Press.

Oviedo de Y Banos, Don José 1987 - The Conquest and Settlement of Venezuela. Translation and Introduction by Jeannette Johnson Varner, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Roberts, W. Adolphe 1971 - The French in the West Indies, Cooper Square Publications, New York.

Rodriguez, Miguel 1991 - Early trade networks in the Caribbean. Fourteenth IACA, Barbados, pp. 306-314.

Taylor, Douglas M. 1946 - Notes on the star lore of the Caribees, American Anthropologist, 48(2): 215-222, April-June.

Taylor, Douglas M. 1952 - Tales and Legends of the Dominica Caribs, Journal of American Folklore 65 (257): 267-279, July-September.

Sauer, Carl O. 1966 - The Early Spanish Main. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Whitehead, Neil 1988 - Lords of the Tiger Spirit, A history of the Caribs in colonial Venezuela and Guyana 1498-1820, Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-,Land-EnVolkenkunde, Caribbean Series 10. Foris Publ. Dordrecht, Holland.

Wilbert, Johannes 1993 - Mystic Endowment: Religious Ethnography of the Warao Indians, Harvard University Press.

Williamson, James 1926 - Caribbee Islands Under the Proprietary Patents, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Wilson, Samuel M 1994 - The Cultural Mosaic of the Indigenous Caribbean in Europe and America, in The meeting of two worlds: Europe and the Americas 1492-1650, W. Bray (ed.), The British Academy 81: 37-66.

Wing, Elizabeth Schwarz 1968 - Aboriginal fishing in the Windward Islands. Second IACA pp. 103-107. St. Ann's Garrison, Barbados.

Wing, Elizabeth S. and Elizabeth J. Reitz 1983 - Animal Exploitation by Prehistoric People Living on a Tropical Marine Edge. In Animals and Archaeology: 2. Shell Middens, Fishes and Birds, eds. C. Grigson and J. Clutton-Brock, pp. 197-210. Oxford. International Series No. 183.

© Lennox Honychurch, 2002. HTML last revised 19 March 2002.

Return to Conference Papers

.