Galways Boilinghouse

Click on the picture to see a larger version

Excavations at Galways

Click on the picture to see a larger version

My interest in tourism in Montserrat started in the early 1980s when I began a long-term historic site study at Galways Estate in the St. Patrick's region in far southern Montserrat. Between 1980 and 1995, I brought more than 150 volunteers and students to work on archaeology research at Galways and soon learned that the visitors needed help in understanding Montserrat, but also, Montserratians needed help in understanding their visitors. [We might call those who came to work at Galways people a cross of "adventure" and "academic" tourists.] I also frequently dealt with cruise or "day trip" tourists visiting the Galways site and in time taxi drivers asked me to help them develop tours for their clients through the Galways ruins and digs. As I began designing brochures for tourists on the Galways research, I thought more and more about how we might engage the intellectual curiosity of those who came to visit our site.

Galways Boilinghouse

Click on the picture to see a larger version

Excavations at Galways

Click on the picture to see a larger version

When the Galways research was chosen to feature in the Seeds of Change exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (1991-1993), Lindblad Expeditions, a tour company based in New York, asked me to design 10-day Caribbean educational cruises for 65 passengers aboard the Sea Cloud, a four-masted sailing vessel. I served as the lecturer on seven of those cruises. That experience taught me that tourists could become deeply engaged with the places they visited and that certain kinds of tourists yearned for travel experiences that gave them something critical to think about. Eventually, after observing tourism development in Southeast Asia, South Asia, Turkey, Central Europe, and Western Europe, as well as the Southeastern United States, I wrote a short critique of the Caribbean tourism experience.1 I began to encourage my graduate students to do research on Caribbean tourism, and I started to include coverage on tourism as a development strategy in most of the courses I taught and eventually in the textbook I wrote.2 These tourism related experiences and other observations led me to some understanding of what tourism can and cannot do for Caribbean places. As a geographer, I have been thinking about how one might re-envision the entire tourism phenomenon so that on many levels it is more rewarding for both the hosts and guests. My following comments apply specifically to Montserrat, but could be generalized to other destinations.

First, it seems essential that the most important question tourism planners need to address is the “Development for whom?” question, meaning tourism should be a strategy in Montserrat only if it will truly serve the goal of improving life for the local population. What constitutes “improvement” can only be defined by an informed local dialogue. Second, Montserrat’s tourism product might best build on its present niche in the tourism market (residential tourism) and develop additional locally designed and implemented tourism products that are informed by this successful experience. Third, it seems wise to create a tourism experience that engages the intellect of both visitors and hosts and encourages in them humanitarian responses to each other. In so doing, this experience should make optimal use of Montserrat’s social and natural capital, and (importantly) the social and natural capital of the tourists, in order to achieve comprehensive social and physical sustainability. In other words, the tourism experience should be intellectually rewarding for all concerned, financially rewarding for Montserratians, and tourism should be designed to capture the maximum of tourist expenditures for the local economy.

Throughout colonial history, despite considerable outside intervention in its economy, Caribbean people have relied on their own initiative and local resources to construct a local way of life supported by a multitude of activities. In Montserrat, even before the end of slavery, when plantation crops were the supposed basis of the island economy, in reality everyday livelihoods were grounded in the household and community. Each household supported itself through cash and subsistence gardening, small wage labor, animal tending, petty capitalism, sewing, carpentry, and remittances from migrant family members. All of these multiple livelihood strategies were for the most part under the control of Montserratians and though emphasis would shift as local and global circumstances changed, local control and initiative was a lynchpin of survival.

I suggest that this livelihood model is a wise one for the modern world and should be imitated in current development planning. If tourism is to be an important part of Montserrat’s future, it must be locally guided and it must have multiple aspects that insure flexibility. Flexibility must be a feature geared to respond not only to the exigencies of an unpredictable volcano, but also to constant shifts in the global economy.

First, I propose that Montserrat join a small group of forward-thinking global tourism sites that in 1999 founded the International Coalition of Historic Sites of Conscience (ICHSC). These now thirteen “Sites of Conscience”6 were founded by the following:

The founding members of the ICHSC, believe that such sites should assist the public in drawing connections between the history embodied in the site and the modern world of which they are a part. The primary mission of such sites is to promote humanitarian and democratic values, so that visitors are inspired to genuinely embrace diversity and to become actively involved in contemporary community issues in their own home places. In other words, I am suggesting that Montserrat take a bold step away from the Sun, Sea, and Sand model of Caribbean tourism and forge a new image for itself based on a more self-confident and intellectual approach to attracting, primarily, visitors of conscience.

Montserrat’s qualifications for being a Site of Conscience begin with its historic role in the colonial plantation/slave economy and flow to its present predicament as a victim of closely spaced devastating natural disasters. But Montserrat’s qualifications are also linked to its pioneering efforts since WWII to find sustainable and humane ways to support its people despite its tiny size, remote location, fragile environments, limited tropical island resources, and relative powerlessness in the face of global economic forces.

At this point in time, Montserrat must deal with problems of providing an adequate modern standard of living without compromising local social values, yet within a global economy. It must also deal with special environmental, social and economic circumstances that are the consequences of two major natural hazards: hurricanes which threaten every year (Hurricane Hugo struck in 1989) and the continuing volcanic crisis which commenced in July 1995. Due to these two hazards, Montserrat must meet the challenges of dealing with drastically reduced population and living space, financial loss, and the personal loss of sense of place and purpose.

Montserrat former settlement map

Click on image to see a larger version

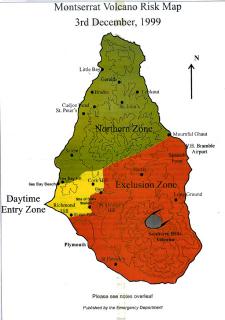

Exclusion zone

Click on image to see a larger version

My proposal is that in addition to reviving residential tourism to the extent possible under present circumstances,7 Montserratians create and market to a wide range of clients new knowledge-based locally-designed tourism products that make the best possible use of the island’s rich social and natural capital. I choose the term knowledge-based to stress the point that this will be a clear departure from the Caribbean tourism that has too often replicated the dynamics of colonial era in constructing the relationships between guests and hosts. Infusing the knowledge-based touristic experience from beginning to end would be the idea that Montserratians are in charge of their own place and have much wisdom and rich experience to exchange with visitors, who themselves are often seeking humane ways of dealing with the modern world. The tourism products would be locally designed and implemented, with the advice of only those consultants that Montserratians themselves choose from a range of competitive bidders who share this philosophy. The products would make optimal use of Montserrat’s social and natural capital for all-round social and physical sustainability. The jobs created would be rewarding for Montserratians — intellectually, financially, and spiritually — and the system would capture the maximum tourist expenditures for the local economy.

I. Distance Learning: Before coming to the island, clients would proceed, via the Internet, through a well designed program of study on Montserrat’s geography, defined broadly. They would be introduced to Montserrat’s Caribbean context: its physical environment – the tectonic past and future, its flora, fauna, terrestrial and marine features, its fragile island biogeography, and human ecology. They would also learn about its pre-history, the plantation slavery economy of the colonial period, and how this system segued into the mass migration of the 1950s and then, during the late 20th century into a broadly based (multi-strategy) economy based on several kinds of tourism (residential, extended stay hotel visits, day trips, archaeological field work, small conference hosting), light manufacturing, off-shore medical education, off-shore banking, and remittances and reinvestment from Montserratians abroad.

For many, the experience of Montserrat might remain at this level of “distant engagement,” perhaps with the Internet purchase of some books, videos, music CDs, and condiments produced on and marketed by the island. Earnings are estimated at $50.00 per client for an estimated 10,000 clients per year = US$500,000.

Montserrat products

Click on image to see a larger version

II. Remote Observation and Public Education: For some who become engaged by Component I (or simply hear about the island), the experience of Montserrat might intensify to “remote observation,” involving a cruise through nearby waters and the chance to view the coastline, the volcano in whatever state of activity it may be in, and the Pompeii-like capital of Plymouth and surrounding villages and landscapes. Income to Montserrat from such cruises would come in the form of head-taxes charged to any vessel that came within a three-mile limit of the shore.8 As of January 2000, passenger cruise ships were stopping off Montserrat at the rate of four to six a week, for exactly this purpose, but at no charge. A typical such ship carries 2,000 passengers. A charge of even US$2 per head for four ships would add annually US$800,000 to the island income. If a volcano public education specialist from the MVO could be placed on board via helicopter or launch to lecture to the passengers, a higher fee could be charged. US$3/per capita would bring in a potential US$24,000 per week or US$1.2 mil+ per year. Yet the cost to Montserrat and the environmental impact would be nil. Lectures on Montserrat’s social history could also be so provided on board the ships.9

III. Planned Knowledge-based 3-5 day package trips: For a select group of people who have gotten to know the island over the Internet or through an offshore cruise visit, an actual trip to Montserrat might ensue. Travelers could choose from a variety of products, all of which would entail further study with Montserratian experts on particular subjects. The study packages would be planned to leave the maximum income in Montserrat with the least environmental impact, to create interesting and rewarding jobs for Montserratians, and to attract repeat visits. Estimate 5,000 tourists a year,10 spending US$300 per day, staying for an average of 5 days = US$7.5 mil./yr.

| Actual visitor and Tourism data | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 |

| Visitor and returning resident arrivals | 41,731 | 27,564 | 20,826 (estimated) |

| Tourism earnings (estimated) | US$ 21.6 mil | US$ 8.4 mil | Data not yet available |

Volcanic event in Plymouth

Click on image to see a larger version

Tree ferns in the rain forest

Click on image to see a larger version

Woman in rain forest

Click on image to see a larger version

Pre-volcano house in the far south

Click on image to see a larger version

Pre-volcano houses in Kinsale

Click on image to see a larger version

Post-volcano replacement house

Click on image to see a alrger version

Children's steel band at Galways

Click on image to see a larger version

Montserrat has a more than 20-year history of community engagement with historic site research and preservation. The Galways Estate project engaged the attention and labor of the St. Patricks community and of many others throughout the island from 1980 to 1995, when the volcano became active11 and the experience continues to knit together the dispersed members of this research community. Montserratians and their expatriate visitors also have cooperated on other historic projects including sites at Bramsby’s Point, St. George Hill, Carr’s Bay and elsewhere. Nearly all these sites have been lost due to vulcanism, but the important historic site at Little Bay remains to be thoroughly studied and interpreted. Dating from the mid-17th century (it is shown on the unusual coastal profile 1673 map of Montserrat),12 this is undoubtedly one of the very oldest historic sites (as opposed to pre-historic) on the island. It offers the chance to provide to the Caribbean tourism market something that is nearly entirely lacking in the region: a well-studied and imaginatively interpreted site from the colonial era. A proposal to study and interpret the Little Bay site for local and visitor benefit has recently been submitted to the Montserrat Government.13 This proposal makes the case for heavy local involvement in the planning and execution of the research and interpretive project and would emphasize the human values and perspectives of other Sites of Conscience.

IV. Revival of Residential tourism: At least 200 of Montserrat’s stock of villas remain useable. If these houses were each occupied just two months out of the year by by just two people who spend US$300 per capita per day (for food, utilities, service, transport, entertainment, and rent or home maintenance) for these 60 days, this sector of tourism would bring in US$7.2 mil.14

Typical Montserratian villa

Click on image to see a larger version

Essential perquisites for this component are the replacement of the airport, golf course, and club house destroyed by the volcano. Air travel is favored by those likely to inhabit the villas and golf is an activity highly valued by them for exercise and social activities. Estimated cost of replacing these facilities is: Airport: US$16 million and 9-hole Golf course/clubhouse: US$1 million if the present facility is rebuilt, as much as US$80 million if an entirely new golf facility complete with villas and other amenities is built in a new location.

The world is changing. The standard Caribbean tourism product, which was never very good at putting Caribbean people in touch with their visitors, is losing popularity while cruise tourism, a product that leaves remarkably little income in host islands and fosters only the most superficial of human interaction, is gaining in popularity. Yet, paradoxically, studies show a growth in the number of people who seek personally rewarding and philosophically uplifting cross-cultural travel experiences. The Caribbean is well positioned to provide such experiences if an entirely new stance vis à vis visitors can be adopted by Caribbean people. The stance would be markedly more self-confident and proactive aimed at giving (selling) visitors a chance to learn useful information and humanistic perspectives while sojourning in Montserrat. Island people have for years informally provided such experiences to expatriates and academics — the testimonials to the uplifting experience that a sojourn in Montserrat can be are legion — but a larger market awaits.

Potential annual income for Montserrat as a Site of Conscience

| I. Internet and external public education component | 500,000 |

| II. Cruise observation and education component | 1,200,000 |

| III. Planned Knowledge-based 5-day package trips | 7,500,000 |

| IV. Residential tourism component | 7,200,000 |

| Total | US$ 16,400,000 |

3

4

6

© Lydia Pulsipher, 2003.

HTML last revised 20 April, 2003.

HTML last revised 20 April, 2003.

Return to Conference Papers.