Painting by Susan Mains, click on picture to see a larger image

One of the most defining moments of my artistic career was when an officer attached to the Ministry of Culture turned down the Art Council's request for funding to send an exhibit overseas. The reply given was, "Art is not a part of culture." Since that time more than five years ago, I have observed in many ways that visual art is the "outside child" of our institutional cultural milieu. I am an artist. Because my art education has been self-inflicted, it took me a long time to be brave enough to say, "I am an artist." I did not go to school to become an artist. My inner creativity was expressed at an early age. When given a "paint by number" set of a portrait of a horse, I ignored the numbers and lines and painted a landscape scene of the cane field and old windmill that I saw out my window from our residence in Barbados. My parents, themselves educators, encouraged me to be a teacher. They viewed art as a nice hobby, but certainly not something that would sustain a girl in for the future.

Three degrees in education later, I still had a deep need to express myself in colour and paint. Living in Dominica at the time (teaching, of course), a teenager would often come to our house to visit. He was a nascent artist himself, and when he saw my amateurish attempts at painting, he told me "You could do much better than this." He began to give me constructive criticism, and I started to paint in earnest. Thus began a journey in visual art that continues to this day. When I returned to Grenada to live permanently in 1992, I immediately began to paint scenes from Grenada, and exhibit with the Grenada Arts Council. For many, many years the Grenada Art Council had hosted an annual show at Marryshow House. As a teenager I had visited the exhibit every year - admiring the work, longing to know the secrets of the artists - how did they do that? I believe that my history is typical of that of many small islanders; the desire to create art very strong, yet the opportunity, limited. The reality of the state of visual art in Grenada is that it enjoys no institutional support. Following are some examples of this. Art education in primary and secondary school is very limited. When it is offered in secondary school it is often relegated to those "who can't do so well academically." A principal once told me that the only reason they prepare students for Art for the CXC is so that some students can "at least get one O level." The traditional materials and supplies needed to do art are expensive. The customs duty and the VAT tax, and the surcharge and this that and the other often add up to about 65% added to the price of such items. A secondary teacher from St. Andrew's shared with me that he was teaching calligraphy to his students, but couldn't find the correct pens for them to practise with. When I asked him about importing them for him, his response was, "Ah, but they wouldn't be able to afford to buy them anyway." And this is quite true. Mr. Gordon de la Mothe, whom I will speak about later, shared with me that he left Grenada some 50 years ago with a Certificate in Art being the most he could obtain here. After studying and teaching art in England all these years, he returned to Grenada in 1997 to find that the situation was just the same. Aside from material considerations, an even deeper problem exists for teachers wishing to teach art. For the most part, our teachers in Grenada pass on what they have been taught in school. Art history has never been a part of the core curriculum. Art is often conceptualized just as the object that is produced, thus assigning it to the category of a product. Also, there is no differentiation between art and craft, (craft being an item that can be reproduced over and over). For the teaching of art to be a reality in our primary and secondary schools the teachers themselves must have an understanding of what art means in their lives. In the past I have taught workshops for teachers in "how to teach art." We learned colour theory, we played with interpretation, we collected dried grasses, seeds, coconut fibre and other natural items to be made into art. We made the projects together; fun and excitement was the order of the day. Many of the teachers expressed the view that they had never done anything like that when they were in school. I thought, "Great, I have made an impact. I have shown them how to use local materials to make art. These are things that are readily available, and don't cost much. This will be a beginning of art in primary schools! Who knows which young Picasso will come forth because of this exposure. Yeah!" I visited these teachers in their classrooms a few months later to see what the lasting impact of the course was. I was sadly disappointed. Art class was "take your pencil and tear a page from your exercise book and draw something you like." Sigh. I could not effect positive change with a single course. It takes many interactions from many sources to enhance a person's perception of the intrinsic value of self-expression. This dilemma is broader than the educational system. We have not been endowed with a national appreciation for visual art. Aside from the visual trappings of Carnival, we do not perceive art as a necessary part of our cultural environment. Take, for example, the "Festival of the Arts" which has been produced by the Ministry of Culture every two years for decades. While dance, drumming, choirs, soloists, instruments, and other performing arts are very successfully encouraged, the visual arts are not even included. Art is not present in public spaces. When you walk into a government office, even in the Ministry of Culture, you do not see art on the walls, nor when you enter the country at the airport or seaport. Monuments have not been a part of what we leave behind for the next generation. Even the preservation and collection of Grenada's art has not been a priority. We have no Museum for the display of visual art. This lack of institutional support exhibits itself in the practical. When an exhibition of Grenada's art is shown in another country, we are required to go through the same process with customs as if we were exporting goods for sale. One such occasion took me no less than seven visits to different ministries, hiring a broker to prepare paper work, carrying the papers back to the customs officer, finally to the Comptroller of Customs, all to ensure than after the work was exhibited abroad, when it came back we would not have to pay duty on it. Mind you these were works of art created in Grenada by Grenadian artists. There is no legislation regarding the exchange of art for exhibition between countries; every interchange is taken on an individual basis, thus going over the same ground again and again. If we look to our history there are many reasons as to why as a nation we have evolved in this way. It is beyond the scope of this paper to study the aspects of colonialism, independence and nationhood and its effect on the visual arts. Therefore, we do not look back to cast blame at any source, but we look forward to forge a strong foundation for the future. History aside, we can no longer ignore this strong tool for developing nationalism and cultural identity. I believe that the visual arts are a sustainable resource that should be utilised in nation building. This term "sustainable resource" is most often used in the context of agriculture, eco-tourism, fisheries, or some other earth related science. The word "sustainable" first appeared in 1727, having the definition of relating to, or being a method of harvesting or using a resource so that the resource is not depleted or permanently damaged.1 And yet another follows a similar vein: The sustainable resource in our scenario is the creativity of the human spirit. It is actually an intellectual resource, but needs the material and the physical to be expressed. Like the resources of the earth, it can be abused, and used up. Like the products of agriculture, if not given water and fertilizer and care, it will not thrive. It involves:

Sparks of creativity abound in the Grenadian community, but this resource must be cultivated and invested in to reap the fullness of the potential reward. In the past decade Grenada has become an environment where the nutrient pool is rich for creative potential. We have had unlimited access to the press and news of the world through television and the Internet. There is free speech and freedom to practice the religion of one's choice. Freedom of expression has never in our history been so free. And in a time where the world is at war, we in Grenada live in peace. The conditions are superb for a cultural awakening. It is a time to invest in Grenada's culture and proudly interpret it visually and display it as our own. The freedom of information we currently enjoy, however, comes at a high price. Our children, young people, and adults are bombarded with visual images from North America via the TV, the Internet, and designer clothing. The effect is that these images then become the story we tell, rather than our telling our own story. A proactive program of cultural intervention must be embarked upon if we wish to have anything left of ourselves to pass on to the generations to come. By intervention, I mean the active role of helping to synthesize these ideas from the outside, interpret them within the local context, accept some, reject some, but not let them overwhelm us and replace us. Defining who we are as illustrated by our visual art then becomes the mortar for nation building. I am not suggesting that every painting must be one with a little wooden house, a donkey carrying goods to market, the men working in the fields, and the women washing in the river. While these portray a glimpse into a fast-fading Caribbean way of life, this is not our whole story. Abil Peratta Aguero, an art critic of the Dominican Republic writes:

Sustainable production and consumption involves business, government, communities and households contributing to environmental quality through the efficient production and use of natural resources, the minimization of wastes, and the optimisation of products and services.2

All these then contribute to the creative quality of life.

Old clichés have been underlying a conception of Caribbean culture as an active element of the international tourist industry. ...most of the rest of the world see the Caribbean as a region of small states where typical aspects of wild, exotic, funny and supernatural reign.… However, reality is different. We are essentially a culture of real passions and dreams.3

In other words, we have much more to express than just the typical scene that a tourist may purchase for a souvenir.

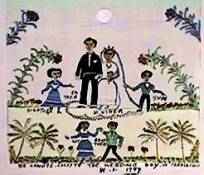

Recently I encouraged an expatriate now living in Grenada to collect Grenadian art. Her response was, "Oh, but I couldn't buy yours — it isn't Grenadian." Asking for further explanation, she replied to me, "It doesn't look like the simple work of Canute Caliste. It isn't primitive enough." Apparently she had been convinced that only the very naïve type of work was truly Grenadian art. She is sadly misinformed.

Visual art in its true essence gives the artist the opportunity to express his or her innermost thoughts and expressions within the context of his time and culture. This expression can take many forms - it could be representational, as in the traditional painted European format, or it could follow the impressionist movement of a hundred years ago. It could be abstract, or expressionistic. Further, it may be a sculpture, tooled into being out of piece of local hard wood. It could be an installation of found objects that is only temporarily put on display to express a particular idea or notion. More importantly, what should be expressed in the art of now is understanding where we have come from and dealing with the issues of our day, exposing our ideas, and staking claim to our own expressions as valuable in their own right. It will be influenced by the outside world, but we must understand that influence, put it into context, and not just accept it without question. What makes it Grenadian art is that the ideas and expressions are germinated within the Grenadian cultural environment. That environment may be here, or it may be in the mind of a Grenadian living anywhere in the world. It may be done by any number of foreign nationals who live in Grenada, and are influenced by the local culture. So if it is the very abstract work of Oliver Benoit, or the naïve work of Elinus Cato, it is Grenadian art.

When considering an investment into a sustainable resource, the question will arise - what will be the benefit? Is this investment one that will continue to give yields far into the future? I have already touched on the benefit of nation building, and strengthening of cultural identity. Let me venture into areas a little less esoteric. The reality of being an artist anywhere in the world is that artists have to eat, too. Thus comes the reality that works of art must be sold to sustain the artist, to provide money for materials to continue to make art. The somewhat unique position an artist in Grenada has, is that the world comes to Grenada to holiday. And when they come and enjoy the pristine beauty of Grenada and the warmth of the Grenadian people, they wish to take a piece of that back to their home with them. They want to relive that experience in their minds again and again. A piece of art can be that bridge for them to return. Further, some tourists come to Grenada specifically for Grenada's art. Our 87-year-old gentleman painter of Carriacou, Canute Caliste, has had visitors from around the world come to visit him in his studio, after reading an article about him in a travel section of a newspaper or magazine.

Grenada's art has the capacity to bring many tourists to our shores. These tourists stay in hotels, eat in restaurants, ride in taxis - spend dollars. Again, if the resource of the visual arts is to yield benefit, it must be invested into in the area of marketing. When foreign investors develop hotels here, it should be mandated that some of the art they use to decorate their lobbies and rooms be created by Grenadian artists. What better venue for exposing Grenada's art to visitors? Further, artists themselves must be recognized as individuals who contribute to the building of Grenada's economy. Thus the same concessions given to fishermen and farmers in allowing them to bring in equipment duty free should be given to artists as they bring in their equipment and supplies. Just as the Ministry of Sports pays the exit tax for athletes when they travel to compete, the Ministry of Culture could pay the exit tax for artists when they carry an exhibit of Grenada's art to be shown outside. And this leads to the issue of Grenadians collecting our own art. One local businessman was boasting of his terrific purchase of paintings when he was visiting Haiti. "They were so cheap" he said, "I just couldn't help it, I bought 15 of them." I am sure that the walls of his home are now bright and pretty, but what does that say for his appreciation of Grenada's art? Does he know the names of those Haitian artists? Will he follow their careers? When they are exhibited in an important world exhibition, will he know? Will that work increase in value in the future? If it does, will he be aware? Or are they just pictures to "stick up on the wall." The money for the purchase of those paintings, no matter how "cheap," is now circulating in Haiti, not in Grenada. This isn't to say that Grenadians should not collect the works of artists of other countries, but at some point we need to consider nationalism. We suffer from the common misconception that anything from anywhere else is of better quality and more valuable than what we can get here. In speaking with the owners of two local art galleries, I was informed that more than 90% of their sales are to tourists. This is a double-edged sword. While good economically, it also means that most of Grenada's art is being carried away from Grenada - never to be seen by the next generation. This leads to yet another investment that must be made; a permanent space for the visual arts to be displayed in Grenada. This should take the form of a National Museum for Visual arts, including additional space for an educational component. The Grenada Art Council for the past five years has been collecting important pieces of Grenada's art with the concern that it be preserved for Grenadians. Unfortunately, the collection is in storage, because of lack of an adequate facility.

The investment for a permanent space is a large one. Government must take the lead in such a venture. There is funding available through many sources: The Organization of American States, the European Union, the World Bank, but this must be accessed on the level of Government. This investment into a structure of such a building is in reality an investment into the potential of people-an investment into the preserving the past for the benefit of the future.

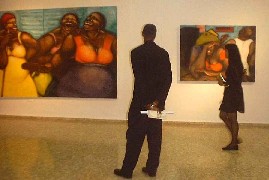

In spite of these many challenges, the visual arts in Grenada are alive and well. Grenada has been well represented in world exhibits such as the IV Bienal de Arte Carib in Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic that is currently underway. (November 2001-February 2002) A few of Grenada's artists have exhibited in galleries in North America, holding their own with the best of artists of the big countries. The Grenada Art Council continues on a yearly basis to provide an exhibit for any artist who wishes to participate. They do this without any government subvention, but with the voluntary support of the business community and individual patrons of the arts. Often this is the only avenue for beginning artists to display their work. Over a hundred artists are on their list of those who have participated in the last few years. This is a significant number. It has several times taken on the monumental task of sending exhibits abroad. Grenada's art has been taken as a cultural ambassador to Barbados, The Dominican Republic, Germany and the United States. During the 37-year history of the Council, it has at times been the only candle burning in the night for the visual arts.

Mr. Gordon de La Mothe is a Grenadian who returned after many years of teaching art in England. Since 1999 he has rendered his services at the T.A. Marryshow Community College. Taking students who have virtually no background, he is preparing them for "A" level examinations in art. The very encouraging aspect of this is that two of his students who were successful in obtaining passes are now teaching art in secondary schools. It is a beginning.

The Sissons Paint Company has locally been developing an artist quality acrylic paint. It is of good student grade quality, and available at a price that is much cheaper than the imported variety. This is very positive for schools and students. In the year 2001, Caribbean Art Exchange was formed with links in Grenada and Miami, with the vision of exposing Grenadian artist to the works of other Caribbean artists and vice versa. The first exchange was held in February of 2001, with four Grenadian artists displaying their work at the Diaspora Vibe Gallery in Miami. The second exchange will take place in March of 2002, when

Rosie Gordon-Wallace, founder of the Diaspora Vibe Gallery and a U.W.I. graduate, will bring the work of four Caribbean artists to be displayed in Grenada. Seminars and workshops in the visual arts will be a part of this exposure. The co-operation of the U.W.I. centre in Grenada has played a vital role in this exchange, and we look forward to an explosion of interest from the local arts community in support of this effort. The interesting concept of considering the visual arts as a sustainable resource is that the development of human potential is not something that can be quantified in numbers or statistics. It cannot be measured in terms of how many acres will produce how many tons of bananas. It is not a pie with only so many pieces to be shared. But like agriculture and fisheries, it must be invested in to. Structures must be put into place to encourage the spirit of creativity in individuals, to develop skills to execute their ideas, to provide vehicles to exhibit their work both in Grenada and abroad, and to ultimately instil in a new generation a strong sense of pride of who we are as a people as expressed by our visual art. This investment must come in several areas, education being key. Education in the visual arts must be enhanced in the primary and secondary schools, provided via programs on the local TV community channel, offered in community and church groups. The investment must come in government and local business buying art from local artists to display on their walls. The Ministry of Culture could begin to take a more active role by assigning a department to the visual arts, and budgeting for its activities. And finally, government and the private sector must join the art community in making a permanent space for Grenada's art to be preserved. This space would include the permanent exhibition of Grenada's art, as well as an educational aspect for documentation and research.

Art, as a sustainable resource, is exemplified by Gilbert Nero. He was young, out of school, and "liming on the blocks." A local gallery owner gave him some paint and a few instructions. When Gilbert didn't have money to buy canvas, he begged his mother for old bed sheets, which she gave, and he painted on those. Gilbert continued to come back for criticism, instruction, and help. He exhibited with the Grenada Art Council in 1997, displaying a huge painting of a fanciful insect - his own interpretation. His large painting of sailing boats now hangs behind the bar at Secret Harbour Hotel. Art changed his life. It took him away from "the blocks" and the temptation to give in to the use of drugs; it gave him confidence, and told him that his story was important, too. He is now working on a cruise ship, and every time he returns to Grenada he brings his latest works of art with him.

With or without institutions for support, artists will continue to exist in all countries, even Grenada. The question is, will the country benefit from those artists, culturally, socially, and economically? As our society develops, the need for artists to be the interpreters and the storytellers becomes even greater. I encourage our government, our schools, and our private sector - make the investment into this sustainable resource now. If you ever have to wonder if the potential is really there, just remember another storyteller of Caribbean origin. His name was Bob.

1

http://envirosystemsinc.com/sustainable.html2

Edwin G. Falkman, Waste Management International. Sustainable Production and Consumption: A Business Perspective. WBCSD, n.d.3

Abil Peralta Aguero, "Sacha Tebo: un Maestro del Caribe", Cariforum April 2001, No 4© Susan Mains, 2002. HTML last revised 11 February 2002.

Return to Conference Papers.