The town of St. George, Grenada, has been the subject of many studies over many years, due to it unique characteristics such as fish-scale roofs and Georgian architecture. It has also been described for over a century as the most picturesque town in the entire Caribbean. Moreover it is sometimes described as a time capsule as one can trace the development of this town over the last three centuries. Of great interest is the fact that the historic fabric of this town is still in existence, as many structures were either built upon or added to. Likewise many other features, such as old water fountains and wells and old streets or alleys, can still be found hidden within building compounds or simply blocked by brick walls.

Despite the pressures brought on by modern day development, such as the introduction of the motor vehicle and the need for additional space, the town has retained its scale and most of its skyline. As such, the town is still within the boundaries established between 1700 and 1788 with buildings built after the last great fire of 1792. Not only had the town of St. George received special mention from the Georgian Society during the 1930s and 1950s, but also in 1988, it was nominated as one of the monuments of the Wider Caribbean. However, despite its historic attributes, the town has failed to win any award. Therefore, it is the intent of this paper to highlight this unique town, placing it against the historical considerations which shaped or influenced the development of these Caribbean Historical Centres, as a reason for safeguarding and preserving some of its attributes.

It is said that the first West Indian Towns were not planned, they grew up as small collections of huts near the forts. Their purpose was strictly utilitarian – shipping points, with a line of house stretching along the shore. A second street parallel to the one along the shoreline was added when needed, with alleys or small cross streets connecting the two. The streets were narrow twisting streets lined with tall houses built closely together, but the focus on the town was on the fort.

The location of a town was determined by the presence of a good anchorage and a source of fresh water. An added advantage was an area where ships could be careened to have the barnacles scrapped off their hulls. As these shoreline towns grew, the street along the sea’s edge became lined with warehouses, each extending out on a private wharf, on the seaward side. On the upper side of this main street,were shops with living quarters above, and other streets had more of these shop/townhouses. The fort and the customs house occupied the central location.

Thus it could be said that West Indian Towns were based on trade. Because of this trade, which constantly brought a wealth of influences to anchor at their wharf, they contain architecture of a more cosmopolitan nature than that of the plantations. National differences exist among the towns of the West Indies, but the basic nature of the architecture, functional as it were, remains very similar whether the builders were English, French or Dutch.

Tradition and the relative high value of land in town led to the practice that was demonstrated to be not only impractical in the West Indies but often deadly. Another dangerous practice in town building was the use of timber and thatch, which made the early towns vulnerable to a series of devastating fires. In the 18th and 19th Century, an attempt was made in several islands to introduce building codes specifying the use of non-flammable material, the distance between building and their maximum height. These were difficult to enforce thus towns continued to suffer from frequent fires.

In the English Speaking Caribbean, Kingston, Jamaica, has been identified as the first planned town. It was laid out after the earthquake which destroyed the first town of Port Royal in 1692. The Spanish, who had already established themselves in Hispaniola, had been building planned towns with a regular grid of streets centring on an open square from the beginning, and when the English took Jamaica from the Spaniards they rebuilt Spanish Town.

It might seem that given the opportunity to build new towns from the ground up, in the colonies, the settlers would erect towns that showed the influence of formal town-planning but their utilitarian viewpoint was against this. The simple grid-iron was the most efficient and that is how the planners of Kingston laid out the City. Instead of focusing the streets of the town on important buildings or squares, they still planned a seafront.

The new cities were loyal to the architecture of the Mother Country. Portuguese and French towns tended to grow freely while Spanish cities were generally carefully planned and rigidly gridded. Coastal towns and towns along the silver frontier were fortified while others were left open. The core of each city was monastery, overlooking a plaza, then surrounded by administrative buildings: town hall, jail, hospital, slaughter-house.

By 13 July 1573 a set of comprehensive Laws of the Indies codified planning practice in 148 articles. Her are some examples: “Preaching the gospel is the principle objective for which we mandate that these discoveries and settlements be made.” (36) License had to be granted to begin a town. Article 111 gives the site of a town: the Plaza is the starting point of any scheme. Its dimensions had to be proportioned to the intended size of the town; no less than 61 by 91 m., but no more than 162 by 243 for a city. From here streets would sprout from the Plaza: one from the middle of each side and two from each corner forming right-angles.

Surrounding the plaza there had to be arcades (portales) for commercial usage; streets had to run free of these arcades with a sidewalk. The church had to be near the centre and visible to seafarers if the scheme concerned a coastal town. Grouped around the church you had the town hall, hospital, royal council, customs house; further out were the slaughter houses, fisheries, tanneries etc. Each of these were allotted full blocks. The other plots were distributed by lottery. No settler could receive more than 5 peonias (a plot of 15x30 m.) or three cabelleries: houseplots of 30 x 60 m. Settlers were given grain, seeds and animals. It was incumbent on the settlers to provide their plot with closed boundaries. A settler accepting a plot was duty-bound to build on it quickly, work the land and acquire herds. Sheds had to be built to keep horses and animals and had to have yards and corals. “The buildings shall all be of one type for the sake of the beauty of the town” (article 134); “the town shall maintain a plan of what is being built” (article 137). These rules go back to advice in books from the Renaissance architects in Italy such as Serlio and Alberti.

The most important architect of the Veneto, “the most imitated architect in the world,” and a direct contemporary of Sinan across the Mediterranean Sea, Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) was trained as a stonemason and then adopted by the foremost humanist of the period and the area: Count Trissino who like many gentlemen aristocrats from Venice had escaped from the bustle and overcrowding of Venice to the Country, where they tried to develop alternative sources of income to trade by farming the land. To encourage this gentlemanly pursuit many idealized the countryside and country-living. As a result the villa became an integral part of the landscape, opening out to it, embracing parts of it, looking out over it and reversing the protective geometry of the town-house and town palace with its inward looking courtyard life.

The primary purpose of these urban enclosures, of course, was to protect the cities they surrounded. But they also had numerous side effects, both good and bad, upon the growth and life of their wards. Every fortified city bore the stamp of its defences and even today, with most of the former fortifications either built over or razed, cities that had once been fortified retain much of the character that had been shaped by their encirclement.

Perhaps the most important among the positive effects of an encasement was its function of effectively controlling urban sprawl. Walls established definite limits for a civic organism; they set it off emphatically from the surrounding countryside and firmly enclosed all major civic activities within their boundaries. Renaissance humanists liked to compare them to the skin of the human body that held the inner organs in place. Walls framed and monumentalized the urban fabric, they made it a dominant focal point of the landscape and gave it the stamp of individuality. Few walled cities looked alike, and citizens could identify with their home town to a degree that modern man, mobile again and accustomed to standardized and relative featureless urban pictures, will find difficult to appreciate. Well-designed and constructed walls were objects of civic pride and regarded as prime indicators of a city’s wealth and power. The universal importance attached to them in the past is amply reflected in hundreds of ancient and medieval pictorial representations in which towered ring walls were used as standard symbols for “city.”

Mountain plateaus, hilltops, and peninsulas were usually regarded as most easily defensible. Foundations on open plains meant either that the founders had confidence in their ability to defend the city under adverse conditions, or that considerations other than safety were more important to them. Once chosen, the site would impose itself upon the city in varying degrees. On a hilltop, for instance, the area was usually restricted and the city’s propensity for growth limited; regular street plans were rarely possible or practicable, and building density tended to be high. On a flat and open plain, on the other hand, growth was limited primarily by traffic and economic considerations; regular street plans were both possible and frequent, but the problem of defence became more complex and its solutions more expensive.

Within the limitations dictated by its site, a city could develop in one of two basic fashions: it could be built up according to a predetermined plan, or it could be permitted to grow naturally by agglomeration into an unplanned city. Fortifications might be added to the urban body at any stage of its development. Frequently the site was fortified first and the city built later into its prepared defences. No matter what the sequence, the planning of an encasement was crucial for the town’s subsequent development. If the defensive line was drawn too loosely, defence became more difficult as interior lines of communications were lengthened and more manpower was needed to man the ramparts. Throughout history planners were vexed by this choice and their answer generally had to be a delicate compromise between the needs of the moment their expansion for the town’s future.

Other knotty problems that constantly faced planners were the manner in which a city’s street plan should be adjusted to its fortifications, and the extent to which civilian convenience should be subordinated to military demands. Often the problem was side stepped, as street plans and defences were treated as separate and independent elements. But even in unplanned cities that were surrounded by walls, which were unrelated to the urban body, the number and placement of gates would invariable raise problems. Since city gates were usually considered to be the most vulnerable spots of a defensive system, their number had to be kept at a minimum and their placement carefully planned. Thus, traffic in and out of a town became automatically restricted; the inconvenience to civilians could be, but was not always, alleviated if street plan and fortifications were designed in unison. This type of unified planning, found in colonial foundations of all periods, became the rage during the Renaissance.

Fort Annunciation, (as it was established on the feast of the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary, March 19th – 25th 1649), later called Fort Louis could be considered as the first town built in St. George’s. Built on the sand spit which separated the harbour and the lake, the town comprised of a palisade fort, with earthen ramparts, a musket proof block house, huts and a large wooden prefabricated building brought in from Martinique.

The cutting of the trees and the cultivation of the land soon brought about mass erosion, especially during the rainy season when the lake received extra water from the surrounding hills and streams resulting in a high water table. Moreover, during the rainy season, the land was constantly flooded thus forcing the abandonment and relocation of the town in 1700 to the western side of the harbour, today’s present day site.

It is believed that the sand spit sank or was flooded over by the sea during the 1850s. It was further affected by the volcanic disturbances of 1902 and 1920. However, in order to accommodate larger crafts, a first channel was dredged in 1960 and again in 1998. Today, remains of the sand spit could still be seen from the premises of the Grenada Yacht Club and from the pasture at the lagoon, while the land formation could still be seen lying under the greenish looking water of the lagoon.

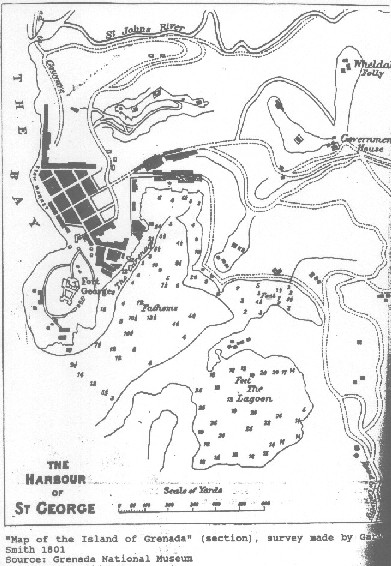

Early plan of St George (click on image to see larger view)

This new town, called Fort Royal, was centred or developed mainly around an old 1600s coastal battery built upon the promontory which separates the town at an elevation of 160 feet above sea level. The main emphasis was placed on the fort as it overlooked the important administrative and institutional buildings such as the governor’s residence, the colonial treasury, court house, legislative building, goal, customs and warehouses.

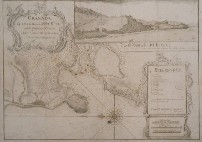

Early plan of Fort Royal (click on image to see larger view)

Another 1700s plan of Fort Royal (click on image to see larger view)

Around the early 1700s, due to the prosperity of the settlement which saw its expansion and construction of new fortifications, early forms of planning became evident as the town was laid out on a grid system, with a square or plaza. However, this was a military square for the soldiers and the militia. Also noticeable is the commencement of buildings along the Carenage, Herbert Blaize Street and Lucas Street. Quite interesting, they were given Roman names, Upper Monstrat and Lower Monsterat. Fort Royal was developed into a small bastion square fort while the northern boundaries of the town ended with the St. John’s River. Parts of today’s cemetery close to the Green bridge were used as the chief landing place for ordnance and stores for the forts at Hospital Hill.

A series of early plans

Fort Royal (click on image to see larger view)

Early plan of St George (click on image to see larger view)

Early plan of St George (click on image to see larger view)

Early plan of St George (click on image to see larger view)

Early plan of St George (click on image to see larger view)

Early plan of St George (click on image to see larger view)

Early plan of St George (click on image to see larger view)

A sequence showing St George and its Market Square over 200 years

St George in the 1790s (click on image to see larger view)

Market Square 1840s (click on image to see larger view)

St George's 1900s (click on image to see larger view)

Market Square 1930s (click on image to see larger view)

Market Square 1940s (click on image to see larger view)

Market Square 1960s (click on image to see larger view)

Market Square 1990s (click on image to see larger view)

A sequence of general views of the area

Bay Town 1790s (click on image to see larger view)

Bay Town 1830s (click on image to see larger view)

Bay Town 1880s (click on image to see larger view)

Bay Town 1960s (click on image to see larger view)

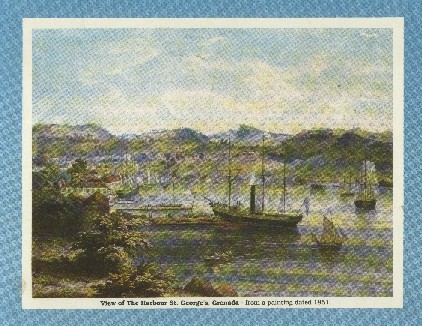

The Harbour (click on image to see larger view)

The Harbour 1850s (click on image to see larger view)

Bay Town (click on image to see larger view)

The Carenage (click on image to see larger view)

The Carenage (click on image to see larger view)

The Carenage 1930s (click on image to see larger view)

The Anglican Church (click on image to see larger view)

The Palma Fire (click on image to see larger view)

| Grenada, May 9. 1776 |

| N Thursday night last about 9 o’Clock, Came to an anchor in the Bay, from London, The Ship Earl of Errol, Capt. John Bartlet, in which came, The Right Honorable S I R G E O R G E M A C A R T N E Y K: B: his LADY, and Family, and on Friday about 12 0’Clock, he landed at the King’s Wharf, Carnash, where the 48th, Regiment Were ready to receive him, and all other Marks of honor were paid his Dignity. His Honor Fredrick Corsar Esq. The President, with many Principal Gentlemen, were present on his Landing; after which he was conducted by the Provost Marshal to the Court House, where he took the usual Oaths. – The Honorable the Members of his Majesty’s Council and House of Assembly, (prior to his arrival) provided an elegant Entertainment, at the Villa, a House taken for his Excellency, where a numerous Company were at Dinner, and in the Evening Excellency and Lady went to Thomas Townsend’s Esq; And on Saturday they visited the Honourable Patrick Maxwell Esq; Calliviny, where they remained until Last Monday, and then returned to the Villa. |

The street now known as "Church Street", running from the conjunction of Young and Halifax Street to its junction with the top of St. John's Street, was probably known, initially as part of Grand Etang Road. More recently, it was known, until sometime in the 1920s, by two names. A diagram indicates that roadway from the conjunction of Young and Halifax Street to Simmons Street was known as "Government Street".

From the junction with Simmons Street, beyond York House and to St. George's Cemetery at top of the hill, was known as "Hospital Street". That street got its name from the fact that originally it led to a hospital at the top of the ridge, established in 1736 during the French colonisation of the island ("Health in Grenada": Clyde, Page 10/11) That hospital remained in use until 1859 when the patients were moved to the vacated barracks beneath Fort George, the site of the present General Hospital.

However, it should be noted that Church street was first called Government Street (Rue du Gouvernement) because it was once the location of all the main Governmental Offices when the town was moved to it new location. Therefore, it was the home of the Colonial Treasury or Le Bureau du Domaine and at one time even housed the Le Palais. It is quite interesting to know that Church Street was only the area which took you from Government Street on to Scott street via the steps or today’s Simmons alley.

A list of Estates in Grenada, (relative to the Garvin Smith Map) compiled in 1801, shows the proprietors of six estates to be Trustees of Deponthieu. There were Good Hope, 215 acres, Beaulieu 389 acres, Azimar 256, Ithaca 117 acres, Thuilleries 238 acres and Meranc 160 acres.

The list of estates was compiled some 10 years after the Fedon Revolution of 1795 and some estates are listed as "Forfeited" indicating that their owners supported the defeated Fedon.

The name "Deponthieu" suggests French nationality and the fact that the six estates were not forfeited suggests that Deponthieu supported the British in the fight against the rebels. The number and size of the estates indicate a person of some prominence, important enough to have a street named after him.

Deponthieu Street is also known as "Cockroach Alley." Early in this century, this street was notorious as a red-light area and at the time a euphemism for prostitute was cockroach.

This street named in honour of Hon. Fitzmaurice, a member of the legislature, once linked Irvin Street to the waterfront. Today it is enclosed by the Hubbards Hardware Department. However it is quite interesting to note that when walking through that department towards the area with the glass, steel and galvanize, you will have to walk on the flat cobble-stones of this former street

Alley now called Simmons alley

This street once was linked from today's site of the St. James Hotel to Young Street. Parts of this street, although blocked up, are still visible at the entrance to the Ministry of Communication and Works and at the back of the buildings along Young Street.

New Port (click on image to see larger view)

Croix Horst De La, Military Considerations in City Planning: Fortifications, Columbia University, 1972.

Jessamy Michael, Forts and Coastal Batteries of Grenada, 1998.

Gosner Pamela, Caribbean Georgian, The Great and Small Houses of the West Indies, Washington, D.C., 1982.

Salcedo Jaime, Urbanismo Hispano-Americano, Siglo XVI, XVII Y XVIII, El Modelo urbano aplicado a la America Espanola, su genesis y su Desarrollo teorico y practico, Bogota, 1994.

Voorthuis Jacob, A Resume of Buildings and Issues Dealt with During the 1995 Michaelmas Term: The European Expansion

© Michael Jessamy, 2002. HTML last revised 15 February 2002.

Return to Conference Papers.