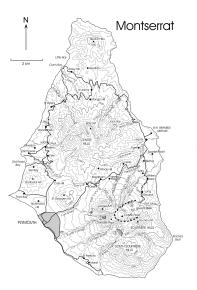

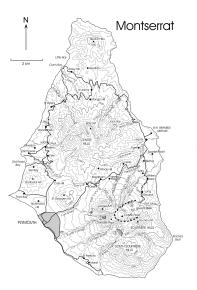

Fig. 1: Map of Montserrat (click on map to see larger version)

The Soufriere Hills Volcano on the British Dependent Territory of Montserrat entered an eruptive state on 18 July 1995.1 The eruption also reopened a new chapter in the history of immigration to the United Kingdom (UK) by Caribbean nationals. The impasse, it will be recalled was most significantly marked by the coming into force of The Commonwealth Immigrants Act, 1962.2

This paper, while retracing the history of British efforts to progressively exclude Caribbean nationals from entry into the UK since 1962, will illustrate that this policy of exclusion continued to inform the actions of British decision makers who have responsibility for the welfare and protection of a people called Montserratians.3

A number of sources will be cited to support the view that immigration control in the UK is like "no other country in the world" in its focus on the "exclusion of one particular category of people",4 but will not dwell on this issue. The primary purpose here is to show that not only did Montserratians fall into this category, but also that a number of measures were implemented which maintained the practice of their exclusion from the UK when they needed a place of refuge between 1995 to 2000. The walls of the 1962 Act and the subsequent measures taken up to 1988 to deny entry into the UK to Commonwealth Caribbean nationals were maintained against the approximately 10,000 people of Montserrat despite the volcanic peril facing a people who have remained loyal British colonists since 1662. Remarkably, even while the volcano continued to erupt only conditional entry was granted to these unlikely refugees and the future status of a people who call themselves Montserratians was not clarified until 2002.

At a time when they were acknowledged to be facing clear and present danger from an act of nature, Montserratians received temporary protected status and British paid packages, which served to disperse them to neighbouring Caribbean islands, the United States and Canada (as opposed to the UK). Faced with strong regional dissent, Montserratians were granted at one stage only qualified leave to remain in the UK.

A necessary precondition of this discourse is to retrace a brief history of Montserrat and that island's treatment as a dependency whose citizens continue to be nationals of the UK, albeit more in the sense of a third class status.5

Democratic governance remains in force in Montserrat with Her Majesty the Queen, Elizabeth II as Head of State. Her representative to Montserrat is a governor. The governor is President of the island's Executive over which he exercises veto power.

He also has responsibility for the civil service, defence, internal security, external affairs and the judiciary.

His reserve powers by the Montserrat Constitution Order 1990 "provided that the question whether or not the Governor has in any matter complied with any such instructions shall not be enquired into by any court."6 A Montserratian may travel on a standard United Kingdom passport issued by the local authority as provided for the main purpose of implementing a certain element of the British Nationality which will be discussed later.

In 1632, history records the island's first permanent settlement by Europeans. They were the Irish, under the leadership of Sir Thomas Warner, fleeing the wrath of Oliver Cromwell in Europe.7 Montserratians still celebrate an annual St Patrick's Day.8 When the British-backed West Indies Federation failed in 1962,9 Montserrat opted to remain a British colony and its people have consistently maintained their allegiance to the crown. There was however a period between 1978-1990 when the then charismatic Chief Minister John Osborne pursued his dream for an independent Montserrat.10 A lucrative lime and cotton export industry from 1930-60 overtaken by its niche upmarket tourism product thereafter produced a viable Montserrat economy. By 1981 the island was in a position to refuse UK budgetary aid. The tourism dollar in addition to strong migrant remittances generated economic buoyancy amounting to a budget surplus by 1995.11 It should be noted here that the UK's anti-family re-union policy which predominated in the 1960s encouraged the investment in large family homes in Montserrat for the many who prepared for the end of their sojourn in the UK. This was in keeping with a pattern common to the experience of immigrants from the islands.12 The self-repatriation exercise began in earnest around 1994 so that the future of hundreds, if not thousands, of Montserratians has been forever altered by the eruption of the Soufriere Hills Volcano in 1995.13

The volcanic eruption in Montserrat14 has been compared to the 1902 Mount Pelee disaster in Martinique except that the former is being dismantled by a prolonged, as opposed to an explosive, event since 18 July 1995.15

Montserrat's Deputy Chief Minister, in a Report to the 18th Conference of CARICOM Heads of Government described the situation thus:

Nine [of 13] villages have been consumed by lava. The island's people have relocated into an area of sparse infrastructure leaving behind their hospital, commercial sector, telecommunications service, petroleum installations, schools, library, banks, administration centre and other government ministry buildings. The private sector, which operated principally from the capital, Plymouth, was decimated.16

It is assumed that a full accounting of the volcanic activity, which has destroyed or rendered two-thirds of this 39.5 Sq. ml. island inhabitable is not necessary for the purposes of this paper. Table A, which is set down at Annex II to this document, presents a chronology of events relative to the response to the situation in Montserrat from 1995 to 1997.17 The data indicates that a number of voluntary evacuations to neighbouring islands predominates the scene up to April 1996. Up to 17 September 1997, Montserratians were permitted to come to the UK only for a limited time period in an environment that "if there were an [official] emergency evacuation Montserratians would not know what to do" or where to go.18 The governor confirmed during the course of his testimony to the International Development Committee that "the plan [for off-island evacuation] was never made public."19

As of 18 July 1995 the regional response mechanism was activated to deal with the Montserrat crisis.20 A variety of donors including the Japanese government were involved in the emergency provision of food, water and other critical medical and other supplies to assist the people during what was an unprecedented crisis in the region.21 The full impact of the regional response to the situation in Montserrat will be discussed further in the context of the immigration and nationality status of Montserratians and the polite insistence by the region that the United Kingdom accept responsibility for its people fleeing the erupting volcano.

In this chapter we review, for ease of reference and comparative analysis, the evolution of the UK's exclusionary immigration practice dating back to the immediate post-colonial era highlighted by the enactment of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, 1962 and the British Nationality Act, 1981.

The development of British immigration law is firmly rooted in the principle of sovereignty which holds that the state shall act as "essential to self-preservation, to forbid the entrance of foreigners ... or to admit them only in such cases and upon such conditions as it may see fit to prescribe."22 It is the conflict perpetuated by a policy which also defines some UK nationals with certain characteristics as foreigners and who are thus treated as aliens, which makes this discussion relevant. In so far as UK nationality and immigration legislation and policy are interwoven, concluding paragraphs will seek to substantiate the practice of the exclusion of its black nationals with the case of Montserrat as being clear and unequivocal in this regard. In the case of Montserrat and the wider Caribbean, the practice continued to be aided and informed primarily by public fears of the alien intrusion23 notwithstanding a long history of reliance by the UK on the Caribbean to meet its labour demands.24

Following the attempted expulsion of Africans in 1596 "there was never much of an organised immigration policy in the UK and periods of openness were followed by eras of xenophobic obsession."25 Before the 1905 Aliens Act, which was consequent to the Report of the Royal Commission on Alien Immigration in 1903, the principle of 'ius soli'26 was important because a Montserratian by reason of birth within the British empire would have enjoyed not only freedom of movement to the UK but also what we now call the 'right of abode in the UK'.27 The Aliens Act of 1905 was part one in the statutory creation of the alien as an expanding category of people. Bearing on the usual socio-economic and public policy concerns of health, maintenance and accommodation, the Act defined the alien by certain characteristics. The Act affirmed the supremacy of executive authority for the control of aliens and enforced the exclusion of "criminals, prostitutes, idiots, lunatics, persons of notoriously bad character or likely to become a charge upon public funds."28 A right of appeal, was provided for the alien before an Immigration Board at the port of entry during which time "grounds for refusal and a notice of his right of appeal had to be given to him."29

As it coincided with the advent of World War One (WWI), The Aliens Restriction Act, 1914,30 "essentially gave the Secretary of State a free hand to regulate aliens as he saw fit" but provided for special treatment of "alien friends."31 According to Bevan, it was the Aliens Order, 1920 that established the general framework of British immigration control regulation that we still know today. The author's main concern was that the Act resulted in the conversion of "emergency regulation into general law" with its consolidation and adoption of the provisions of the 1914 Act.32 This would naturally have consequences for the Caribbean when the time was ripe for their alienation. As we shall see, the issue of work vouchers emerged in later years as complimentary to stricter exclusionary policies. These vouchers satisfied certain basic requirements not least of which was the retention of a labour pool and the perpetuation of the 'brain drain' from the Caribbean.33

The granting of the status of citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKCs) by The British Nationality Act, 1948 "was done in a spirit of optimism and with an element of 'visions of grandeur'."34 In retrospect, absent the effort to keep the empire together, the British could have been regarded as quite liberal by allowing the enjoyment of dual nationality by its former colonies.35 A small measure of exclusion by the 'ius sanguinis' provision could have suggested a trend.36 The perception of being flooded by aliens may have generated new fears as many Caribbean nationals took advantage of what was now a statutory provision for their settlement in the mother country. The writing was, however, always on the wall for the curtailment of the freedom of movement hitherto enjoyed by Caribbean nationals. By September 1955 it was clear that steps were to be taken to avoid legislating a colour bar, but administering the "measure of discrimination as was desirable."37

By 1958, there was the appeal, both within and outside the British parliament, to end the open door policy for Commonwealth cit.izens.38 For "apart from the effects on employment, housing and education, the implications of large-scale 'coloured' immigration for the cultural and social fabric of Britain were emphasised, frequently in racist language, which was, of course, not prohibited by law at the time."39 By 1962 the Conservative Party government would bring about a dramatic reversal of the legitimate hopes and aspirations of Commonwealth Caribbean citizens to which in 1998 the Labour government acknowledges was a "sense of injustice."40

The 1962 Act was perhaps an unexpected outcome, but its total exclusionary nature was to remain unshaken despite a volcanic-peril facing British nationals on one of the last remaining 'British-dependencies' in the Caribbean.41

For all intents and purposes the 1962 Act42 made aliens of all Commonwealth cit.izens including colonial CUKCs and provided for the general curtailment of non-white immigration. It abolished the use of subject status as denoting citizenship and provided for increased executive powers, tougher enforcement of the 'ius soli' and 'ius sanguinis'43 rules and erased the right of appeal for denial of entry.44 To acquire the invented 'right of abode' a Commonwealth citizen had to:

The discontinuation of rotation migration was a significant blow to families that had chosen to remain split to allow a 'bread-winner' to live and work in the UK. The denial of the right of abode was worsened with the "supplementing by secret instructions" of any discretion that may have been left to immigration officers and even work permit holders were not guaranteed any right of entry.46 Prakash Shah recalls that the late Jamaican Prime Minister, Norman Manley wrote to the Commonwealth Secretariat while the new legislation was being considered: "This Act will be interpreted throughout the world as a failure to face up to the problem of colour presented to England for the first time in history."47 The 1962 Act was a platform for the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, 1968, which retained the assault on the Commonwealth. The 1968 Act brought about an end to primary immigration and introduced the entry clearance certificates as a requirement for dependants.

The British Immigration Act 197148 intentionally defined and classified citizens fundamentally on the principle of 'right of abode'. Other key aspects of the Act included: the formal treatment together of aliens and Commonwealth citizens; tightened controls on non-white persons from the Commonwealth; enabled and encouraged repatriation. The use of the new patriality and the 'ius sanguinis' rule were robustly instructive along with the new immigration rules.49 The requirement by the immigration rules to show that a grandparent had been born in the UK "obviously favoured white British émigrés."50 The provision for arrest powers without warrant of illegal aliens was among the anti-immigration arsenal used against Caribbean nationals.

The 1971 Act had offered a small concession to Commonwealth nationals. Section 1(5) promised that it "shall not render commonwealth citizens settled in the UK at the coming into force of the Act, and their wives and children any less free to come and go from the UK than if the Act had not been passed."51 This slight of the draftsman hand was soon to be corrected by the coming into force of the British Nationality Act, 1981 and its categorisation of British nationals, which changed nothing for Montserratians.52 For all Caribbean nationals the maintenance and accommodation test and the primary purpose rule" (p.p.r.) in a land they had come to know as the "mother country" were particularly onerous.53 The Immigration (Carriers Liability) Act represented other forces, which were to be enjoined in the regimen for exclusion thus laying the foundation for the trials to face Montserratians in 1995. The walls of 1962 had been properly laid and re-enforced with the British steel of law and administrative practice.

The following administrative measures54 will be discussed as forming part of the UK government response to the situation in Montserrat where its nationals faced a volcanic peril.

The Assisted Regional Voluntary Relocation Scheme (ARVRS) was for:

Residents on the island on 16 August 1997 [over one year after the start of the eruption] and who provide written certification that their savings in and outside Montserrat were less than £10,000 per head were eligible to receive financial support amounting to £2,400 per adult over six months ... plus £600 for each child under 18 years of age.55

In seeking to relate the first measures to continue to exclude Montserratians from the UK, I will do so in the context of several meetings and consultations that formed part of the CARICOM response to the situation in Montserrat. As we shall see, the Montserrat experience was not without precedent. Up to January 1997 Montserratians were continuing to relocate themselves to neighbouring islands as they had been doing since the onset of volcanic activity on 18 July 1995. It was at this juncture that the British governor estimated, during an international media interview, that it was anticipated that just over 3,000 islanders would remain the responsibility of the Government once the exodus was over.56 Most of the evacuees were heading to Antigua where pressure was being put on the social services of that island resulting in a shortage of schools and hospital beds.

In an address to the 18th Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community, the Prime Minister of Antigua-Barbuda, Hon Vere Bird moved to seek a resolution to the situation. He told his colleagues:

For over a year now, Antigua and Barbuda has accommodated a large number of Montserratians on our shores and in our Community. In this their greatest hour of need Antigua and Barbuda will continue to open its doors to Montserratians in the spirit of good Caribbean neighbourliness that has always marked our relationship with the island. The prospects for Montserrat in the months ahead are not easy to envisage but appropriate arrangements must be made primarily by the Government of the United Kingdom whose responsibility Montserrat remains.57

Thus, the process whereby Montserratians were being dispersed across the Caribbean was recognised. The situation was also put into the public domain and unto the international plane by the highest level of authority in the region. The new Chairman of CARICOM, Jamaica's Prime Minister, the Rt. Hon P. J. Patterson raised the matter at the 52nd Session of the United Nations General Assembly. He concluded, in part, that the problem may be beyond the capacit.y of the UK Government and appealed to members of the international community to help alleviate the plight of Montserratians.

The fears of the region that Montserratians could be abandoned everywhere was not unfounded. British International Development Secretary, Clare Short who, earlier when the people cried for help, asked if they would be needing "golden elephants" answered the following questions in parliament on 14 October 1997.

Question 1

Will Montserratians living in other Caribbean islands have access to housing, education, social services and healthcare after the six-month period (a reference to the voluntary relocation scheme, which was a six months holiday package [ARVRS)?

Answer

As far as DfID is aware the facilities which other Caribbean islands have made available to Montserratians who have voluntarily relocated are not time limited. The future availability of these facilities is for the governments of those islands to decide.

Question 2

What responsibility does HMG have for those Montserratians now elsewhere in the Caribbean?

Answer

HMG has the usual responsibility for consular protection for Dependent Territories citizens. In addition Montserratians may qualify for financial assistance under the relocation package (a referral back to the ARVRS).58

The answers by the International Development Secretary clearly projected a settled position to disperse Montserratians across the Caribbean through the use of a voluntary holiday scheme that was announced as intended to last six months. At this juncture even the scientists at the MVO could not say that the volcano would return to rest within six months. Further, it would have been unrealistic to return the thousands of Montserratians who had evacuated to neighbouring islands to their homes within six months and in any event there was no organised plan for their departure or return.59 The idea obviously did not sit well with the people of the region. The case of the Kenyan-Asians being shuttled around Europe and elsewhere until the international community had relieved the UK of its full responsibility for its nationals is recalled here as evidence of this recurring situation.60

A Joint CARICOM/OECS Mission to Montserrat on 26 April 1996 led by the Prime Minister of Grenada, Dr the Hon Keith Mitchell re-iterated the "easing of immigration and work permit requirements for migrating Montserratians" relocating to CARICOM member states. By the close of 1997, there was "the proviso that any additional cost should be met by HMG."61

It was only a matter of time before the middle ground administrative efforts to continue to exclude Montserratian was to give way to an acceptance by the UK government of its responsibility under international law to accept them as was upheld in Thakrar v Secretary of State for Home Department. The precedence of that case placed an obligation on the part of the British to accept its own nationals who "had nowhere else to go."62 At least the new Labour government acted before the situation had reached the point of a threatened expulsion from CARICOM countries thus avoiding another possible breach of the European Convention on Human Rights.63 Further efforts at keeping Montserratians outside the 'mother country' were to follow the deceptive six months holiday scheme.

The United States of America granted Temporary Protected Status to Montserratians in August 1997 while Canada granted landed settlement rights. According to the US Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalisation Service temporary protected status was granted to:

An eligible national of a foreign state (or parts thereof) that has been designated for Temporary Protected Status by the Attorney General pursuant to Section 244a of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

By this provision, Montserratians were issued visas for travel to the USA where they were eligible for employment and qualified for social service benefits. They were however required to submit application on an annual basis for a review of their status, or for a change in status. Temporarily protected persons are normally returned to their place of usual domicile. Presumably the United States government had consulted with the HMG before taking this humanitarian act. Comparatively, on 23 April 1996, HMG offered a voluntary evacuation scheme under which "Montserratians able to travel to the UK at their own expense and with a UK sponsor could relocate to the UK ... for two years."64 Given that the majority of the population are transient workers who had by 1996 been mostly unemployed the offer was clearly seen as discriminatory against the poor or at least it targeted the rich.

At the time the official position was that:

HMG remains committed to maintaining a viable community on Montserrat for as long as it remains safe to remain on island and people chose to stay.65

On 15 August 1997 the volcano was unrelenting, but activities continued to reflect the need to contain the movement of the people to Europe. Further evacuations in the sparse northern portion of the island encouraged the British to establish a reception facility at the military Camp Lightfoot in neighbouring Antigua. The facilities at Camp Lightfoot were upgraded at a cost of m£1.5 to the UK taxpayer but were never used. Over the three-year period up to 1997 some £135 million was spent on the Montserrat crisis, but approximately 500 people remain in shelters of a remaining population of 3,500.66 An offer of paid airfares conditional on the family or person having a sponsor in the UK was the alternative. Entry was also still temporary for a two-year period. There was no resettlement grant. Evacuees were however informed that they qualified for every social service in England. Access to these services was another traumatic experience for the comparative few who took the journey and arrived to be greeted to their chagrin as 'refugees'. The UK records put the figure at 1,500 registered on the scheme, but does not reflect how many actually arrived in the UK.67

On 21 August 1997 the ARVRS was implemented to "assist Montserratians needing help to relocate to other countries in the Caribbean and to the US and Canada." The programme was not available for immigration to the UK.

The ARVRS would have successfully dispersed Montserratians throughout the region was it not partly for the intervention of CARICOM governments and possibly some local agitation. In an apparent effort to provide a balanced report, the all party, but mostly Labour party, members of the International Development Committee (IDC) of the British Parliament concluded, "the Government of Montserrat opposed for some time an assisted passage scheme and a relocation grant to assist Montserratians to leave the island."68 It should however be noted that most schemes were targeted and directing Montserratians away from the UK. Further, it will be recalled that HMG's representative has veto power over decisions of the Executive Council. He also had recourse to Statutory Instruments 1959 No. 2206 Caribbean and North Atlantic Territories, the Leeward Islands (Emergency Powers) Order in Council, 1959 under which the island's constitution may be suspended and the governor assume "untrammelled authority."69

In the same report the IDC recommended, one and a half years after the Government had invited Montserratians to make their way to the UK, that:

A liaison officer be established without delay to help Montserratians as they settle in the UK ... and clear and comprehensive information be distributed to Montserratians there concerning their rights and entitlements if they relocate to the UK.70

By 21 May 1998, the two years leave to remain had begun to expire for those Montserratians who had relocated to the UK. The volcano continued to erupt. The following exchange between Foreign Secretary, Robin Cook and members of the IDC on 5 May 1998 was instructive of the reticence on the matter.

Question

The initial two-year grant of leave to remain in the UK expired for the first evacuees in April of this year. What is their current status?Answer

We are actively engaged with the Home Office in looking at what further extension can be provided and I would say to the Committee that there is no question of anybody being required to leave Britain. Their position will be secured. At the moment there is undoubtedly a difficulty in status ...Question

Their legal status is that they are presumably overstayers?Answer

I would hesitate to confer what is a legal term but I can assure you that nobody is contemplating any action against them and I can give you that assurance.Question

Can I ask whether the people concerned have been notified about the position that they are in?Answer

I doubt if they have had any communication because to be fair to those who would be responsible for making such a communication, we would like to be clear what it is we are offering to them before they receive the communication.Question

There have been ministerial statements to the effect that should they relocate to this country they would be permitted to stay as long as they wished because there would be those who have put their children into school and re-established themselves here. I think they ought to be given an assurance that the ministerial statement will be honoured.Answer

I thought I had given that assurance. ... By the way I am advised that on the technical point they are not over-stayers if they have made an application to remain.71

The exchange reflected an uncertainty about the next step to be taken with these British nationals. The answers suggest that there was perhaps a lingering view that the island nationals should continue to be treated as a type of refugee to be processed, after application, for a future status of their choice from among options to be provided.72 The matter was temporarily resolved with the granting of 'indefinite leave to remain' (ILR) to those Montserratians still in Montserrat, in the Caribbean and the UK."73 A fundamental question, which arose, was given that the BDT authorities have consistently objected to the treatment accorded BDTCs, whether there was a case under international law for the reversal of this status. This author is of the view that the denial of the 'right of abode' is tantamount to "an illegal deprivation of nationality (for example on a racial basis) [and that] resumption of the original cit.izenship ... [was] possible."74 Action on the part of the UK government eventually pre-empted this legal step.

It could be that the executive branch of HMG was inclined to reverse the misfortunes promulgated through The Commonwealth Immigration Act, 1962 in the case of its Dependencies in the Caribbean. In a wide-ranging address to the Dependent Territories Association on 4 February 1998 at the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre, London, Foreign Secretary, Robin Cook said he was:

exploring with his colleagues the possibility of granting British cit.izenship to all the cit.izens of those Dependent Territories who do not already have it. Such a move would give all those citizens the right to live and work in the UK. There are complex issues involved in deciding the best approach.

The Foreign Secretary promised that a White Paper was to be produced on the matter. He also lamented that:

My colleagues and I are deeply aware of the unhappiness in the Territories caused by the loss in 1962 of the right of abode in the United Kingdom and the fact that not all became British citizens in 1983 when the present British Nationality Act came into force.

He described the "feeling" of the territories at the time as a "sense of injustice." It will be recalled however that, although the labour party had not voted for the enactment of the 1962 Act, they never opposed it either. According to Evans, there may have been a tacit agreement by labour to the policy for the continued exclusion of non-white Caribbean nationals.75 For the interim however, the grant of ILR to Montserratians was a welcomed relief for many although there were constraints in respect of intra-European travel and access to investment opportunities in the community. In the Treaty of Rome, the UK excludes participation of its BDTCs by defining its nationals as:

The grant of ILR therefore did not allow Montserratians unimpeded access to the free movement of people, capital and services in the wider EU economic area. This opportunity have the potential of generating the level of migrant remittance that aided the development of the island during the 1960s and could again lay the platform for the future self-repatriation of Montserratians. The agreement between the British and Montserrat governments for a programme of voluntary repatriation that commenced in January 199977 did not augur well for the more integrated relationship envisaged for the future. This author is of the view that the voluntary redundancy scheme set the tone for the deprivation of Montserratian evacuees of their civil and political rights on the island. Here again we revisit the apparent insistence for Montserratians to choose to call the UK home or return to the island.78

British citizenship could also have its disadvantages. The free movement arrangement could displace the culture and unique characteristic of this tiny island community. The Government of Montserrat had during the period of the volcano enacted the Immigration and Passport (Economic Residence) Act, 1997. The Act establishes the legal framework for the issue of permits for economic residence. It reflects a high degree of confidence in a land where nature continues to follow its course, but could in the medium to long term prove beneficial in attracting a narrow class of investors. The island's potential as an integrated member of the EU could far outweigh this avenue for development.

There is also the equally unique fact that Montserrat enjoys full membership status within the Caribbean Community. Its future as a gateway to Europe ought not to be hindered by this fact. The foregoing concerns may also reflect those of the other four British Dependencies in the Caribbean for which the offer of a possible reversal of the 'injustice' brought about by the 1962 Act should for now be considered as a very warm apology. Following this landmark apology however, Foreign Secretary, Robin Cook returned to being quite nebulous with regard to the future of the BDTCs when he answered the following questions before the IDC on 5 May, 1998.

Question

Secretary of State, I feel very uneasy about this financial arrangement. To me it seems like a bit of an insult to the people of the - I thought we were supposed to be calling them - British Overseas Territories now not Dependent Territories. It is rather an insult for them to be dependent on aid. They are part of our nation, they are part of us?"Answer

First of all you are quite right it is our policy to re-designate them Overseas Territories. That will require legislation, and although certainly I will encourage and try myself to use in public discussion the term Overseas Territories, the fact is that the legal term is Dependent Territories and therefore that guides our administrative terms.79

I have attempted in the foregoing paragraphs to document and discuss the political and administrative responses of HMG to a crisis in one of her territories as being principally informed by a policy to exclude them from entry to the UK even at great cost. An abundance of historical and legal evidence supports the assertion that the implementation of administrative and legislative measures has consistently being targeted against these British nationals to keep them out of England. The repeated scientific analysis was for an eruption lasting beyond ten years, yet this was ignored and considerable effort and money was spent to deposit the Montserratians in neighbouring islands. As in the East African case, neighbouring Antigua and Barbuda was granted debt forgiveness and additional aid to refurbish local schools and health centres all in a bid, which would have kept the Montserratians out of the UK. The efforts to disperse Montserratians across the Caribbean failed because the region refused to let history repeat itself and growing pockets of protest on the island brought the subject under critical international spotlight. The establishment of hospitality centres in Antigua-Barbuda and Guadeloupe was compounded by the grant of temporary leave of two years to remain in the UK for evacuees. This decision was clearly not based on the available scientific data.80 The grant of 'indefinite leave to remain' to those who had travelled to the UK as a last respite, only informed the possible future of a limited few (approximately 3,000).

The future of Montserrat was, for a moment, balanced between the sincerity of the executive of HMG and the contents of a White Paper81 that was pre-empted by an agreement to implement a voluntary repatriation programme for Montserratians as of January 1999. The eventual incorporation of Montserratians in a common British citizenship status as of 21 May 2002 does not completely resolve the many relationship issues with the mother country indeed it has further complicated them. Montserratians must still choose between Montserrat and the UK as their rightful place of abode. They will also be subject to a range of residency tests in order to access certain critical health, welfare, education and other public services in the UK. The free movement and other EU rights also remain an untapped economic potential for the island itself. The fact that race can be posited as a justification for the practice of exclusion raises certain fundamental human rights concerns. The history of British exclusionary policy towards the Caribbean since 1962 and the Montserrat experience are therefore at least cause for apprehension and uncertainty if not concern among the people of Montserrat.

Ambeh, William [1996]: 'Volcanic History of the Eastern Caribbean.' Government In Action '96. Special February Volcano Issue, Vol.3 No.2A.

Bevan, Vaughn [1986]: The development of British immigration law. London: Croom Helm.

Blake, Nicholas and Richard Scannell [1988]: 'The Immigration Bill: just the limited reinforcement of the 1971 Act?' Immigration and Nationality Law and Practice. Vol. 3 No. 1 [April 1988], pp. 2-4.

Boehning, W. R. [1972]: 'No entry to Europe for non-patrials.' Race Today, July.

Bottomley, A. and G. Sinclair [1970]: Control of Commonwealth immigration. London: Runnymede Trust.

Brownlie, Ian [1990]: Principles of Public International Law (4th ed.), Oxford University Press.

Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Secretariat. Report of the 18th Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community, Montego Bay, Jamaica, 4 July, 1997.

Caribbean Community (CARICOM) [1991]: Time for Action: The Report of the West Indian Commission, Georgetown, Guyana.

Commission for Racial Equality [1985]: Immigration control procedures: Report of a formal investigation. London: C.R.E.

Cook, Robin, Secretary of State for Foreign [1998]: Speech to the Dependent Territories Association, Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre, London, 4 February 1998. Published at www.fco.gov.uk (see copy appended as Annex II).

Davison, R.B. [1962]: West Indian migrants: social and economic facts of migration from the West Indies. Oxford University Press.

Deakin, N. [1968]: 'The politics of the Commonwealth Immigrants Bill'. 39 Political Quarterly, No. 1.

Dummett, Ann and Andrew [1990]: Subjects, citizens and others. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

Evans, J.M. [1983]: Immigration law. 2nd ed. London: Sweet and Maxwell.

Fransman, Laurie [1989]: Fransman's British nationality law. 2nd ed. London:Fourmat Publishing.

Green, Penny [1989]: Private sector involvement in the Immigration Detention Centres. London: Howard League.

House of Commons, International Development Committee[1997]: First Report, Montserrat: Report, together with the Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence and Appendices, The House of Commons, 18 Nov. 1997.

International Development Committee [1998]: Sixth Report: Montserrat - Further Developments: Report and Proceedings of the Committee together with minutes of Evidence and Appendices, The House of Commons, London, 28 July, 1998.

Jackson, David [1996]: Immigration: Law and practice. London: Sweet & Maxwell.

Joint Council for the Welfare of immigrants [1990]: Target Caribbean: The rise in visitor refusals from the Caribbean. London. Reviewed by Jim Gillespie in INLP, (January 1990) Vol. 4 No.1 pp. 4.

Jones, K. and A. D. Smith [1970]: The economic impact of Commonwealth immigration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Macdonald, Ian A. and N. Blake [1987]: Macdonald's immigration law and practice. 2nd ed. London: Butterworths.

Macdonald, Ian A. and N. Blake [1991]: Macdonald's immigration law and practice. 3rd ed. London: Butterworths.

Macdonald, Ian A. and N. Blake [1995]: Macdonald's immigration law and practice in the United Kingdom. 4th ed. London: Butterworths.

Peach, G. C. K. [1968]: West Indian migration to Britain: A social geography. I.R.R./ Oxford University Press.

s. 1989 No. 2401 Caribbean and North Atlantic territories: The Montserrat Constitution Order 1989, edited by Albert P Blaustein, September, 1993.

Shah, Prakash [1995]: "Coping with 1997: The Reaction of the Hong Kong People to the Transfer of Power." 8-9 British Nationality and Immigration Laws, pp 57.

Steel, David [1969]: No entry: The background and implications of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968. London: Hurst & Co.

Tilbe, D. [1972]: The Ugandan Asian Crisis. British Council of Churches.

White, R. C. [1965]: Administration of public welfare. 2nd ed.

www.caricom.org

www.cdera.org

www.montserratreporter.com

www.fco.gov.uk

Fig. 1: Map of Montserrat (click on map to see larger version)

Chronology of main activities/events on volcano-troubled Montserrat 1995-2002

18 July, 1995

Resumption of volcanic activity after over 350 years of dormancy

28 July

Village of Long Ground relocated to nearby [Bethel] village considered safe

7-15 August

East, South and Southwest villages relocated to central and northern areas

21 August

Major ash fall covers capital. Scores of Montserratians evacuate themselves to neighbouring Antigua

7 September

Eastern Villages remain evacuated, but all others re-occupied including the capital Plymouth

October

Plymouth re-evacuated as dome growth and major ash falls generate fear

November

Villages of the eastern corridor evacuated

December

All eastern and southern villages evacuated following major pyroclastic flows in the east

January 1996

3 April

Increased pyroclastic flows in the east. Third evacuation of Plymouth although only expected to last one month it remains in force.

23 April

HMG announces grant of leave for Montserratians to relocate to the UK at their own expense and provided they had a UK sponsor.

26 April

CARICOM reiterates bilateral arrangements for the unconditional relaxing of immigration and work permit requirements for Montserratians where they existed. Montserratians were already work permit free in Antigua-Barbuda and St Kitts-Nevis.

4 July

CARICOM announces unconditional offer of hospitality arrangements for Montserratians fleeing the volcano. 17 September 1996

First explosive event of the volcano. Widespread destruction in Long Ground village. Communities South of Belham Valley advised to evacuate

4-8 August

Explosions occur at roughly 12hr intervals. Scientists declare the island relatively safe.

15 August

Revised scientific volcanic threat suggests risks extending to areas further north (Salem).

25 June 1997

Major pyroclastic flows result in 19 dead and others were missing.

15 August, 1997

HMG offers free passage and reception services in Antigua. Salem and environs declared unsafe for nighttime occupation. Critical shortage of shelter and housing in the north persist

4 July

CARICOM announces that cost of further evacuee assistance must be met by HMG.

15 August

HMG offers airfares to the UK for those with sponsor only.

21 August

HMG announces Assisted Regional Voluntary Relocation Scheme (ARVRS) for six-month period of stay.

05 September

HMG announces that self-relocated evacuees qualify for ARVRS.

22 September

Sustained explosive activity abates by year-end

21 May 2002

Restitution of British citizenship to Montserratians & other DTs

1

2

4

6

11

12

14

18

21

24

28

29

30

35

36

42

43

45

46

47

48

51

54

58

60

62 63

64

66

67

68

70

71

72

77

78

79

80

81 © Claude Hogan, 2003.

HTML last revised 14 February, 2003.

HTML last revised 14 February, 2003.

Return to Conference Papers.