PLATO,

AND THE

OTHER COMPANIONS OF SOKRATES.

BY GEORGE GROTE

A NEW EDITION.

IN FOUR VOLUMES.

Vol. IV.

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

215

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

TIMÆUS AND KRITIAS.

Persons and scheme of the Timæus and Kritias.

Though the Republic of Plato appears as a substantive composition, not including in itself any promise of an intended sequel — yet the Timæus and Kritias are introduced by Plato as constituting a sequel to the Republic. Timæus the Pythagorean philosopher of Lokri, the Athenian Kritias, and Hermokrates, are now introduced, as having been the listeners while Sokrates was recounting his long conversation of ten Books, first with Thrasymachus, next with Glaukon and Adeimantus. The portion of that conversation, which described the theory of a model commonwealth, is recapitulated in its main characteristics: and Sokrates now claims from the two listeners some requital for the treat which he has afforded to them. He desires to see the citizens, whose training he has described at length, and whom he has brought up to the stage of mature capacity — exhibited by some one else as living, acting, and affording some brilliant evidence of courage and military discipline.1 Kritias undertakes to satisfy his demand, by recounting a glorious achievement of the ancient citizens of Attica, who had once rescued Europe from an inroad of countless and almost irresistible invaders, pouring in from the vast island of Atlantis in the Western Ocean. This exploit is supposed to have been performed nearly 10,000 years before; and though lost out of the memory of the Athenians themselves, to have been commemorated and still preserved in the more ancient records of Sais in Egypt, and handed down through Solon by a family tradition to Kritias. But it is agreed between Kritias and Timæus,2 that before the former enters upon his quasi-216historical or mythical recital about the invasion from Atlantis, the latter shall deliver an expository discourse, upon a subject very different and of far greater magnitude. Unfortunately the narrative promised by Kritias stands before us only as a fragment. There is reason to believe that Plato never completed it.3 But the discourse assigned to Timæus was finished, and still remains, as a valuable record of ancient philosophy.

The Timæus is the earliest ancient physical theory, which we possess in the words of its author.

For us, modern readers, the Timæus of Plato possesses a species of interest which it did not possess either for the contemporaries of its author, or for the ancient world generally. We read in it a system — at least the sketch of a system — of universal philosophy, the earliest that has come to us in the words of the author himself. Among the many other systems, anterior or simultaneous — those of Thales and the other Ionic philosophers, of Herakleitus, Pythagoras, Parmenides, Empedokles, Anaxagoras, Demokritus — not one remains to us as it was promulgated by its original author or supporters. We know all of them only in fragments and through the criticisms of others: fragments always scanty — criticisms generally dissentient, often harsh, sometimes unfair, introduced by the critic to illustrate opposing doctrines of his own. Here, however, the Platonic system is made known to us, not in this fragmentary and half-attested form, but in the full exposition which Plato himself deemed sufficient for it. This is a remarkable peculiarity.

Position and character of the Pythagorean Timæus.

Timæus is extolled by Sokrates as combining the character of a statesman with that of a philosopher: as being of distinguished wealth and family in his native city (the Epizephyrian Lokri), where he had exercised the leading political functions:— and as having attained besides, the highest excellence in science, astronomical as well as physical.4 We know from other sources (though Plato omits to tell us so, according to his usual undefined manner of designating contemporaries) that he was of the Pythagorean school. Much of the exposition assigned to him is founded on Pythagorean 217principles, though blended by Plato with other doctrines, either his own or borrowed elsewhere. Timæus undertakes to requite Sokrates by giving a discourse respecting “The Nature of the Universe”; beginning at the genesis of the Kosmos, and ending with the constitution of man.5 This is to serve as an historical or mythical introduction to the Platonic Republic recently described; wherein Sokrates had set forth the education and discipline proper for man when located as an inhabitant of the earth. Neither during the exposition of Timæus, nor after it, does Sokrates make any remark. But the commencement of the Kritias (which is evidently intended as a second part or continuation of the Timæus) contains, first, a prayer from Timæus that the Gods will pardon the defects of his preceding discourse and help him to amend them — next an emphatic commendation bestowed by Sokrates upon the discourse: thus supplying that recognition which is not found in the first part.6

Poetical imagination displayed by Plato. He pretends to nothing more than probability. Contrast with Sokrates, Isokrates, Xenophon.

In this Hymn of the Universe (to use a phrase of the rhetor Menander7 respecting the Platonic Timæus) the prose of Plato is quite as much the vehicle of poetical imagination as the hexameters of Hesiod, Empedokles, or Parmenides. The Gods and Goddesses, whom Timæus invokes at the commencement,8 supply him with superhuman revelations, like the Muses to Hesiod, or the Goddess of Wisdom to Parmenides. Plato expressly recognises the multiplicity of different statements current, respecting the Gods and the generation of the Universe. He claims no superior credibility for his own. He professes to give us a new doctrine, not less probable than the numerous dissentient opinions already advanced by others, and more acceptable to his own mind. He bids us be content with such a measure of probability, because the limits of our human nature preclude any fuller approach to certainty.9 It is important to note the modest pretensions 218here unreservedly announced by Plato as to the conviction and assent of hearers:— so different from the confidence manifested in the Republic, where he hires a herald to proclaim his conclusion — and from the overbearing dogmatism which we read in his Treatise De Legibus, where he is providing a catechism for the schooling of citizens, rather than proofs to be sifted by opponents. He delivers, respecting matters which he admits to be unfathomable, the theory most in harmony with his own religious and poetical predispositions, which he declares to be as probable as any other yet proclaimed. The Xenophontic Sokrates, who disapproved all speculation respecting the origin and structure of the Kosmos, would probably have granted this equal probability, and equal absence of any satisfactory grounds of preferential belief — both to Plato on one side and to the opposing theorists on the other. And another intelligent contemporary, Isokrates, would probably have considered the Platonic Timæus as one among the same class of unprofitable extravagancies, to which he assigns the theories of Herakleitus, Empedokles, Alkmæon, Parmenides, and others.10 Plato himself (in the Sophistês)11 characterises the theories of these philosophers as fables recited to an audience of children, without219 any care to ensure a rational comprehension and assent. They would probably have made the like criticism upon his Timæus. While he treats it as fable to apply to the Gods the human analogy of generation and parentage — they would have considered it only another variety of fable, to apply to them the equally human analogy of constructive fabrication or mixture of ingredients. The language of Xenophon shows that he agreed with his master Sokrates in considering such speculations as not merely unprofitable, but impious.12 And if the mission from the Gods — constituting Sokrates Cross-Examiner General against the prevailing fancy of knowledge without the reality of knowledge — drove him to court perpetual controversy with the statesmen, poets, and Sophists of Athens; the same mission would have compelled him, on hearing the sweeping affirmations of Timæus, to apply the test of his Elenchus, and to appear in his well-known character of confessed13 but inquisitive ignorance. The Platonic Timæus is positively anti-Sokratic. It places us at the opposite or dogmatic pole of Plato’s character.14

Fundamental distinction between Ens and Fientia.

Timæus begins by laying down the capital distinction between — 1. Ens or the Existent, the eternal and unchangeable, the world of Ideas or Forms, apprehended only 220by mental conception or Reason, but the object of infallible cognition. 2. The Generated and Perishable — the sensible, phenomenal, material world — which never really exists, but is always appearing and disappearing; apprehended by sense, yet not capable of becoming the object of cognition, nor of anything better than opinion or conjecture. The Kosmos, being a visible and tangible body, belongs to this last category. Accordingly, it can never be really known: no true or incontestable propositions can be affirmed respecting it: you can arrive at nothing higher than opinion and probability.

Plato seems to have had this conviction, respecting the uncertainty of all affirmations about the sensible world or any portions of it, forcibly present to his mind.

Postulates of Plato. The Demiurgus — The Eternal Ideas — Chaotic Materia or Fundamentum. The Kosmos is a living being and a God.

He next proceeds to assume or imply, as postulates, his eternal Ideas or Forms — a coeternal chaotic matter or indeterminate Something — and a Demiurgus or Architect to construct, out of this chaos, after contemplation of the Forms, copies of them as good as were practicable in the world of sense. The exposition begins with these postulates. The Demiurgus found all visible matter, not in a state of rest, but in discordant and irregular motion. He brought it out of disorder into order. Being himself good (says Plato), and desiring to make everything else as good as possible, he transformed this chaos into an orderly Kosmos.15 He planted in its centre a soul spreading round, so as to pervade all its body — and reason in the soul: so that the Kosmos became animated, rational — a God.

The Demiurgus not a Creator — The Kosmos arises from his operating upon the random movements of Necessity. He cannot controul necessity — he only persuades.

The Demiurgus of Plato is not conceived as a Creator,16 but as a Constructor or Artist. He is the God Promêtheus, conceived as pre-kosmical, and elevated to the primacy of the Gods: instead of being subordinate to Zeus, as depicted by Æschylus and others. He represents provident intelligence or art, and beneficent purpose, contending with a force superior and 221irresistible, so as to improve it as far as it will allow itself to be improved.17 This pre-existing superior force Plato denominates Necessity — “the erratic, irregular, random causality,” subsisting prior to the intervention of the Demiurgus; who can only work upon it by persuasion, but cannot coerce or subdue it.18 The genesis of the Kosmos thus results from a combination of intelligent force with the original, primordial Necessity; which was persuaded, and consented, to have its irregular agency regularised up to a certain point, but no farther. Beyond this limit the systematising arrangements of the Demiurgus could not be carried; but all that is good or beautiful in the Kosmos was owing to them.19

Meaning of Necessity in Plato.

We ought here to note the sense in which Plato uses the word Necessity. This word is now usually understood as denoting what is fixed, permanent, unalterable, knowable beforehand. In the Platonic Timæus it means the very reverse:— the indeterminate, the inconstant, the anomalous, that which can neither be understood nor predicted. It is Force, Movement, or Change, with the negative attribute of not being regular, or intelligible, or determined by any knowable antecedent or condition — Vis consili expers. It coincides, in fact, with that which is meant by Freewill, in the modern metaphysical argument between Freewill and Necessity: it is the undetermined222 or self-determining, as contrasted with that which depends upon some given determining conditions, known or knowable. The Platonic Necessity20 is identical with the primeval Chaos, recognised in the Theogony or Kosmogony of Hesiod. That poet tells us that Chaos was the primordial Something: and that afterwards came Gæa, Eros, Uranus, Nyx, Erebus, &c., who intermarried, males with females, and thus gave birth to numerous divine persons or kosmical agents — each with more or less of definite character and attributes. By these supervening agencies, the primeval Chaos was modified and regulated, to a greater or less extent. The Platonic Timæus starts in the same manner as Hesiod, from an original Chaos. But then he assumes also, as coæval with it, but apart from it, his eternal Forms or Ideas: while, in order to obtain his kosmical agents, he does not have recourse, like Hesiod, to the analogy of intermarriages and births, but employs another analogy equally human and equally borrowed from experience — that of a Demiurgus or constructive professional artist, architect, or carpenter; who works upon the model of these Forms, and introduces regular constructions into the Chaos. The antithesis present to the mind of Plato is that between disorder or absence of order, announced as Necessity, — and order or regularity, represented by the Ideas.21 As the mediator between these two primeval opposites, Plato assumes Nous, or Reason, or artistic skill personified in his Demiurgus: whom he calls essentially good — meaning thereby that he is the regularising agent by whom order, method, and symmetry, are copied from the Ideas and partially realised among the intractable data of Necessity. Good is something which Plato in other works often talks about, but never determines: his language implies sometimes that he knows what it is, sometimes that he does not know. But so far as we can understand him, it means order, regularity, symmetry, proportion — by consequence, what 223is ascertainable and predictable.22 I will not say that Plato means this always and exclusively, by Good: but he seems to mean so in the Timæus. Evil is the reverse. Good or regularity is associated in his mind exclusively with rational agency. It can be produced, he assumes, only by a reason, or by some personal agent analogous to a reasonable and intelligent man. Whatever is not so produced, must be irregular or bad.

Process of demiurgic construction — The total Kosmos comes logically first, constructed on the model of the Αὐτοζῶον.

These are the fundamental ideas which Plato expands into a detailed Kosmology. The first application which he makes of them is, to construct the total Kosmos. The total is here the logical Prius, or anterior to the parts in his order of conception. The Kosmos is one vast and comprehensive animal: just as in physiological description, the leading or central idea is, that of the animal organism as a whole, to which each and all the parts are referred. The Kosmos is constructed by the Demiurgus according to the model of the Αὐτοζῶον,23 — (the Form or Idea of Animal — the eternal Generic or Self-Animal,) — which comprehends in itself the subordinate specific Ideas of different sorts of animals. This Generic Idea of Animal comprehended four of such specific Ideas: 1. The celestial race of animals, or Gods, who occupied the heavens. 2. Men. 3. Animals living in air — Birds. 4. Animals living on land or in water.24 In order that the Kosmos might approach near to its model the Self-animal, it was required to contain all these four species. As there was but one Self-Animal, so there could only be one Kosmos.

We see thus, that the primary and dominant idea, in Plato’s mind, is, not that of inorganic matter, but that of organised and animated matter — life or soul embodied. With him, biology comes before physics.

The body of the Kosmos was required to be both visible and tangible: it could not be visible without fire: it could not be tangible without something solid, nor solid without earth. But 224two things cannot be well put together by themselves, without a third to serve as a bond of connection: and that is the best bond which makes them One as much as possible. Geometrical proportion best accomplishes this object. But as both Fire and Earth were solids and not planes, no one mean proportional could be found between them. Two mean proportionals were necessary. Hence the Demiurgus interposed air and water, in such manner, that as fire is to air, so is air to water: and as air is to water, so is water to earth.25 Thus the four elements, composing the body of the Kosmos, were bound together in unity and friendship. Of each of the four, the entire total was used up in the construction: so that there remained nothing of them apart, to hurt the Kosmos from without, nor anything as raw material for a second Kosmos.26

225Body of the Kosmos, perfectly spherical — its rotations.

The Kosmos was constructed as a perfect sphere, rounded, because that figure both comprehends all other figures, and is, at the same time, the most perfect, and most like to itself.27 The Demiurgus made it perfectly smooth on the outside, for various reasons.28 First, it stood in no need of either eyes or ears, because there was nothing outside to be seen or heard. Next, it did not want organs of respiration, inasmuch as there was no outside air to be breathed:— nor nutritive and excrementary organs, because its own decay supplied it with nourishment, so that it was self-sufficing, being constructed as its own agent and its own patient.29 Moreover the Demiurgus did not furnish it with hands, because there was nothing for it either to grasp or repel — nor with legs, feet, or means of standing, because he assigned to it only one of the seven possible varieties of movement.30 He gave to it no other movement except that of rotation in a circle, in one and the same place: which is the sort of movement that belongs most to reason and intelligence, while it is impracticable to all other figures except the spherical.31

Soul of the Kosmos — its component ingredients — stretched from centre to circumference.

The Kosmos, one and only-begotten, was thus perfect as to its body, including all existent bodily material, — smooth, even, round, and equidistant from its centre to all points of the circumference.32 The Demiurgus put together at the same time its soul or mind; which 226he planted in the centre and stretched throughout its body in every direction, — so as not only to reach the circumference, but also to enclose and wrap it round externally. The soul, being intended to guide and govern the body, was formed of appropriate ingredients, three distinct ingredients mixed together: 1. The Same — The Identical — The indivisible, and unchangeable essence of Ideas. 2. The Different — The Plural — The divisible essence of bodies or of the elements. 3. A third compound, formed of both these ingredients melted into one. — These three ingredients — Same, Different, Same and Different in one, — were blended together in one compound, to form the soul of the Kosmos: though the Different was found intractable and hard to conciliate.33 The mixture was divided, and the portions blended together, according to a scale of harmonic numerical proportion complicated and difficult to follow.34 The soul of the Kosmos was thus harmonically constituted. Among its constituent elements, the Same, or Identity, is placed in an even and undivided rotation of the outer or sidereal sphere of the Kosmos, — while the Different, or Diversity, is distributed among the rotations, all oblique, of the seven interior or planetary spheres — that is, the five planets, Sun, and Moon. The outer sphere revolved towards the right: the interior spheres in an opposite direction towards the left. The rotatory force of the Same (of the outer Sphere) being not only one and undivided, but connected with and dependent upon the solid revolving axis which traverses the diameter of the Kosmos — is far greater than that of the divided spheres of the Different; which, while striving to revolve in an opposite direction, each by 227a movement of its own — are overpowered and carried along with the outer sphere, though the time of revolution, in the case of each, is more or less modified by its own inherent counter-moving force.35

In regard to the constitution of the kosmical soul, we must note, that as it is intended to know Same, Different, and Same and Different in one — so it must embody these three ingredients in its own nature: according to the received axiom. Like knows like — Like is known by like.36 Thus began, never to end, the rotatory movements of the living Kosmos or great Kosmical God. The invisible soul of the Kosmos, rooted at its centre and stretching from thence so as to pervade and enclose its visible body, circulates and communicates, though without voice or sound, throughout its own entire range, every impression of identity and of difference which it encounters either from essence ideal and indivisible, or from that which is sensible and divisible. Information is thus circulated, about the existing relations between all the separate parts and specialties.37 Reason and Science are propagated by the Circle of the Same: Sense and Opinion, by those of the Different. When these last-mentioned Circles are in right movement, the opinions circulated are true and trustworthy.

Regular or measured Time — began with the Kosmos.

With the rotations of the Kosmos, began the course of Time — years, months, days, &c. Anterior to the Kosmos, there was no time: no past, present, and future: no numerable or mensurable motion or change. The Ideas are eternal essences, without fluctuation or change: existing sub specie æternitatis, and having only a perpetual228 present, but no past or future.38 Along with them subsisted only the disorderly, immeasurable, movements of Chaos. The nearest approach which the Demiurgus could make in copying these Ideas, was, by assigning to the Kosmos an eternal and unchanging motion, marked and measured by the varying position of the heavenly bodies. For this purpose, the sun, moon, and planets, were distributed among the various portions of the circle of Different: while the fixed stars were placed in the Circle of the Same, or the outer Circle, revolving in one uniform rotation and in unaltered position in regard to each other. The interval of one day was marked by one revolution of this outer or most rational Circle:39 that of one month, by a revolution of the moon: that of one year, by a revolution of the sun. Among all these sidereal and planetary Gods the Earth was the first and oldest. It was packed close round the great axis which traversed the centre of the Kosmos, by the turning of which axis the outer circle of the Kosmos was made to revolve, generating night and day. The Earth regulated the movement of this great kosmical axis, and thus become the determining agent and guarantee of night and day.40

229Divine tenants of the Kosmos. Primary and Visible Gods — Stars and Heavenly Bodies.

It remained for the Demiurgus, — in order that the Kosmos might become a full copy of its model the Generic Animal or Idea of Animal, — to introduce into it those various species of animals which that Idea contained. He first peopled it with Gods: the eldest and earliest of whom was the Earth, planted in the centre as sentinel over night and day: next the fixed stars, formed for the most part of fire, and annexed to the circle of the Same or the exterior circle, so as to impart to it light and brilliancy. Each star was of spherical figure and had two motions, — one, of uniform rotation peculiar to itself, — the other, an uniform forward movement of translation, being carried along with the great outer circle in its general rotation round the axis of the Kosmos.41 It is thus that the sidereal orbs, animated beings eternal and divine, remained constantly turning round in the same relative position: while the sun, moon, and planets, belonging to the inner circles of the Different, and trying to revolve by their own effort in the opposite direction to the outer sphere, became irregular in their own velocities and variable in their relative positions.42 The complicated movements of these planetary bodies, alternately approaching and receding — together with their occultations and reappearances, full of alarming prognostic as to consequences — cannot be described without having at hand some diagrams or mechanical illustrations to refer to.43

230Secondary and generated Gods — Plato’s dictum respecting them. His acquiescence in tradition.

Such were all the primitive Gods visible and generated44 by the Demiurgus, to preside over and regulate the Kosmos. By them are generated, and from them are descended, the remaining Gods.

Respecting these remaining Gods, however, the Platonic Timæus holds a different language. Instead of speaking in his own name and delivering his own convictions, as he had done about the Demiurgus and the cosmical Gods — with the simple reservation, that such convictions could be proclaimed only as probable and not as demonstratively certain — he now descends to the Sokratic platform of confessed ignorance and incapacity. “The generation of these remaining Gods (he says) is a matter too great for me to understand and declare. I must trust to those who have spoken upon the subject before me — who were, as they themselves said, offspring of the Gods, and must therefore have well known their own fathers. It is impossible to mistrust the sons of the Gods. Their statements indeed are unsupported either by probabilities or by necessary demonstration; but since they here profess to be declaring family traditions, we must obey the law and believe.45 Thus then let it stand and be proclaimed, upon their authority, 231respecting the generation of the remaining Gods. The offspring of Uranus and Gæa were, Okeanus and Tethys: from whom sprang Phorkys, Kronus, Rhea, and those along with them. Kronus and Rhea had for offspring Zeus, Hêrê, and all these who are termed their brethren: from whom too, besides, we hear of other offspring. Thus were generated all the Gods, both those who always conspicuously revolve, and those who show themselves only when they please.”46

Remarks on Plato’s Canon of Belief.

The passage above cited serves to illustrate both Plato’s own canon of belief, and his position in regard to his countrymen. The question here is, about the Gods of tradition and of the popular faith: with the paternity and filiation ascribed to them, by Hesiod and the other poets, from whom Greeks of the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. learnt their Theogony.47 Plato was a man both competent and willing to strike out a physical theology of his own, but not to follow passively in the track of orthodox tradition. I have stated briefly what he has affirmed about the cosmical Gods (Earth, Stars, Sun, Planets) generated or constructed by the Demiurgus as portions or members of the Kosmos: their bodies, out of fire and other elements, — their souls out of the Forms or abstractions called Identity and Diversity; while the entire Kosmos is put together after the model of the Generic Idea or Form of Animal. All this, combined with supposed purposes, and fancies of arithmetical proportion dictating the proceedings of the Demiurgus, Plato does not hesitate to proclaim on his own authority and as his own belief — though he does not carry it farther than probability.

But while the feeling of spontaneous belief thus readily arises in Plato’s mind, following in the wake of his own constructive imagination and ethical or æsthetical sentiment (fingunt simul creduntque) — it does not so readily cleave to the theological dogmas in actual circulation around him. In the generation of Gods from Uranus and Gæa — which he as well as other Athenian youths must have learnt when they recited Hesiod with their schoolmasters — he can see neither proof nor probability:232 he can find no internal ground for belief.48 He declares himself incompetent: he will not undertake to affirm any thing upon his own judgment: the mystery is too dark for him to penetrate. Yet on the other hand, though it would be rash to affirm, it would be equally rash to deny. Nearly all around him are believers, at least as well satisfied with their creed as he was with the uncertified affirmations of his own Timæus. He cannot prove them to be wrong, except by appealing to an ethical or æsthetical sentiment which they do not share. Among the Gods said to be descended from Uranus and Gæa, were all those to whom public worship was paid in Greece, — to whom the genealogies of the heroic and sacred families were traced, — and by whom cities as well as individuals believed themselves to be protected in dangers, healed in epidemics, and enlightened on critical emergencies through seasonable revelations and prophecies. Against an established creed thus avouched, it was dangerous to raise any doubts. Moreover Plato could not have forgotten the fate of his master Sokrates;49 who was indicted both for not acknowledging the Gods whom the city acknowledged, and for introducing other new divine matters and persons. There could be no doubt that Plato was guilty on this latter count: prudence therefore rendered it the more incumbent on him to guard against being implicated in the former count also. Here then Plato formally abnegates his own self-judging power, and submits himself to orthodox authority. “It is impossible to doubt what we have learnt from witnesses, who declared themselves to be the offspring of the Gods, and who must of course have known their own family affairs. We must obey the law and believe.” In what proportion such submission, of reason to authority, embodied the sincere feeling of Pascal and 233Malebranche, or the irony of Bayle and Voltaire, we are unable to determine.50

Address and order of the Demiurgus to the generated Gods.

Having thus, during one short paragraph, proclaimed his deference, if not his adhesion, to inspired traditions, Plato again resumes the declaration of his own beliefs and his own book of Genesis, without any farther appeal to authority, and without any intimation that he is touching on mysteries too great for his reason. When these Gods, the visible as well as the invisible,51 had all been constructed or generated, he (or Timæus) tells us that the Demiurgus addressed them and informed them that they would be of immortal duration — not indeed in their own nature, but through his determination: that to complete the perfection of the newly-begotten Kosmos, there were three other distinct races of animals, all mortal, to be added: that he could not himself undertake the construction of these three, because they would thereby be rendered immortal, but that he confided such construction to them (the Gods): that he would himself supply, for the best of these three new races, an immortal element as guide and superintendent, and that they were to join along with it mortal and bodily accompaniments, to constitute men and animals; thus imitating the power which he had displayed in the generation of themselves.52

Preparations for the construction of man. Conjunction of three souls and one body.

After this address (which Plato puts into the first person, in Homeric manner), the Demiurgus compounded together, again and in the same bowl, the remnant of the same elements out of which he had formed the kosmical soul, but in perfection and purity greatly inferior. The total mass thus formed was distributed into souls equal in number to the stars. The Demiurgus234 placed each soul in a star of its own, carried it round thus in the kosmical rotation, and explained to it the destiny intended for all. For each alike there was to be an appointed hour of birth, and of conjunction with a body, as well as with two inferior sorts or varieties of soul or mind. From such conjunction would follow, as a necessary consequence, implanted sensibility and motive power, with all its accompaniments of pleasure, pain, desire, fear, anger, and such like. These were the irrational enemies, which the rational and immortal soul would have to controul and subdue, as a condition of just life. If it succeeded in the combat so as to live a good life, it would return after death to the abode of its own peculiar star. But if it failed, it would have a second birth into the inferior nature and body of a female: if, here also, it continued to be evil, it would be transferred after death to the body of some inferior animal. Such transmigration would be farther continued from animal to animal, until the rational soul should acquire thorough controul over the irrational and turbulent. When this was attained, the rational soul would be allowed to return to its original privilege and happiness, residing in its own peculiar star.53

It was thus that the Demiurgus confided to the recently-generated Gods the task of fabricating both mortal bodies, and mortal souls, to be joined with these immortal souls in their new stage of existence — and of guiding and governing the new mortal animal in the best manner, unless in so far as the latter should be the cause of mischief to himself. The Demiurgus decreed and proclaimed this beforehand, in order (says Plato) that he might not himself be the cause of any of the evil which might ensue54 to individual men.

235Proceedings of the generated Gods — they fabricate the cranium, as miniature of the Kosmos, with the rational soul rotating within it.

Accordingly the Gods, sons of the Demiurgus, entered upon the task, trying to imitate their father. Borrowing from the Kosmos portions of the four elements, with engagement that what was borrowed should one day be paid back, they glued them together, and fastened them by numerous minute invisible pegs into one body. Into this body, always decaying and requiring renovation, they introduced the immortal soul, with its double circular rotations — the Circles of the Same and of the Diverse: embodying it in the cranium, which was made spherical in exterior form like the Kosmos, and admitting within it no other motion but the rotatory. The head, the most divine portion of the human system, was made master; while the body was admitted only as subject and ministerial. The body was endowed with all the six varieties of motive power, forward, backwards — upward, downward — to the right, to the left.55 The phenomena of nutrition and sensation236 began. But all these irregular movements, and violent multifarious agitations, checked or disturbed the regular rotations of the immortal soul in the cranium, perverting the arithmetical proportion, and harmony belonging to them. The rotations of the Circles of Same and Diverse were made to convey false and foolish affirmation. The soul became utterly destitute of intelligence, on being first joined to the body, and for some time afterwards.56 But in the course of time the violence of these disturbing currents abates, so that the rotations of the Circles in the head can take place with more quiet and regularity. The man then becomes more and more intelligent. If subjected to good education and discipline, he will be made gradually sound and whole, free from corruption: but if he neglect this precaution, his life remains a lame one, and he returns back to Hades incomplete and unprofitable.57

The cranium is mounted on a tall body — six varieties of motion — organs of sense. Vision — Light.

The Gods, when they undertook the fabrication of the body, foresaw the inconvenience of allowing the head — with its intelligent rotations, and with the immortal soul enclosed in it — to roll along the ground, unable to get over a height, or out of a hollow.58 Accordingly they mounted it upon a tall body; with arms and legs as instruments of movement, support, and defence. They caused the movements to be generally directed forward and not backward; since front is more honourable and more commanding than rear. For the same reason, they placed the face, with the organs of sense, in the fore part of the head. Within the eyes, they planted that variety of fire which does not burn, but is called light, homogeneous with the light without. We are enabled to see in the daytime, because the light within our eyes pours out through the centre of them, and commingles with the light without. The two, being thus confounded together, transmit movements from every object which they touch, through the eye inward to the soul; and thus bring about the sensation of sight. At night no vision takes place: because the 237light from the interior of our eyes, even when it still comes out, finds no cognate light in the air without, and thus becomes extinguished in the darkness. All the light within the eye would thus have been lost, if the Gods had not provided a protection: they contrived the eyelids which drop and shut up the interior light within. This light, being prevented from egress, diffuses itself throughout the interior system, and tranquillises the movements within so as to bring on sleep: without dreams, if all the movements are quenched — with dreams, corresponding to the movements which remain if there are any such.59

Principal advantages of sight and hearing. Observations of the rotation of the Kosmos.

Such are the auxiliary causes (continues Plato), often mistaken by others for principal causes, which the Gods employed to bring about sight. In themselves, they have no regularity of action: for nothing can be regular in action without mind and intelligence.60 But the most important among all the advantages of sight is, that it enables us to observe and study the rotations of the Kosmos and of the sidereal and planetary bodies. It is the observed rotations of days, months, and years, which impart to us the ideas of time and number, and enable us to investigate the universe. Hence we derive philosophy, the greatest of all blessings. Hence too we learn to apply the celestial rotations as a rule and model to amend the rotations of intelligence in our 238own cranium — since the first are regular and unerring, while the second are disorderly and changeful.61 It was for the like purpose, in view to the promotion of philosophy, that the Gods gave us voice and hearing. Both discourse and musical harmony are essential for this purpose. Harmony and rhythm are presents to us, from the Muses, not, as men now employ them, for unreflecting pleasure and recreation — but for the same purpose of regulating and attuning the disorderly rotations of the soul, and of correcting the ungraceful and unmeasured movements natural to the body.62

The Kosmos is product of joint action of Reason and Necessity. The four visible and tangible elements are not primitive.

At this point of the exposition, the Platonic Timæus breaks off the thread, and takes up a new commencement. Thus far (he says) we have proceeded in explaining the part of Reason or Intelligence in the fabrication of the Kosmos. We must now explain the part of Necessity: for the genesis of the Kosmos results from co-operation of the two. By necessity (as has been said before) Plato means random, indeterminate, chaotic, pre-existent, spontaneity of movement or force: spontaneity (ἡ πλανωμένη αἰτία) upon which Reason works by persuasion up to a certain point, prevailing upon it to submit to some degree of fixity and regularity.63 Timæus had described the body of the Kosmos as being constructed by the Demiurgus out of the four elements; thus assuming fire, air, earth, water, as pre-existent. But he now corrects himself, and tells us that such assumption is unwarranted. We must (he remarks) give a better and fuller explanation of the Kosmos. No one of these four elements is either primordial, or permanently distinct and definite in itself.

The only primordial reality is, an indeterminate, all-recipient fundamentum: having no form or determination of its own, but capable of receiving any form or determination from without.

Forms or Ideas and Materia Prima — Forms of the Elements — Place, or Receptivity.

In the second explanation now given by Plato of the Kosmos and its genesis, he assumes this invisible fundamentum (which he had not assumed before) as “the mother 239or nurse of all generation”. He assumes, besides, the eternal Forms or Ideas, to act upon it and to bestow determination or quality. These forms fulfil the office of father: the offspring of the two is — the generated, concrete, visible, objects,64 imitations of the Forms or Ideas, begotten out of this mother. How the Ideas act upon the Materia Prima, Plato cannot well explain: but each Form stamps an imitation or copy of itself upon portions of the common Fundamentum.65

But do there really exist any such Forms or Ideas — as Fire per se, the Generic Fire — Water per se, the Generic Water, invisible and intangible?66 Or is this mere unfounded speech? Does there exist nothing really anywhere, beyond the visible objects which we see and touch?67

We must assume (says Plato, after a certain brief argument which he himself does not regard as quite complete) the Forms or Ideas of Fire, Air, Water, Earth, as distinct and self-existent, eternal, indestructible, unchangeable — neither visible nor tangible, but apprehended by Reason or Intellect alone — neither receiving anything else from without, nor themselves moving to anything else. Distinct from these — images of these, and bearing the same name — are the sensible objects called Fire, Water, &c. — objects of sense and opinion — always in a state of transition — generated and destroyed, but always generated in some place and destroyed out of some place. There is to be 240assumed, besides, distinct from the two preceding — as a third fundamentum — the place or receptacle in which these images are localised, generated, and nursed up. This place, or formless primitive receptivity, is indestructible, but out of all reach of sense, and difficult to believe in, inasmuch as it is only accessible by a spurious sort of ratiocination.68

Primordial Chaos — Effect of intervention by the Demiurgus.

Anterior to the construction of the Kosmos, the Forms or Ideas of the four elements had already begun to act upon this primitive recipient or receptacle, but in a confused and irregular way. Neither of the four could impress itself in a special and definite manner: there were some vestiges of each, but each was incomplete: all were in stir and agitation, yet without any measure or fixed rule. Thick and heavy, however, were tending to separate from thin and light, and each particle thus tending to occupy a place of its own.69 In this condition (the primordial moving chaos of the poets and earlier philosophers), things were found by the Demiurgus, when he undertook to construct the Kosmos. There was no ready made Fire, Water, &c. (as Plato had assumed at the opening of the Timæus), but an agitated imbroglio of all, with the portions tending to separate from each other, and to agglomerate each in a place of its own. The Demiurgus brought these four elements out of confusion into definite bodies and regular movements. He gave to each a body, constructed upon the most beautiful proportions of arithmetic and geometry, as far as this was possible.70

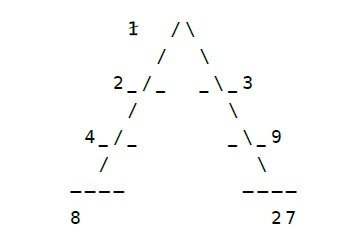

Geometrical theory of the elements — fundamental triangles — regular solids.

Respecting such proportions, the theory which Plato here lays out is admitted by himself to be a novel one; but it is doubtless borrowed, with more or less modification, from the Pythagoreans. Every solid body is circumscribed241 by plane surfaces: every plane surface is composed of triangles: all triangles are generated out of two — the right-angled isoskeles triangle — and the right-angled scalene or oblong triangle. Of this oblong there are infinite varieties: but the most beautiful is a right-angled triangle, having the hypotenuse twice as long as the lesser of the two other sides.71 From this sort of oblong triangle are generated the tetrahedron or pyramid — the octahedron — and the eikosihedron: from the equilateral triangle is generated the cube. The cube, as the most stable and solid, was assigned by the Demiurgus for the fundamental structure of earth: the pyramid for that of fire: the octahedron for that of air: the eikosihedron for that of water. The purpose was that the four should be in continuous geometrical proportion: as Fire to Air, so Air to Water: as Air to Water, so Water to Earth. Lastly, the Dodekahedron was assigned as the basis of structure for the spherical Kosmos itself or universe.72 Upon this arrangement each of the three elements — fire, water, air — passes into the other; being generated from the same radical triangle. But earth does not pass into either of the three (nor either of these into earth), being generated from a different radical triangle. The pyramid, as thin, sharp, and cutting, was assigned to fire 242as the quickest and most piercing of the four elements: the cube as most solid and difficult to move, was allotted to earth, the stationary element. Fire was composed of pyramids of different size, yet each too small to be visible by itself, and becoming visible only when grouped together in masses: the earth was composed of cubes of different size, each invisible from smallness: the other elements in like manner, each from its respective solid,73 in exact proportion and harmony, as far as Necessity could be persuaded to tolerate. All the five regular solids were thus employed in the configuration and structure of the Kosmos.74

Such was the mode of formation of the four so-called elemental bodies.75 Of each of the four, there are diverse species or varieties: and that which distinguishes one variety of the same element from another variety is, that the constituent triangles, though all similar, are of different magnitudes. The diversity of these combinations, though the primary triangles are similar, is infinite: the student of Nature must follow it out, to obtain any probable result.76

Varieties of each element.

Plato next enumerates the several varieties of each element — fire, water, earth.77 He then proceeds to mention the attributes, properties, affections, &c., of each: which he characterises as essentially relative to a sentient Subject: nothing being absolute except the constituent geometrical figures. You cannot describe these attributes (he says) without assuming (what has not yet been described) the sensitive243 or mortal soul, to which they are relative.78 Assuming this provisionally, Plato gives account of Hot and Cold, Hard and Soft, Heavy and Light, Rough and Smooth, &c.79 Then he describes, first, the sensations of pleasure and pain, common to the whole body — next those of the special senses, sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch.80 These descriptions are very curious and interesting. I am compelled to pass them over by want of space, and shall proceed to the statements respecting the two mortal souls and the containing organism — which belong to a vein more analogous to that of the other Platonic dialogues.

Construction of man imposed by the Demiurgus upon the secondary Gods. Triple Soul. Distribution thereof in the body.

The Demiurgus, after having constructed the entire Kosmos, together with the generated Gods, as well as Necessity would permit — imposed upon these Gods the task of constructing Man: the second best of the four varieties of animals whom he considered it necessary to include in the Kosmos. He furnished to them as a basis an immortal rational soul (diluted remnant 244from the soul of the Kosmos); with which they were directed to combine two mortal souls and a body.81 They executed their task as well as the conditions of the problem admitted. They were obliged to include in the mortal souls pleasure and pain, audacity and fear, anger, hope, appetite, sensation, &c., with all the concomitant mischiefs. By such uncongenial adjuncts the immortal rational soul was unavoidably defiled. The constructing Gods however took care to defile it as little as possible.82 They reserved the head as a separate abode for the immortal soul: planting the mortal soul apart from it in the trunk, and establishing the neck as an isthmus of separation between the two. Again the mortal soul was itself not single but double: including two divisions, a better and a worse. The Gods kept the two parts separate; placing the better portion in the thoracic cavity nearer to the head, and the worse portion lower down, in the abdominal cavity: the two being divided from each other by the diaphragm, built across the body as a wall of partition: just as in a dwelling-house, the apartments of the women are separated from those of the men. Above the diaphragm and near to the neck, was planted the energetic, courageous, contentious, soul; so placed as to receive orders easily from the head, and to aid the rational soul in keeping under constraint the mutinous soul of appetite, which was planted below the diaphragm.83 The immortal soul84 was fastened or anchored in the brain, the two mortal souls in the line of the spinal marrow continuous with the brain: which line thus formed the thread of connection between the three. The heart was established as an outer fortress for the exercise of influence by the immortal soul over the other two. It was at the same time made the initial point of the veins, the fountain from whence the current of blood proceeded to pass forcibly through the veins round to all parts of the body. The purpose of this arrangement is, that when the rational soul denounces some proceeding as wrong (either on the part of others without, or in the appetitive soul within), 245it may stimulate an ebullition of anger in the heart, and may transmit from thence its exhortations and threats through the many small blood channels to all the sensitive parts of the body: which may thus be rendered obedient everywhere to the orders of our better nature.85

Functions of the heart and lungs. Thoracic soul.

In such ebullitions of anger, as well as in moments of imminent danger, the heart leaps violently, becoming overheated and distended by excess of fire. The Gods foresaw this, and provided a safeguard against it by placing the lungs close at hand with the wind-pipe and trachea. The lungs were constructed soft and full of internal pores and cavities like a sponge; without any blood,86 — but receiving, instead of blood, both the air inspired through the trachea, and the water swallowed to quench thirst. Being thus always cool, and soft like a cushion, the lungs received and deadened the violent beating and leaping of the heart; at the same time that they cooled down its excessive heat, and rendered it a more equable minister for the orders of reason.87

Abdominal Soul — difficulty of controuling it — functions of the liver.

The third or lowest soul, of appetite and nutrition, was placed between the diaphragm and the navel. This region of the body was set apart like a manger for containing necessary food: and the appetitive soul was tied up to it like a wild beast; indispensable indeed for the continuance of the race, yet a troublesome adjunct, and therefore placed afar off, in order that its bellowings might disturb as little as possible the deliberations of the rational soul in the cranium, for the good of the whole. The Gods knew that this appetitive soul would never listen to reason, and that it must be kept under subjection altogether by the influence of phantoms and imagery. They provided an agency for this purpose in the liver, which they placed close upon the abode of the appetitive soul.88 They made the liver compact, smooth, and 246brilliant, like a mirror reflecting images:— moreover, both sweet and bitter on occasions. The thoughts of the rational soul were thus brought within view of the appetitive soul, in the form of phantoms or images exhibited on the mirror of the liver. When the rational soul is displeased, not only images corresponding to this feeling are impressed, but the bitter properties of the liver are all called forth. It becomes crumpled, discoloured, dark and rough; the gall bladder is compressed; the veins carrying the blood are blocked up, and pain as well as sickness arise. On the contrary, when the rational soul is satisfied, so as to send forth mild and complacent inspirations, — all this bitterness of the liver is tranquillised, and all its native sweetness called forth. The whole structure becomes straight and smooth; and the images impressed upon it are rendered propitious. It is thus through the liver, and by means of these images, that the rational soul maintains its ascendancy over the appetitive soul; either to terrify and subdue, or to comfort and encourage it.89

The liver is made the seat of the prophetic agency. Function of the spleen.

Moreover, the liver was made to serve another purpose. It was selected as the seat of the prophetic agency; which the Gods considered to be indispensable, as a refuge and aid for the irrational department of man. Though this portion of the soul had no concern with sense or reason, they would not shut it out altogether from some glimpse of truth. The revelations of prophecy were accordingly signified on the liver, for the instruction and within the easy view of the appetitive soul: and chiefly at periods when the functions of the rational soul are suspended — either during sleep, or disease, or fits of temporary ecstasy. For no man in his perfect senses comes under the influence of a genuine prophetic inspiration. Sense and intelligence are often required to interpret prophecies, and to determine what is meant by dreams or signs or prognostics of other kinds: but such revelations are received by men destitute of sense. To receive them, is the business of one class of men: to interpret them, that of another. It is a grave mistake, though often committed, to confound the two. It was in order to furnish prophecy to man, therefore, that 247the Gods devised both the structure and the place of the liver. During life, the prophetic indications are clearly marked upon it: but after death they become obscure and hard to decipher.90

The spleen was placed near the liver, corresponding to it on the left side, in order to take off from it any impure or excessive accretions or accumulations, and thus to preserve it clean and pure.91

Such was the distribution of the one immortal and the two mortal souls, and such the purposes by which it was dictated. We cannot indeed (says Plato) proclaim this with full assurance as truth, unless the Gods would confirm our declarations. We must take the risk of affirming what appears to us probable — and we shall proceed with this risk yet further.92 The following is the plan and calculation according to which it was becoming that our remaining bodily frame should be put together.

Length of the intestinal canal, in order that food might not be frequently needed.

The Gods foresaw that we should be intemperate in our appetite for food and drink, and that we should thus bring upon ourselves many diseases injurious to life. To mitigate this mischief, they provided us with a great length of intestinal canal, but twisted it round so as to occupy but a small space, in the belly. All the food which we introduce remains thus a long time within us, before it passes away. A greater interval elapses before we need fresh supplies of food. If the food passed away speedily, so that we were constantly obliged to renew it, and were therefore always eating — the human race would be utterly destitute of intelligence and philosophy. They would be beyond the controul of the rational soul.93

Bone — Flesh — Marrow.

Bone and flesh come next to be explained. Both of them derive their origin from the spinal marrow: in which the bonds of life are fastened, and soul is linked with body — the root of the human race. The origin of the spinal marrow itself is special and exceptional. Among the triangles 248employed in the construction of all the four elements, the Gods singled out the very best of each sort. Those selected were combined harmoniously with each other, and employed in the formation of the spinal marrow, as the universal seed ground (πανσπερμίαν) for all the human race. In this marrow the Gods planted the different sorts of souls; distributing and accommodating the figure of each portion of marrow to the requirements of each different soul. For that portion (called the encephalon, as being contained in the head) which was destined to receive the immortal soul, they employed the spherical figure and none other: for the remaining portion, wherein the mortal soul was to be received, they employed a mixture of the spherical and the oblong. All of it together was called by the same name marrow, covered and protected by one continuous bony case, and established as the holding ground to fasten the whole extent of soul with the whole extent of body.94

Nails — Mouth — Teeth. Plants produced for nutrition of man.

Plato next explains the construction of ligaments and flesh — of the mouth, tongue, teeth, and lips: of hair and nails.95 These last were produced with a long-sighted providence: for the Gods foresaw that the lower animals would be produced from the degeneration of man, and that to them nails and claws would be absolutely indispensable: accordingly, a sketch or rudiment of nails was introduced into the earliest organisation of man.96 Nutrition being indispensable to man, the Gods produced for this purpose plants (trees, shrubs, herbs, &c.) — with a nature cognate to that of man, but having only the lowest of the three human souls.97 They then cut ducts and veins throughout the human body, in directions appropriate for distributing the nutriment everywhere. They provided proper structures (here curiously described) for digestion, inspiration, and expiration.98 The constituent triangles within the body, when young and fresh, overpower the triangles, older and weaker, contained in the nutritive matters swallowed, and then appropriate part of them to the support and growth of the body: in old age, the triangles within are themselves overpowered, and the body decays. When the fastenings, 249whereby the triangles in the spinal marrow have been fitted together, are worn out and give way, they let go the fastenings of the soul also. The soul, when thus released in a natural way, flies away with delight. Death in this manner is pleasurable: though it is distressing, when brought on violently, by disease or wounds.99

General view of Diseases and their Causes.

Here Plato passes into a general survey of diseases and the proper treatment of them. “As to the source from whence diseases arise (he says) this is a matter evident to every one. They arise from unnatural excess, deficiency, or displacement, of some one or more of the four elements (fire, air, water, earth) which go to compose the body.”100 If the element in excess be fire, heat and continuous fever are produced: if air, the fever comes on alternate days: if water (a duller element), it is a tertian fever: if earth, it is a quartan — since earth is the dullest and most sluggish of the four.101

Diseases of mind — wickedness is a disease — no man is voluntarily wicked.

Having dwelt at considerable length on the distempers of the body, the Platonic Timæus next examines those of the soul, which proceed from the condition of the body.102 The generic expression for all distemper of the soul is, irrationality — unreason — absence of reason or intelligence. Of this there are two sorts — madness and ignorance. Intense pleasures and pains are the gravest cause of madness.103 A man under either of these two influences — either grasping at the former, or running away from the latter, out of season — can neither see nor hear any thing rightly. He is at that moment mad and incapable of using his reason. When the flow of sperm round his marrow is overcharged and violent, so as to produce desires with intense throes of uneasiness beforehand and intense pleasure when satisfaction arrives, — his soul is really distempered and irrational, through the ascendancy of his body. Yet such a man is erroneously looked upon in general not as distempered, but as wicked voluntarily,250 of his own accord. The truth is, that sexual intemperance is a disorder of the soul arising from an abundant flow of one kind of liquid in the body, combined with thin bones or deficiency in the solids. And nearly all those intemperate habits which are urged as matters of reproach against a man — as if he were bad willingly, — are urged only from the assumption of an erroneous hypothesis. No man is bad willingly, but only from some evil habit of body and from wrong or perverting treatment in youth; which is hostile to his nature, and comes upon him against his own will.104

Badness of mind arises from body.

Again, not merely by way of pleasures, but by way of pains also, the body operates to entail evil or wickedness on the soul. When acid or salt phlegm — when bitter and bilious humours — come to spread through the body, remaining pent up therein, without being able to escape by exhalation, — the effluvia which ought to have been exhaled from them become confounded with the rotation of the soul, producing in it all manner of distempers. These effluvia attack all the three different seats of the soul, occasioning great diversity of mischiefs according to the part attacked — irascibility, despondency, rashness, cowardice, forgetfulness, stupidity. Such bad constitution of the body serves as the foundation of ulterior mischief. And when there supervene, in addition, bad systems of government and bad social maxims, without any means of correction furnished to youth through good social instruction — it is from these two combined causes, both of them against our own will, that all of us who are wicked become wicked. Parents and teachers are more in fault than children and pupils. We must do our best to arrange the bringing up, the habits, and the instruction, so as to eschew evil and attain good.105

Preservative and healing agencies against disease — well-regulated exercise, of mind and body proportionally.

After thus describing the causes of corruption, both in body and mind, Plato adverts to the preservative and corrective agencies applicable to them. Between the one and the other, constant proportion and symmetry must be imperatively maintained. When the one is strong, and the other weak, nothing but mischief can ensue.106 Mind must not be exercised alone, to the 251exclusion of body; nor body alone, without mind. Each must be exercised, so as to maintain adequate reaction and equilibrium against the other.107 We ought never to let the body be at rest: we must keep up within it a perpetual succession of moderate shocks, so that it may make suitable resistance against foreign causes of movement, internal and external.108 The best of all movements is, that which is both in itself and made by itself: analogous to the self-continuing rotation both of the Kosmos and of the rational soul in our cranium.109 Movement in itself, but by an external agent, is less good. The worst of all is, movement neither in itself nor by itself. Among these three sorts of movement, the first is, Gymnastic: the second, propulsion backwards and forwards in a swing, gestation in a carriage: the third is, purgation or medicinal disturbance.110 This last is never to be employed, except in extreme emergencies.

Treatment proper for mind alone, apart from body — supremacy of the rational soul must be cultivated.

We must now indicate the treatment necessary for mind alone, apart from body. It has been already stated, that there are in each of us three souls, or three distinct varieties of soul; each having its own separate place and special movements. Of these three, that which is most exercised must necessarily become the strongest: that which is left unexercised, unmoved, at rest or in indolence, — will become the weakest. The object to be aimed at is, that all three shall be exercised in harmony or proportion with each other. Respecting the soul in our head, the grandest and most commanding of the three, we must bear in mind that it is this which the Gods have assigned to each man as his own special Dæmon or presiding Genius. Dwelling as it does in the highest region of the body, it marks us and links us as akin with heaven — as a celestial and not a terrestrial plant, having root in heaven and not in earth. It is this encephalic or head-soul, which, connected with and suspended from the divine soul of the Kosmos, keeps our whole 252body in its erect attitude. Now if a man neglects this soul, directing all his favour and development towards the two others (the energetic or the appetitive), — all his judgments will infallibly become mortal and transient, and he himself will be degraded into a mortal being, as far as it is possible for man to become so. But if he devotes himself to study and meditation on truth, exercising the encephalic soul more than the other two — he will assuredly, if he seizes truth,111 have his mind filled with immortal and divine judgments, and will become himself immortal, as far as human nature admits of it. Cultivating as he does systematically the divine element within him, and having his in-dwelling Genius decorated as perfectly as possible, he will be eminently well-inspired or happy.112

We must study and understand the rotations of the Kosmos — this is the way to amend the rotations of the rational soul.

The mode of cultivating or developing each soul is the same — to assign to each the nourishment and the movement which is suitable to it. Now the movements which are kindred and congenial to our divine encephalic soul, are — the rotations of the Kosmos and the intellections traversing the Kosmical soul. It is these that we ought to follow and study. By learning and embracing in our minds the rotations and proportions of the Kosmos, we shall assimilate the comprehending subject to the comprehended object, and shall rectify that derangement of our own intra-cranial rotations, which was entailed upon us by our birth into a body. By such assimilation, we shall attain the perfection of the life allotted to us, both at present and for the future.113

Construction of women, birds, quadrupeds, fishes, &c., all from the degradation of primitive man.

We have thus — says the Platonic Timæus in approaching his conclusion — gone through all those matters which we promised at the beginning, from the first construction of the Kosmos to the genesis of man. We must now devote a few words to the other animals. 253All of these derive their origin from man, by successive degradations. The first transition is from man into woman. Men whose lives had been characterised by cowardice or injustice, were after death and in their second birth born again as women. It was then that the Gods planted in us the sexual impulse, reconstructing the bodily organism with suitable adjustment, on the double pattern, male and female.114

Such was the genesis of women, by a partial transformation and diversification of the male structure.

We next come to birds; who are likewise a degraded birth or formation, derived from one peculiar mode of degeneracy in man: hair being transmuted into feathers and wings. Birds were formed from the harmless, but light, airy, and superficial men; who, though carrying their minds aloft to the study of kosmical phenomena, studied them by visual observation and not by reason, foolishly imagining that they had discovered the way of reaching truth.115

The more brutal land animals proceeded from men totally destitute of philosophy, who neither looked up to the heavens nor cared for celestial objects: from men making no use whatever of the rotations of their encephalic soul, but following exclusively the guidance of the lower soul in the trunk. Through such tastes and occupations, both their heads and their anterior limbs became dragged down to the earth by the force of affinity. Moreover, when the rotations of the encephalic soul, from want of exercise, became slackened and fell into desuetude, the round form of the cranium was lost, and converted into an oblong or some other form. These men thus degenerated into quadrupeds and multipeds: the Gods furnishing a greater number of feet in proportion to the stupidity of each, in order that its approximations to earth might be multiplied. To some of the more stupid, however, the Gods gave no feet nor limbs at all; constraining them to drag the whole length of their bodies along the ground, and to become Reptiles.116

254Out of the most stupid and senseless of mankind, by still greater degeneracy, the Gods formed Fishes or Aquatic Animals:— the fourth and lowest genus, after Men, Birds, Land-Animals. This race of beings, from their extreme want of mind, were not considered worthy to live on earth, or to respire thin and pure air. They were condemned to respire nothing but deep and turbid water, many of them, as oysters, and other descriptions of shellfish, being fixed down at the lowest depth or bottom.117

It is by such transitions (concludes the Platonic Timæus) that the different races of animals passed originally, and still continue to pass, into each other. The interchange is determined by the acquisition or loss of reason or irrationality.118

Large range of topics introduced in the Timæus.

The vast range of topics, included in this curious exposition, is truly remarkable: Kosmogony or Theogony, First Philosophy, Physics (resting upon Geometry and Arithmetic), Zoology, Physiology, Anatomy, Pathology, Therapeutics, mental as well as physical. Of all these, I have not been able to furnish more than scanty illustrations; but the whole are well worthy of study, as the conjectures of a great and ingenious mind in the existing state of knowledge and belief among the Greeks: and all the more worthy, because they form in many respects a striking contrast with the points of view prevalent in more recent times.

The Demiurgus of the Platonic Timæus — how conceived by other philosophers of the same century.

The position and functions of the Demiurgus, in the Timæus, form a peculiar phase in Grecian Philosophy, and even in the doctrine of Plato himself: for the theology and kosmology of the Timæus differ considerably from what we read in the Phædrus, Politikus, Republic, Leges, &c. The Demiurgus is presented in Timæus as a personal agent, pre-kosmical and extra-kosmical: but he appears only as initiating; he begets or fabricates, once for all, a most beautiful 255Kosmos (employing all the available material, so that nothing more could afterwards be added). The Kosmos having body and soul, is itself a God, but with many separate Gods resident within it, or attached to it. The Demiurgus then retires, leaving it to be peopled and administered by the Gods thus generated, or by its own soul. His acting and speaking is recounted in the manner of the ancient mythes: and many critics, ancient as well as modern, have supposed that he is intended by Plato only as a mythical personification of the Idea Boni: the construction described being only an ideal process, like the generation of a geometrical figure.119 Whatever may have been Plato’s own intention, in this last sense his hypothesis was interpreted by his immediate successors, Speusippus and Xenokrates, as well as by Eudêmus.120 Aristotle in his comments upon Plato takes little notice of the Demiurgus: the hypothesis (of a distinct personal constructive agent) did not fit into his principia of the Kosmos, and he probably ranked it among those mythical modes of philosophising which he expressly pronounces to be unworthy of serious criticism.121 Various succeeding philosophers 256also, especially the Stoics, while they insisted much upon Providence, conceived this as residing in the Kosmos itself, and in the divine intra-kosmical agencies.

Adopted and welcomed by the Alexandrine Jews, as a parallel to the Mosaic Genesis.

But though the idea of a pre-kosmic Demiurgus found little favour among the Grecian schools of philosophy, before the Christian era — it was greatly welcomed among the Hellenising Jews at Alexandria, from Aristobulus (about B. C. 150) down to Philo. It formed the suitable point of conjunction, between Hellenic and Judaic speculation. The marked distinction drawn by Plato between the Demiurgus, and the constructed or generated Kosmos, with its in-dwelling Gods — provided a suitable place for the Supreme God of the Jews, degrading the Pagan Gods in comparison. The Timæus was compared with the book of Genesis, from which it was even affirmed that Plato had copied. He received the denomination of the atticising Moses: Moses writing in Attic Greek.122 It was thus that the Platonic Timæus became the medium of transition, from the Polytheistic theology which served as philosophy among 257the early ages of Greece, to the omnipotent Monotheism to which philosophy became subordinated after the Christian era.

Physiology of the Platonic Timæus — subordinate to Plato’s views of ethical teleology. Triple soul — each soul at once material and mental.

Of the vast outline sketched in the Timæus, no part illustrates better the point of view of the author, than what is said about human anatomy and physiology. The human body is conceived altogether as subservient to an ethical and æsthetical teleology: it is (like the Praxitelean statue of Eros123) a work adapted to an archetypal model in Plato’s own heart — his emotions, preferences, antipathies.124 The leading idea in his mind is, What purposes would be most suitable to the presumed character of the Demiurgus, and to those generated Gods who are assumed to act as his ministers? The purposes which Plato ascribes, both to the one and to the others, emanate from his own feelings: they are such as he would himself have aimed at accomplishing, if he had possessed demiurgic power: just as the Republic describes the principles on which he would have constituted a Commonwealth, had he been lawgiver or Oekist. His inventive fancy depicts the interior structure, both of the great Kosmos and of its little human miniature, in a way corresponding to these sublime purposes. The three souls, each with its appropriate place and functions, form the cardinal principle of the organism:125 the unity of which is maintained by 258the spinal marrow in continuity with, the brain; all the three souls having their roots in different parts of this continuous line. Neither of these three souls is immaterial, in the sense which that word now bears: even the encephalic rational soul — the most exalted in function, and commander of the other two — has its own extension and rotatory motion: as the kosmical soul has also, though yet more exalted in its endowments. All these souls have material properties, and are implicated essentially with other material agents:126 all are at once material and mental. The encephalic or rational soul has its share in material properties, while the abdominal or appetitive soul also has its share in mental properties: even the liver has for its function to exhibit images impressed by the rational soul, and to serve as the theatre of prophetic representations.127

Triplicity of the soul — espoused afterwards by Galen.

The Platonic doctrine, of three souls in one organism, derives a peculiar interest from the earnest way in which it is espoused afterwards by Galen. This last author represents Plato as agreeing in main doctrines with Hippokrates. He has composed nine distinct Dissertations or Books, for the purpose of upholding their joint doctrines. But the agreement which he shows between Hippokrates and Plato is very vague, and his own agreement with Plato is rather ethical than physiological. What is the essence of the three souls, and whether they are immortal or not, Galen leaves undecided:128 but that there must be three distinct souls in each human body, and that the supposition of one soul only is an absurdity — he considers Plato to have positively demonstrated. 259He rejects the doctrine of Aristotle, Theophrastus, Poseidonius, and others, who acknowledged only one soul, lodged in the heart, but with distinct co-existent powers.129

Admiration of Galen for Plato — his agreement with Plato, and his dissension from Plato — his improved physiology.

So far Galen concurs with Plato. But he connects this triplicity of soul with a physiological theory of his own, which he professes to derive from, or at least to hold in common with, Hippokrates and Plato. Galen recognises three ἀρχὰς — principia, beginnings, originating and governing organs — in the body: the brain, which is the origin of all the nerves, both of sensation and motion: the heart, the origin of the arteries: the liver, the sanguifacient organ, and the origin of the veins which distribute nourishment to all parts of the body. These three are respectively the organs of the rational, the energetic, and the appetitive soul.130

The Galenian theory here propounded (which held its place in physiology until Harvey’s great discovery of the circulation of 260the blood in the seventeenth century), though proved by fuller investigation to be altogether erroneous as to the liver — and partially erroneous as to the heart — is nevertheless made by its author to rest upon plausible reasons, as well as upon many anatomical facts, and results of experiments on the animal body, by tying or cutting nerves and arteries.131 Its resemblance with the Platonic theory is altogether superficial: while the Galenian reasoning, so far from resembling the Platonic, stands in striking contrast with it. Anxious as Galen is to extol Plato, his manner of expounding and defending the Platonic thesis is such as to mark the scientific progress realised during the five centuries intervening between the two. Plato himself, in the Timæus, displays little interest or curiosity about the facts of physiology: the connecting principles, whereby he explains to himself the mechanism of the organs as known by ordinary experience, are altogether psychological, ethical, teleological. In the praise which Galen, with his very superior knowledge of the human organism, bestows upon the Timæus, he unconsciously substitutes a new doctrine of his own, differing materially from that of Plato.

Physiology and pathology of Plato — compared with that of Aristotle and the Hippokratic treatises.