Caries

prevalence and experience of 12-year-old children in Montserrat

Coretta E.

Fergus

Introduction

The primary aim of this study

was to conduct an epidemiological survey of all 12 year olds on

Montserrat in order to:

- Determine the caries

experience

measured by the DMFT index and Oral Health Related Quality of Life

(OHRQoL) of 12 year olds

- To explore the differences

in

caries experience by gender, and socioeconomic status

No previous data could be found

on the oral health status of Montserratian people and the oral data

bank compiled by World Health Organisation (WHO) is devoid of any oral

health data for the island. With inadequate previous data this

investigation may be timely as it will provide some baseline data for

measurement of effectiveness of interventions to reduce caries in 12

year olds and could influence policy makers in the development of new

oral health policies.

Methods

Preliminary planning

Permission for conducting the

survey was sought and granted by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in

Montserrat and also from the principal of the Montserrat Secondary

School. Consent letters were distributed to the relevant children on

behalf of the researcher.

Training and calibration

Separate training and

calibration were carried out in line with BASCD guidelines for the

conduct of surveys of child dental health [1] and [2]. [These numbers

refer to the numbered list of references.] The calibration

was conducted at the Lister Primary Care Centre in Peckham where

inter-examiner reliability between the Author and the benchmark BASCD

examiner was measured.

For the fieldwork the recorder

was trained in recording data by the Author who conducted all

examinations. An assistant was responsible for co-ordinating the

children.

Subjects Study Population

All 12 yr olds in Montserrat

were invited to be part of the survey which was carried out on 14th

March 2006. In total there were 46 pupils who all attended the only

secondary school on the island. Positive consent was sought 2 days

prior to examination and 32 students responded positively. The

remaining students failed to return consent forms from parents and were

therefore not permitted by the school authority to take part. This was

in

accordance with exclusion criteria of the study.

Equipment

- CPITN probe Disposable

non-latex gloves

- Sterile cotton gauze Data

recording sheets

- Mouth mirror, Plane No.4 Desk

- Dental face shield

Standardized

light source

Examination procedure

Children presented to

examination room in no particular order. They were first asked to

complete the “Child Oral Health Questionnaire”. The

assistant recorded name, date and parental occupation on data forms.

Each child was given a data form and directed to the examination. Data

forms were handed to recorder who then went on to record data as

instructed by examiner.

Each child was asked to lie on

the desk in a supine position with examiner positioned directly behind.

A Tikka Petzl (3LED) head lamp was used for a light source. Examination

packs consisting of a sterile CPITN probe and sterile gauze and

disposable mirrors were unwrapped by dentist for each child.

Tooth surfaces were dried with

sterile cotton gauze and examined in a standard order as specified by

the study protocol. Following the examination all instruments were

placed in a “dirties” container and gloves disposed

of in a clinical waste bag. No radiographs were taken.

Any child requiring treatment

was identified and parent informed and advised by letter to seek

appointment at the local dental clinic.

Cross infection control

A standard cross infection

prevention protocol was followed. The examiner wore a face shield

through out the examination and gloves were changed after each patient.

Intra-examiner reliability

Five subjects were re-examined

and statistical test applied to determine intra-examiner reliability.

Data analysis

Data were processed using

Dental Survey Plus 2 version 2.1 and Statistical Package for Social

Sciences (SPSS version 14) software for the purpose of obtaining

descriptive statistics.

Results

Calibration of examiners

High levels of agreement were

recorded (Kappa = 0.81) between the BASCD ‘gold

standard’/benchmark examiner and the Author (Fergus CE). Five

child subjects were examined and scored using the DMFT Index and the

BASCD caries criteria.

Characteristics of the sample

Of the 46 twelve-year-olds in

Montserrat 32 participated in the survey. This gave a response rate of

69%. A description of the participants by gender and parental

occupation is given in Table 1. There were slightly more boys than

girls.

Table 1. Distribution

of

12-year-old participants by gender and father’s occupation

|

|

No. of children |

% |

| Gender |

Male |

18 |

56 |

|

|

|

|

|

Female |

14 |

44 |

|

|

|

|

| Father's occupation |

Legislators |

1 |

3 |

|

Professionals |

7 |

22 |

|

Technicians |

3 |

9 |

|

Clerks |

2 |

6 |

|

Service workers |

5 |

16 |

|

Skilled agricultural |

2 |

6 |

|

Craft & Trade |

6 |

19 |

|

Plant & Machine |

3 |

9 |

|

Elementary occupations |

0 |

0 |

|

Armed Forces |

0 |

0 |

|

Not given |

3 |

9 |

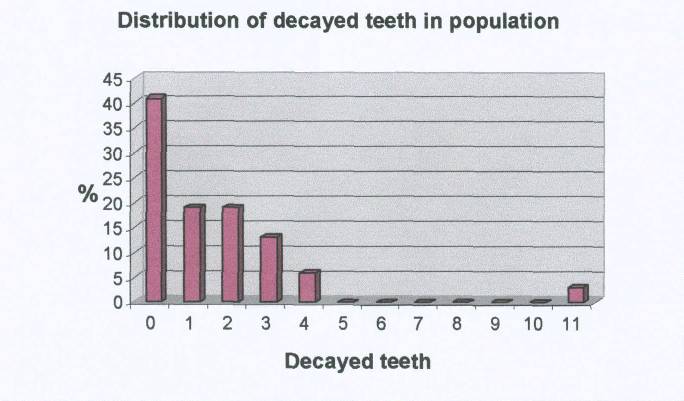

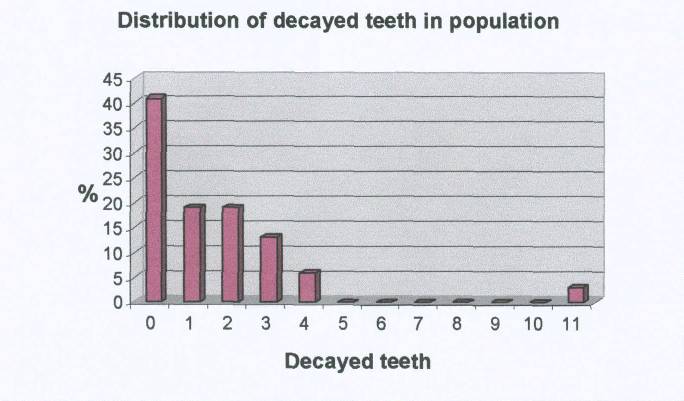

Caries experience

The sample of 12 year olds had

a mean DMFT of 1.91 (C.I. 1.05 to 2.76), (Table 2). Fifty-nine percent

had experience of decay in one or more teeth (DMF>0) (See Figure

1). Conversely only 41% of the children were caries free. One child

recorded with a DMFT of 11 (Table 3). All children with caries

experience were seen to have active, untreated caries (D>0) and

therefore normative treatment need. Few restorations were recorded

deriving a Care Index of 16%. Very few extractions had taken place. The

participants had an average of 25.69 (C.I. 24.8 to 26.58) sound teeth.

Table 2. Caries

experience of

12-year-olds in Montserrat

|

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Confidence Interval |

| D |

1.53 |

2.16 |

0.75-2.31 |

| M |

0.06 |

0.25 |

-0.03-0.15 |

| F |

0.31 |

0.64 |

0.08-0.54 |

| DMFT |

1.91 |

2.37 |

1.05-2.76 |

|

|

|

|

| Care

Index % |

16 |

|

|

Figure 1:

Relative Distribution

of decayed teeth in 12-yr-old population

Table 3. Relative

Distribution of DMFT scores in 12-year-old population

| DMFT |

Number |

% |

Cum |

Cum % |

| 0 |

13 |

40.63 |

0 |

40.63 |

| 1 |

3 |

9.38 |

13 |

59.38 |

| 2 |

6 |

18.75 |

19 |

78.13 |

| 3 |

3 |

9.38 |

25 |

90.63 |

| 4 |

5 |

15.63 |

29 |

96.88 |

| 5 |

0 |

0.00 |

31 |

96.88 |

| 6 |

1 |

3.13 |

31 |

96.88 |

| 7 |

0 |

0.00 |

31 |

96.88 |

| 8 |

0 |

0.00 |

31 |

96.88 |

| 9 |

0 |

0.00 |

31 |

96.88 |

| 10 |

0 |

0.00 |

31 |

96.88 |

| 11 |

1 |

3.13 |

32 |

100.00 |

Caries experience and

socio-demographic characteristics

Tables 4 and 5 show the

breakdown of caries experience according to gender of the child, (Table

4) and the occupation of the father, (Table 5). In both cases numbers

of children in the survey are too small for significance testing.

However, there does not appear to be any difference in overall caries

experience between males and females, but there is a trend towards

greater caries experience in non-professional groups. Three children

did not give a paternal occupation (Table 1).

Table 4. Caries

experience of 12 year olds by gender in Montserrat [Mean (S.D.)]

| Gender |

D |

M |

F |

DMFT |

Confidence Interval |

Sound Teeth |

| M |

1.39 (2.64) |

0.06 (0.24) |

0.28 (0.67) |

1.72 (2.93) |

0.27-3.18 |

25.56 (3.07) |

| F |

1.71 (1.38) |

0.07 (0.27) |

0.36 (0.63) |

2.14 (1.46) |

1.30-2.99 |

25.86 (1.46) |

| Overall mean |

|

|

|

|

|

25.69 (2.47) |

Table 5. Caries

experience of 12 year olds by father’s occupation in

Montserrat [Mean (S.D.)]

| Parent occupation |

D |

M |

F |

DMFT |

Sound Teeth |

|

Legislators |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

27 |

| Professionals

|

1.29 |

0.14 |

0.29 |

1.71 (2.43) |

25.57 |

| Technicians |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 (1) |

24.33 |

| Clerks |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 (2.83) |

26 |

| Service workers |

0.6 |

0 |

0.4 |

1 (1.41) |

27 |

| Skilled agricultural |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 (1.41) |

25 |

| Craft & Trade |

3 |

0.17 |

0.17 |

3.33 (3.93) |

24.67 |

| Plant & Machine |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

28 |

| Elementary occupations |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Armed Forces |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Not given |

2.33 |

0 |

1 |

3.33 (1.15) |

24.67 |

Quality of life data

Table 7 shows the distribution

of some responses to individual items on the Child Perceptions

Questionnaire for the 32 children surveyed. Most children (78%) rated

their oral health as “good” or better. The worst

commonly reported items were breathing through the mouth, slow eating,

food sticking between teeth, feeling upset or nervous about appearance

of teeth, difficulty doing homework because of problems with the mouth

or teeth and difficulty drinking or eating foods. A lower score

represents a lesser impact on QoL than a higher score.

Table 6. Descriptive

statistics

for the CPQ

| Jokovic

A; Locker D; Stephens M; Kenny D; Tompson B; Guyatt G (2002)

Validity and reliability of a questionnaire for measuring child

oral-health-related quality of life,

Journal of dental research

81(7): 459-63. |

|

Males

(19) |

Females

(13) |

Total |

Jokovic

et al. 2002 |

| QoL

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Mean

|

SD |

| Oral Symptoms

|

3.00

|

3.27

|

3.15

|

2.44

|

3.06

|

2.92

|

6.3

|

3.4

|

| Functional Limitations

|

7.61

|

6.04

|

9.82

|

6.98

|

8.45

|

6.39

|

6.7

|

4.9

|

| Emotional Well Being

|

6.89

|

4.97

|

6.23

|

5.23

|

6.63

|

5.00

|

6.4

|

5.7

|

| Social Well Being

|

7.00

|

6.10

|

5.92

|

7.38

|

6.56

|

6.55

|

6.9

|

6.4

|

| Total

|

24.28

|

18.01

|

23.44

|

22.15

|

24.00

|

19.06

|

26.3

|

16.7

|

Table 7. Results of the

CPQ: Scores for some items of health impact on QoL

| Item |

Excellent |

Very Good |

Good |

Fair |

Poor |

|

N (%) |

| Oral Health |

7 (21%) |

7 (21%) |

12 (36%) |

5 (15%) |

2 (6%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all |

Very Little |

Some |

A lot |

Very much |

|

N (%) |

| Life overall |

18 (55%) |

10 (30%) |

2 (6%) |

1 (3%) |

2 (6%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Never |

Once/twice |

Sometimes |

Often |

Everyday/Almost every day |

|

N (%) |

| Upset |

11 (33) |

7 (21) |

8 (24) |

7 (21) |

| Food stuck between teeth |

5 (15%) |

11 (33%) |

11 (33%) |

3 (9%) |

3 (9%) |

| Difficulty doing homework |

18 (55) |

6 (18) |

3 (9) |

5 (15) |

1 (3) |

| Breathing through mouth |

9 (27) |

10 (30%) |

4 (12%) |

6 (18%) |

3 (9%) |

| Slow eating |

14 (42) |

5 (15%) |

8 (24%) |

1 (3%) |

5 (15%) |

Measurement of examiner

reliability

A randomly selected 5 of

the 32

subjects were re-examined at the completion of the main survey. Kappa

was used to determine intra-examiner reliability. The result of the

Kappa test was a score of 1, perfect agreement

Discussion

Caries Experience

The results of the study

indicate that the sample of 12 year olds examined have a mean DMFT of

1.91. This indicates that Montserrat has achieved the oral health goal

set by WHO of reaching a mean DMFT score of ≤3 by 2000

(Fédération Dentaire Internationale, 1981; WHO,

1988).

The mean number of Decayed

teeth being 1.53 (CI 0.75 to 2.31) contributes the highest proportion

of the total figure (D=1.53, M=0.06, F=0.31). The sample of 12-year-old

children had on average in excess of one an a half teeth with an

untreated cavity. The majority of children examined (59% with

D>0) were experiencing some form of active decay thus requiring

(professionally judged) treatment. Active caries (D component) was

measured at an advanced stage of the carious process when there was

clear visual dentinal involvement. This does not relate to treatment

need directly. There is recognised large underscoring in converting the

‘D’ component, in epidemiological studies, to

actual treatment need [3]. The indication is that there were quite high

levels of untreated decay amongst this population of children examined

and consequently high normative needs. This may imply that current

services are failing to meet this need.

The filled component of the

DMFT score was also fairly small at, 0.31 (0.64) and this was also

reflected by a low Care Index of 16%. The Care Index measures the

number of filled teeth in relation to dental disease and can therefore

gives an idea of the level of restorative care or treatment services

being provided. The Care Index is comparatively low when set against

the same age group in the UK. The 2000/01 BASCD study of 12 year olds

in England reported a Care Index was 48%. It can be argued that it is

inappropriate to compare a developing island state with a developed

country but this comparison gives an indication of the standard that

Montserrat should aim at. The other reality is that there is a lack of

regional data which goes beyond quoting DMFT to actually examining the

amount of care and describing treatment needs and amount of care being

delivered. Based on the information collected, that there was high

active caries and little restorative care in the children examined, it

is reasonable to presume that the free government service in Montserrat

may be being underutilized.

The mean number of Missing

(extracted due to caries) teeth was the lowest component, being less

than 1. This may reflect the following: 1) children are retaining their

teeth 2) children are not having extractions as a treatment for dental

decay which may be because much of the decay could be restored. 3)

children are not accessing dental care and receiving treatment.

Gender Distribution

It is difficult to

determine

from this small sample size whether the higher DMFT scores observed in

females was statistically significant. Nonetheless in the studies that

observe a higher caries experience among girls they tend to attribute

it to females having a greater propensity for sweet foods or poorer

dietary habits [4]. The explanation put forward by the author is only

speculative and may not be scientifically supported. No significant

differences in the dentinal caries experience of boys and girls were

reported in the Child Dental Health Surveys, UK, 2003 [5]. However

girls were more likely to brush twice a day than boys [6]. Such

findings have implications for how dental health interventions are

delivered.

Socioeconomic Status

The father’s

occupation was used as an indirect measure of child socioeconomic

status. Montserrat does not have distinct social class system so this

proxy measure was used. The occupation classification was based on the

International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO88) which

classifies jobs into occupational groups according to the similarity in

the skill level and the skill specialisation of the tasks and duties

performed. For convenience purposes the “Major”

ISCO grouping was used which is quite broad. It merges many occupations

together and doubtlessly conceals many important details.

The father’s

occupation was chosen because father is often regarded as the head of

household. However, there are many single parent families in Montserrat

where the mother is the sole provider. Omitting the mother’s

occupation may exclude relevant information and introduce bias [7]. In

this study the children of professional fathers had lower caries

prevalence than children of non-professional fathers (Table 5).

Socioeconomic status has been linked with oral health status and indeed

there is evidence that persons of lower socioeconomic status often have

worse health than persons of higher socioeconomic status [8].

This introduces the concept

of

a social gradient in health that has been expressed by many

researchers. It refers to the fact individuals at the top of the social

strata have better health than those immediately below them on the next

strata and this continues down the social scale or employment hierarchy

[9 Sheiham and Watt 2000].

These authors reported that

from 1978-1988 the mean number of decayed teeth in social classes IV

and V in the UK was 1.8 compared with 0.8 in the upper social classes.

This disparity in caries

experience between children from higher and lower socioeconomic

households although not quite marked should be monitored or explored

further. It is important that any gap be closed and that those at the

lower end are not disadvantaged by inequalities.

Quality of Life

The quality of life data

showed

most children regarded their oral health as “good”

or better. They also reported a low level of oral symptoms despite

having increased levels of functional limitations. This was interesting

to note. One explanation could be that the children did have

significant oral symptoms but had managed to cope with them. Blaxter

reported that 71% of persons with health problems described their

health as good or excellent in the National Health and Lifestyles

Survey [10 Blaxter 1990].

Social

determinants/Inequalities

Many researchers now focus

on

social determinants. It is thought that the broader determinants such

as economic and environmental factors have far reaching influence

ultimately affecting individual habits and behaviours. Good oral

hygiene habits and dietary practices will flourish in a supportive

environment, where such practices are the norm, where family and

community networks can shape habits and persons have access to

essential service and goods necessary for maintaining acceptable

standards of living and sustaining the good habits [11 Watt 2005].

Poor living conditions,

lack of

housing, unemployment, educational attainment are all causes of health

disparities. While it was not the aim of this study to explore the

reasons for the differences in oral health the following are points for

consideration:

- There has been severe

economic

downturn coupled with a rising cost of living following the volcanic

disaster.

- Many persons are still

facing

housing concerns having lost homes or having been forced to abandon

homes

- Small numbers of persons

are

living in volcanic housing developments which are in need of

restoration.

However, it can be argued

that

area deprivation is not a valid indicator as the entire population is

now dwelling or living in a more defined area of the country which can

be regarded as more homogenous. The essential action is to unearth the

“causes of the causes” [12 Sheiham and Watt 2003].

Oral health data from a

study

in New Zealand revealed significant association between higher caries

experience of an individual at age 26 and low paternal socioeconomic

position [13 Poulton et al. 2002]. This shows that adverse events in

childhood can have the impact later in life [14 Bartley et al. 1997].

Equally an argument can be made for positive interventions early in

life with the aim that later outcomes should be positive.

Significance of CPQ

The other concerns of the

children such as difficulty eating, being self conscious about

appearance should be considered. At face value they may not be regarded

as life threatening and could easily be dismissed by health planners

particularly when compared with conditions such as diabetes melitus and

cardiovascular disease. Quite a high percentage of children reported

feeling upset or nervous but these concerns are more personal in nature

and do not necessarily have a major impact on the society. Health

planners are challenged with convincing relevant authorities that these

valid concerns requiring attention. In fact they are all components of

the pubic health problem of dental caries. The challenge comes with

attempting to quantify, directly measure or assign a value or weight to

such concerns for the benefit of funding agencies or financial

departments who evaluate things in dollars and cents. Perhaps if these

concerns are quantified in terms of days lost from school, or in the

case of an adult days lost from work then the threat to economic

stability can be better assimilated or judged by those in authority.

While lowering the DMFT

will be

desirable and will provide a global indicator of the health status it

maybe of more value to the patients being served to be painfree, to be

able to eat without difficulty and to be able to work well in school.

These results can inform planning goals, objectives or more

specifically become outcome indicators.

Those children with higher

caries experience reported a greater impact on their QoL. This

difference was almost twice as much than those who were caries-free.

Although no significance testing was performed these results are

similar to the findings of other studies which highlight the impact of

oral disease on daily activities. Older adults in South Australia

reported greater levels of social impact on quality of life as a result

of being edentulous [15 Slade and Spencer 1994] .

Public Health Strategies

The success of salt

fluoridation in Jamaica [16] and proven effectiveness of water

fluoridation [17] lend support to adopting these options in Montserrat.

However, with a mean DMFT score of 1.91 at age 12, it may not be

justifiable to implement these programmes without further detailed cost

benefit analysis. It maybe equally worthwhile to evaluate current oral

health interventions, make modifications which are scientifically sound

before implementing these population based strategies. A combination of

oral health promotion activities (dental education, toothbrushing

campaigns) and restorative care for all, together with services

directed at those children at higher caries risk could be implemented.

A valid and feasible

strategy

for tackling this problem and convincing financial bodies whether

governmental or non-governmental is to implement the Common Risk Factor

Approach (CRFA) [9]. In this way several public health diseases are

simultaneously targeted by dealing with a few common risk factors. In

this instance diet is the risk factor for dental caries as well as for

diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease. Such a strategy involves

collaborative partnerships with other health and governmental

departments.

Study Limitations

A response rate of 69% was

achieved in this study. A better response rate would have been more

desirable given the small population size. However, study criteria

regarding consent had to be adhered to. Omitting the 14 children who

failed to return consent letters would likely result in omission of

important details and introduce bias. The small numbers also made it

difficult to perform any meaningful statistical analysis. Using

occupation as a measure of socioeconomic status could have been

limiting as it fails to acknowledge other dimensions (educational

level, income).

Conclusion

It is difficult to compare

Montserrat’s DMFT of 1.93 with that of regional islands as

the data was collected at different periods (Refer to Table 1). Many of

the islands have scores range from 0-6 suggesting that Montserrat is

not differing greatly or experiencing greater disparity than its

regional neighbours. It is important not to fall behind. Despite this

there is no place for complacency as high levels of untreated decay

exist amongst 12-year-olds in Montserrat. This indicates that there is

a need for restorative care from the professionals as well as an

existing need for care by the individual. This gap between the

professional need and patient need needs to be bridged. The barriers

preventing this must be identified. It could be something easily

identifiable such as fear, issues of accommodation or something more

complex as patient perception of illness and disease.

The low Care Index suggests

that the current service is falling short in their mission of providing

health to the community. Remuneration is via a salaried payment system

and one of the faults of such a system is under-treatment. This is just

one of many possible explanations being proffered.

Small numbers make it

difficult

to ascertain any differences between male and female oral health but

this can be monitored to ensure that no inequalities are created.

It is not apparent what

role,

if any, the social and environmental determinants within the community

are playing in disease causation. It is also not certain whether

economic downturns and housing issues are factors but further research

will have to be done on this.

Children are experiencing

significant disadvantage as a result of oral conditions or disease.

This should not be ignored or trivialised. Inequalities between

children of different socioeconomic status is evident from the study

but difficult to determine significance.

Recommendations

Montserrat should aim to

develop a comprehensive oral health policy as a matter of priority.

Special emphasis could be given to oral health of young persons.

Current oral health practices and policies need to be evaluated and

modified where necessary. The community, general health departments and

other stakeholders should be engaged in the policy development. The

benefit of conducting a health needs assessment should not be ignored

provided resources are available. The results of this study can serve

as a foundation for persuading health authorities to give oral health

greater priority and can guide general and local clinic policy

development or decisions. Additional surveys of children should be

performed for 5 and 15 year olds to get a more balanced representation

of the state of children’s health. A move towards more

evidenced-based dentistry is necessary. Broad areas for attention

include diet, dental education and toothbrushing programmes in

supportive environment. Urgent attention needs to be given to children

with active caries. This could be part of a targeted approach discussed

earlier. Adopting a CRFA toward health is highly recommended and this

necessitates collaborative partnerships with health departments. In the

long-term dental health providers should work with other governmental

departments to influence school nutrition policies, food importation

and production regulations and consumer education with respect to

healthy food choices. The government has a responsibility to ensure and

maintain acceptable living standards by reducing social, economic and

environmental and inequalities. Health is political.

References

1. Pine CM,

Pitts NB,

Nugent

ZJ. British association for the study of community dentistry (BASCD)

guidance on the statistical aspects of training and calibration of

examiners for surveys of child dental health. A BASCD coordinated

dental epidemiology programme quality standard. Community

Dental Health

1997; 13 (Suppl 1): 18-29.

2. Pine C,

Burnside G.

BASCD

Trainers’ Pack for caries prevalence studies.

University of

Dundee, Dundee 2004.

3. Nuttall N

M. Capability

of

national epidemiological survey to predict General Dental Service

treatment. Community

Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology

1983; 11: 296-301.

4.

Okeigbemen SA. The

prevalence of dental caries among 12 to 13-year-old school children in

Nigeria: report of a local survey and campaign. Oral

Health and

Preventive Dentistry 2004; 2:

27-31.

5. Pitts NB,

Chestnutt IB,

Evans D, White D, Chadwick B, Steele JG. The dentinal caries experience

of children in the United Kingdom, 2003. British

Dental Journal 2006;

200: 313-320.

6. White DA,

Chadwick BL,

Nuttall NM, Chestnutt IG, Steele JG. Oral health habits amongst

children in the United Kingdom in 2003. British

Dental Journal 2006;

200: 487-491.

7. Zurriaga

O,

Martinez-Beneito

MA, Abellan JJ, Carda C. Assessing the social class of children from

parental information to study possible social inequalities in health

outcomes. Annals of

Epidemiology 2004; 14: 378-384.

8. Watt R,

Sheiham A.

Inequalities in oral health: a review of the evidence and

recommendations for action. British

Dental Journal 1999; 187(1):

6-12.

9. Sheiham

A, Watt RG. The

common risk factor approach: a rational basis for promoting oral

health. Community Dentistry

and Oral Epidemiology 2000; 28:

399-406.

10. Blaxter

M. Health and

Lifestyles 1990; London:

Routeledge.

11. Watt RG.

Strategies and

approaches in oral disease prevention and health promotion. Bulletin

of

the World Health Organization

2005; 83(9): 711-718.

12. Sheiham

A, Watt RG.

Oral

health promotion and policy, in Murray JJ, Nun JH, Steele JG (ed.)

Prevention of Oral Disease

2003; 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University

Press, pp. 245.

13. Poulton

R, Caspi A,

Milne

B, Thomson W, Taylor A, Sears M, Moffitt T. Association between

children’s experience of socioeconomic disadvantage and adult

health: a lifecourse study. The

Lancet 2003; 360(9346):

1640-1645.

14. Bartley

M, Blane D,

Montgomery S. Socioeconomic determinants of health Health and the life

course: why safety nets matter. British

Medical Journal 1997;

314: 1194-1196.

15. Slade

GD, Spencer AJ.

Development and evaluation of the oral health impact profile. Community

Dental Health 1994; 11: 3-11.

16.

Estupiñán-Day S, Baez R, Horowitz H, Warpeha R,

Sutherland B, Thamer M. Salt fluoridation and caries in Jamaica.

Community Dentistry and Oral

Epidemiology 2001; 29(4):

247-252.

17. McDonagh

MS, Whiting

PF,

Wilson PM, Sutton AJ, Chestnut I, Cooper J, Misso K, Bradley M,

Treasure E, Kleijnen J. Systematic review of water fluoridation.

British Medical Journal

2000; 32: 855-859.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the

students

who participated and their parents who consented.

The support and assistance

of

the principal and staff of the Montserrat Secondary School and the

Ministry of Education Health and Community Services were beyond

expectation.

Special thanks to the staff

of

the St. John’s Dental Clinic who assisted ably and

efficiently with examinations.

Thanks to Supervisors Dr

Nick

Kendall, Prof. Tim Newton and Dr. Blanaid Daly whose combined input was

invaluable and greatly appreciated.

©

Coretta

E. Fergus

HTML

last

revised 18th June, 2009.

Return

to

Conference

papers.