The truth is that our finest moments are most likely to occur when we are feeling deeply uncomfortable, unhappy or unfulfilled. For it is only in such moments, propelled by our discomfort, that we are likely to step out of our ruts and start searching for different ways or truer answers – M Scott Peck.

And there comes a time, when one must take a position that is neither safe, nor politic, nor popular – but, one must take it, simply because it is right – Martin Luther King Jr.

This paper reflects on Montserratness and the role it plays in sustainable development. It argues the spill-off of settlement in a ‘foreign’ land is eating away at Montserratness and have left it exposed to multi-cultural and neo-political elements that seem to deny it an ‘identity space’. What is evolving is a recreated brand of ethics from among shifting principles and values at home, but more so abroad. I refer specifically to the United Kingdom (UK) diaspora. The paper views Montserratness as an integral part of the national development equation. It explains how the post-1995 migrants together with their post-war counterparts are struggling to sustain Montserratness in a ‘foreign’ Motherland. Admittedly, this is an uphill struggle since the Montserrat identity is being squashed, and sometimes made invisible, due to the pressures from the more dominant cultures in this multi-ethic, multi-cultural metropolis. Despite the challenges, Montserratness is still being celebrated and the desire to sustain an island identity remains strong.

It is impossible to acknowledge and mark a ten-year milestone (1995-2005) as the period of volcanic activity and as relocated migrants, without celebrating Montserratness. Unquestionably, there are several issues that surface in respect of our individual, cultural and national identity. We run the risk of ignoring them if we are unclear about what we treasure, about our values, about being Montserratians and about what give us stability as a relocated clan. To address these issues then is to examine fully what beliefs and actions typify personhood and nationhood. It thus becomes necessary to celebrate Montserratness in a way that it not only becomes engraved in the psyche of the post-1995 diaspora (particularly those born in the UK), but is also manifested in their actions. Such actions should embrace change and ‘newness’, open-mindedly, purposefully and resolutely. It is in this way that relocated migrants and their post-war counterparts are able to sustain their Montserrat identity.

The next strand of this paper looks at sustainable development. A widely accepted explanation of this term comes from the Brundtland Report 1987, also known as ‘Our Common Future’. The report defines sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (ACE 2008). The report identifies environmental protection, economic growth and social equity as the three underlying factors of sustainable development. This suggests that within the confines of the named components, if present needs are met sustainable development is possible. The operative phrase to note is: ‘ability of future generations’ since development by any measure suggests activity and mobility, which are crucial practices for successive generations. How these generations advance is rather important if via sustainable development the quality of life of each individual is to be improved. If Montserrat is to embrace Brundtland’s conceptualisation, if it is to procure a better quality of life for Montserratians and residents now and in the future, then it becomes an imperative to encourage a sustainable level of Montserratness regardless of where relocated migrants now reside.

A preliminary review of the Montserrat Development Plan (SDP) 2003-2007 showed this as one of the main strategic objectives: “to promote the retention of present population & the return of Montserratians from overseas” (Daley 2007). All efforts to achieve this aim should evoke a cogent and dynamic integration of returnees into the social, political and economic milieu in Montserrat. Such large-scale repatriation raises several issues relating to Montserratness – what was, what is and what is evolving. It also provokes thoughts about national development. At the risk of being ethnocentric, I deem these as important quests since the way of life that is handed down from generation to generation, artefacts, shared beliefs, ideas and behaviours are cultural elements which are at the core of human development and survival.

Clearly, the demographics in Montserrat have changed considerably since 1995. In a similar vein, the UK diaspora have undergone transformation of all sorts, hence the need for attitudinal changes with respect to accommodating ‘newness and change’ if the SDP objective is to be achieved. Changing in attitudes is not a one-sided affair. Returnees and current residents alike should be willing to rethink their positions on what characterise present-day Montserrat and its current mores, values and standards. Such a rethink is necessary because for some members of the diaspora, Montserratness is a mental construct. They have fixed images in their minds about what was, thus inadvertently opening themselves to consternation and disappointments on their return. This condition is not unique to relocated Montserratians for Safran notes this as a common feature among other resident migrants: “they retain a memory of, a cultural connection with, and a general orientation towards the homeland”.

Comparatively, there seem to be a reluctance among some resident Montserratians to acknowledge that returnee migrants have too moved on and would not readily return to ‘old ways’, if ever. What is needed for national development is a merging of ideas into a single sum total with various branches and offshoots, having sustainable development as the denominator and Montserratness as the intersection.

Given that a sustainable level of Montserratness is crucial to Montserratians’ livelihood amidst a multicultural ‘throng’, it follows then that those very dynamics are necessary for returnees’ ‘survival’ among islanders who have undergone changes on various levels, at varying degrees, in a metamorphosised homeland. But what does Montserratness really mean?

“…a system of beliefs, values, and modes of construing reality that is shared by a group or society” (Saljo 1994: 1242).

From among the many conceptualisations offered to explain culture, I have handpicked the above explanation for this discussion because it provides a useful platform from which notions of Montserratness can be launched.

What constitutes Montserratness is inextricably linked to the aforementioned cultural element, thus Montserratness is directly related to ‘possessing’ the Montserrat culture. It almost seems incongruous for Montserratians to claim a culture since their shared beliefs and behaviours are plaited with African, Irish, British and Caribbean influences. Yet, the mix that has evolved is prototypically Montserratian. The essence of Montserratness is captured in maroons,1 ‘box hands’,2 calypsos, steelbands, masquerades3 and string bands.4 It is also manifested in dressing in one’s ‘Saturday and Sunday best’, the ‘strangers’ paradise’ hospitality, ‘the-morning-neighbour-morning’ greeting, the communal joys and sorrows’ and an exciting ‘Montserrat English’ (dialect). There is no Montserratness without these Irish legacy: the Shamrock, the Lady and the Harp, St Patrick’s Day, goat water, surnames such as Allen, Bramble, Dyer, O’Brien, O’Garro, Riley and Tuitt.

An embedded strand of Montserratness is a ‘sense of place’, which by extension, includes a strong attachment to land – ‘a piece of the rock’. This steadfast connection is riveted to a strong island identity. Skinner (1999: 1), in commenting on the devastation caused by the volcanic activity, remarked that the result is a “literal destruction of Montserratians’ sense of place”. From my vantage point as a member of the UK diaspora, this great loss has openly exposed two plain truths: (1) an acknowledgement that the loss has broken a link in the circle of Montserratness; and (2) Montserrat is still the reference point for individual and group identities. The questions this raises are: in light of these truths, what are the implications for sustainable development? Has life in the ‘foreign’ nurtured a mindset for repatriation?

I first take issue with the phrase ‘foreign motherland’. ‘Foreign’ and ‘mother’ do not cohabit in the same sentence, thus making the expression an oxymoron. Yet, on account of Montserrat’s present and past political status and because of negative circumstances surrounding settlement after relocation (Shotte 2002; Shotte 1999), I employ the phrase to describe the overall situation. It is on this basis that I offer three frames within which ‘foreign Motherland’ should be interpreted:

This paper does not allow space for an in depth analysis of the above frames. However, it does provide a peek into the general circumstances that influence relocated migrants’ lifestyle and the conditions that affect the maintenance of Montserratness. There are several variables that impinge on our understanding of what Montserratness means in a Motherland context. Neither the constitution, nor the education curriculum is helpful in this respect. In fact it is these very British heirlooms that seem to attack our sense of ‘islandness’ and blur the demarcation lines between what we deem right and wrong, thus the identity warfare continues.

Montserratians had always sported plural identities, which are dictated by particular circumstances. For example, a Montserratian can be identified as a Leeward Islander, a ‘small islander’, an Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) representative, a Caribbean Community (CARICOM) ambassador or even a British Overseas Territories (BOT) envoy. And more recently, a British Citizen delegate was added to the list. The issue here is, can we still celebrate a ‘pure’ Montserrat identity? Admittedly, relocation to the UK has forced a re-examination of our political status and social orientation. The ‘big fishes in a small pond’ expression is now been viewed as ‘small fishes in a big pond’ construction. What might have been accepted as ‘comfortable’ shifting identities are now been constantly contested in the ‘foreign’.

In order for migrant ethnic groups to withstand the pressures of culture clashes, retention of memory of the homeland is not enough. Safran (2004: 10) found these other actions to be quite crucial:

The above proved essential for the UK diaspora. The Montserrat Government UK Office together with the UK Montserrat Organisations,5 religious leaders and other concerned Montserratians have organised education workshops and many social events. It is via these activities that Montserratness is celebrated. The following comment aptly captures the quintessence of these gatherings:

They came in their hundreds, braving the ‘cold front’ that had dumped almost a foot of snow on the ground. They came to celebrate, as only Montserratians can… While the activities in some way mirrored those on the Emerald Isle (Montserrat), the joy and fellowship of the dispersed could not be duplicated. The level of patronage of these activities is proof of their value (Montserrat Community Support Trust (MCST) 2001: 1)

To brave the ‘cold front’ to come together as a community to celebrate Montserratness does show how very important culture maintenance is for survival in a ‘foreign Motherland’. This is not simply another occasion to socialise but rather a communal acclamation of Montserratness. It is suchlike cultural creative activities that are useful to the post-1995 diaspora in helping it to deal with the ‘streets of gold’ disappointments, to live with racist attitudes, to understand the chaos and empty promises, to cope with stringent bureaucratic practices, to cushion the culture shock, to grapple with social harassment and embarrassment and to see the ‘frills and thrills’ for exactly what they are.

Living in cultural environment as diverse as that of the UK necessitates a redefining of ‘Montserratness’. I contend that a ‘new’ brand of ethics has evolved over the years within a dynamic process of development, which includes vacillating between ‘traditional’ Montserratness and the new ‘local’ within a global setting.

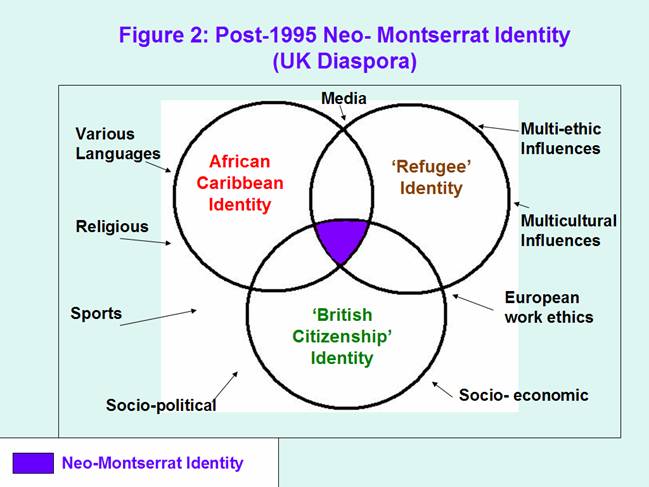

Elsewhere I argued that relocated Montserratians’ new concepts of time, space and distance were framed within an ‘expanded’ British environment where rules and restrictions are ‘written in stone’, where bureaucratic practices demand ‘excessive paper work’, and where their ethnic identity exposes them to racial discrimination (Shotte 2006; Shotte 1999). With regards to education practices, I also pointed out that an African Caribbean identity, in particularly Jamaican, was thrust upon them by a system that had little, and sometimes no regard for their Montserratness. An acquired quasi refugee identity and the British Citizenship identity have also taken their toll on relocated migrants’ sense of their homeland identity. And although over time the diaspora have managed to craft new ways and means to deal with identity challenges, eventually bits and pieces of ‘otherness’ from other ethnic and cultural influences trickled ‘traditional’ cultural defences – home-grown attitudes and values.

The changes in lifestyle and habits are quite evident - European countries, especially France, are the new Antigua; gang and youth cultures are ‘extra-curricular’ activities; work ethics are governed by the ‘printed’ rather than the practical; the availability of a 999 and/or 0800 1111 telephone service to children who refused to be disciplined by their parents/guardians; and opportunities to flaunt one’s human rights. Additionally, many relocated migrants have taken the opportunities offered for getting certified in just about every vocation possible, including academic careers. Although for some people pastimes are quite similar to those in the homeland, they are played out in a different context thus giving them a new look and new meaning. Consider too the skilled young Montserratian drivers who have taken a fancy to Formula One habits despite the absence of a formal racetrack. These are just some of the practices out of which a neo-cultural philosophy is emerging.

Hall, in Woodward (1997: 51) asserts that identity should not be considered an accomplished fact, but rather as a production which is never complete, always in process. Gilroy puts forward a similar sentiment:

The raw materials from which identity is produced may be inherited from the past but they are also worked on, creatively or positively, reluctantly or bitterly, in the present (Gilroy 1997: 304).

Inevitably, in light of the foregoing, a redefinition of self and identity is crucial for survival in host country Britain. Yet, it is imperative that the core culture that Montserratian-born Alphonsus ‘Arrow’ Cassel encouraged Montserratians to be “proud of forever”, be positioned in first place on the neo-culture agenda. The Montserrat dialect must remain an integral part of the Montserrat identity. I therefore advocate that a cultural shift is unavoidable. The blending of the traditional and the ‘new’ is a necessary combination for not only the redefinition of Montserratness in an expanded geographic and philosophical setting, but also for the maintenance of core cultural values.

Refugees are going home. But to what? For many people, the trauma of being driven from one’s home will now be matched by the shock of returning to a home that does not exist (Levy 1999 in Oxfeld & Long 2004: 11).

Levy views home as ‘actual place of lived experience’. Other perspectives come from Armbruster who sees home as “a metaphorical space of personal attachment and identification” (Armbruster 2002: 20) and Brah as “a mythic place of desire” (Brah 1996: 192). Papastergiadis (1998, in Al-Ali & Koser 2002: 7) offers yet another viewpoint: “a place where personal and social meanings are grounded”. And Fabos (2002: 34-50) takes a symbolic position – home is conceptualised as being in the making of tradition and culture, and by extension notions of identity and belonging.

Taking all of the above explanations as given, relocated migrants who intend to make the SDP objective mentioned earlier a reality, will return with these, and perhaps more notions of home. But whatever positions taken, migrants will return with a mindset that is influenced by their numerous life-changing experiences that had while abroad. The neo-cultural philosophy that is being crafted in host country will have an influential bearing on their decisions and actions. The resilience that defined Montserratness in the wake of category-5 Hurricane Hugo and the volcanic crisis, while still very evident, resides on a different plane, in a different context, under different circumstances. The pertinent question is: Is Montserrat ready to accommodate a neo-cultural philosophy within its sustainable development programme? Another issue this raises is: Are returnees prepared to make the personal and social adjustments necessary to effect progress? Will returnees and residents be willing to find a common element that would facilitate co-habitation, assist in the fight to overcome obstacles and make the sacrifices necessary to improve the quality of life for present and future generations?

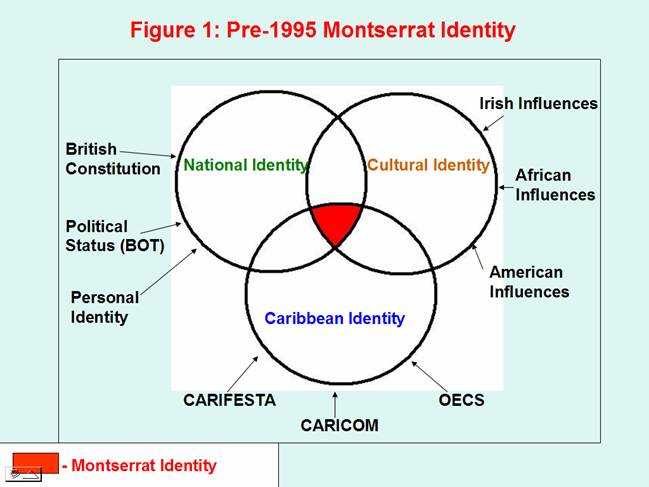

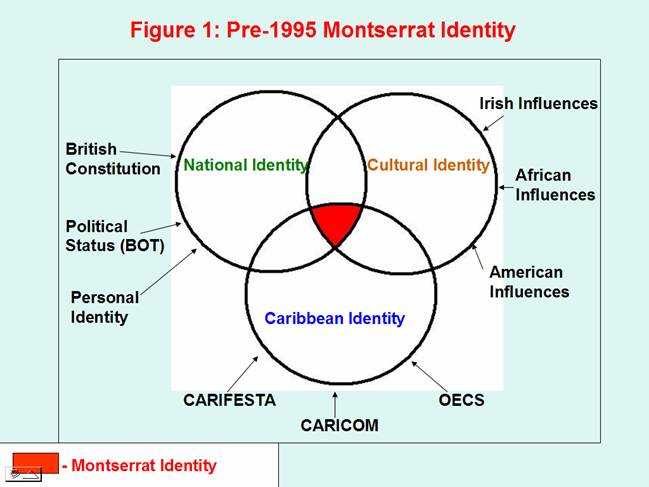

I offer two models (Figures 1 & 2) that should provoke debate on how to move towards sustainable development by merging pre and post-1995 circumstances that influence identity. They do not boast a complete representation of circumstances, but they do provide insight and shed some light on the likely influences that have impacted on personal and national development.

Out of Figure 1 emanates a resilient, solid, proud, ‘ostentatious’, home-grown spirit encased by a cultural heritage that defies man-made and natural disasters. From Figure 2 come prowess, fortitude, resilience, determination, character and pluck within a neo-cultural identity that embraces calculated triumph and gratification as much as it does measured regrets and disappointments. Admittedly, finding a common space with a neat fit for all the noted attributes is indeed challenging. But does challenging means impossible? The ‘trial and failure’ idiom is necessary here.

It is perhaps instructive that the focus on sustainable development at this time is in keeping with the goal of the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (UNDESD) - 2005-2014: “to integrate the principles, values, and practices of sustainable development into all aspects of education and learning” (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) 2008). It is hoped that via education it is possible to effect changes in behaviour with regards to “environmental integrity, economic viability, and a just society for present and future generations”.

The UN’s stamp on any mandate clearly demonstrates that the issues concerned are of a global nature. However, it is Montserrat’s responsibility to develop its own strategies and processes to address the wide-ranging issues that relate to sustainable development in a local and national context. To this end, there is no need to reinvent the wheel. UNDESD not only invites countries to learn from each other’s experiences but also to share their good practices. Table 1 highlights Good Practice 7 from the Regional Environmental Centre (REC) for Central and Eastern Europe. What I offer for consideration is: how can the Montserrat government utilise returnees’ expertise alongside residents’ proficiencies in analysing the procedures shown in Table 1 with a view to constructing effective strategies that can be shared? I contend that the neo-cultural orientation that returnees bring to the home field is a workable catalyst for sustainable development.

|

|

|

| "Good practices in ESD" are initiatives closely related to Education for Sustainable Development, that demonstrate good practice, generate ideas and contribute to policy development. These good practices: | |

| 1. |

Focus on the

educational

and

learning dimensions of sustainable

development. |

| 2. |

are innovative. They

develop

new and creative solutions to common

problems, such as:

|

| 3. | make

a difference. They

demonstrate a positive and tangible

impact on the living conditions, quality of life of the individuals,

groups or

communities concerned. They seek to bridge

gaps between different societal actors/sectors and are inclusive, in

order to

allow

new partners to join the implementing

agents/bodies. |

| 4. | have

a sustainable

effect.

They contribute to sustained

improvement of living conditions. They must integrate economic, social,

cultural and

environmental components of sustainable

development and reflect their interaction/interdependency in their

design and

implementation. |

| 5. | have

the potential for

replication. They provide

effective

methodologies for transdisciplinary and multi-sectoral cooperation.

They serve as models for

generating policies and initiatives

elsewhere. |

| 6. | offer

some elements of

evaluation. They have been and

can be

evaluated in terms of the criteria of innovation, success and

sustainability by both

experts and the people concerned. |

This paper explores Montserratness and what it means for sustainable development. It posits that with regards to the UK diaspora, core traditional cultural habits have evolved into a neo-cultural identity. Despite the challenges that post-war and relocated migrants face, Montserratness is still being celebrated. It offers two models that illustrate how different forces impact on personal and national development. Montserratness is viewed as an integral part of sustainable development and education is seen as a useful agent that can assist residents and returnees alike to share in developing ‘good practice’ strategies for sustainable development.

While not claiming a ‘complete’ picture, the paper deems the post-1995 time in ‘exile’ a sufficient period to provide some indication and insight into the ‘identity’ experiences of relocated migrants. To link Montserratness to sustainable development is a step in the right direction. I deem the emergence of a neo-cultural identity as more than an ethnic cliché – I perceive it as an entire ensemble of cultural ideology that includes perhaps, as its most intangible trait – transience.

1 A ‘maroon’ is “the voluntary co-operative activity of a number of persons who combined to assist one or more persons in a particular task. Typical tasks were the building or moving of a house, the preparing of land for planting and the harvesting of a big crop” (Fergus 1994: 258).

2 ‘Box hand’ is the term given to a rotating credit association. A central organiser collects and distributes fixed amounts to members of the ‘box hand’ on a weekly basis. For example, if there are 25 persons in the ‘box hand’, an individual weekly take at £10 per week is £250. The organiser arranges the order of collection. Membership and weekly deposits vary according to the mutual agreement of the organiser and the persons involved.

3 These masked dancers in colourful costumes have employed a mixture of ethnic influences to create what has now been generally recognised as a Montserrat tradition. To explain, the Masquerade’s outfit resembles the Belizean and Jamaican jonkonnu, the musical ensemble consists of the Irish fife and the African kettle-drums, a boom drum, a boom pipe, and a shak-shak. The folk religion and drum beat are African, while the quadrille and the polka (dance steps) are Irish. The dancers also dance to folk songs that are created from Caribbean experiences. Noticeably, there is an overall weightier African influence in this interpolation. Little wonder that Fergus hails the Masquerades as “the richest expression of African folk art in Montserrat” (Fergus 1994: 242).

4 A folk band that features the Hawaiian ukelele.

5 These include Montserrat London Forum, The Montserrat Community Support Trust (MCST), Hackney Montserrat Association, Keep Montserrat Alive, Montserrat Action Community 89 (MAC89), Montserrat Overseas Progressive People’s Alliance (MOPPA), Haringey Parental Outreach Team and various church groups.

ACE (2008) Brundtland Report, retrieved from www.ace.mmu.ac.uk, accessed on 25/09/08.

Al-Ali, N. & Koser, K. (2002) “Transnationalism, International Migration and Home”, in N. Al-Ali & K. Koser (Eds.) New Approaches to Migration? Transnational Communities and the Transformation of Home, London: Routledge, pp.1-14.

Armbruster, H. (2002) “Homes in Crisis: Syrian Orthodox Christians in Turkey and Germany”, in N. Al-Ali & K. Koser (Eds.) New Approaches to Migration? Transnational Communities and the Transformation of Home, London: Routledge, pp.17-33.

Brah, A. (1996) Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities, London: Routledge.

Daley, A. (2007) Preliminary Review of the Montserrat SDP 2003 – 2007, Brades: Economic Development Unit.

Fabos, A. (2002) “Sudanese Identity in Diaspora and the Meaning of Home: The Transformative Role of Sudanese NGOs in Cairo”, in N. Al-Ali & K. Koser (Eds.) New Approaches to Migration? Transnational Communities and the Transformation of Home, London: Routledge, pp.34-50.

Fergus, H. (1994) Montserrat: History of a Caribbean Colony, London: The Macmillan Press Ltd.

Gilroy, P. (1997) “Diaspora and the Detours of Identity”, in K. Woodward (Ed.) Identity and Difference: Culture, Media and Identities, London: Sage Publications Ltd., pp. 299-346.

MCST (2001) “For Culture’s Sake”, in MCST News, Volume 3, Issue 1, May 2001.

Oxfeld, E. & Long, L. (2004) “Introduction: An Ethnography of Return”, ”, in L. Long & E. Oxfeld (Eds.) Coming Home? Refugees, Migrants, and Those Who Stayed Behind, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp.1-18.

Safran, W. (2004) “Deconstructing and Comparing Diasporas”, in W. Kobot, K Tololyan and C Alfonso (Eds.) Diaspora, identity and religion: New directions in theory and research, London: Routledge, pp.9-30.

Saljo, R. (1994) “Culture and Learning”, in T. Husen & T. Postlewaite (Eds.) International Encyclopaedia of Education, Oxford: Pergamon, pp.1241-1246.

Shotte, G. (2006) “Identity, Ethnicity and School Experiences: Relocated Montseratian Students in British Schools”, Refuge, 23 (1): 27-39.

Shotte, G. (2002) Education, migration and identities: Relocated secondary school students in London schools, Unpublished PhD Thesis, Institute of Education, University of London.

Shotte, G. (1999) “Islanders in transition: The Montserrat case”, Anthropology in Action, 6 (2): 14-24.

Skinner, J. (1999) “Island Migrations, Island Cultures”, Anthropology in Action, 6 (2): 1-5.

Woodward, K. (1997) “Concepts of Identity and Difference”, in K. Woodward (Ed.) Identity and Difference: Culture, Media and Identities, London: Sage Publications Ltd., pp. 7-62.

UNECE (2008) “Good practice” in education for sustainable development in the UNECE Region, retrieved from http://www.unece.org.uk, accessed on 25/09/08.

UNESCO (2008) Education for Sustainable Development, retrieved from http://www.unesco.org.uk, accessed on 25/09/08.

HTML last revised 18th June, 2009.

Return to Conference papers.