Figure 1: Child and Adolescent Treatment Model (CATM) by Katheryn L. Whittaker

The Americas, due to geographical location, are constantly threatened by hurricanes. Each year during June to November, all Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coast-line areas, as well as miles of inland, are subject to tropical storms and catastrophic hurricanes (FEMA, 2006). The 2005 Season proved to be the worst in recorded history in terms of numbers, intensity of systems, and areas grossly impacted. The northern islands of The Bahamas were hit repeatedly by hurricanes.

A great deal has been said about the effects of hurricanes, the destruction and the devastation they leave along their pathways (Ministry of Health & The Public Hospitals Authority, 2004). Much effort has been poured into the repair and the rebuilding of the physical and material structures of the affected areas. The scope of these efforts often spans local, national, and international initiatives (Caribbean Net News, 2005; USAID, 2004; MOFA, 1999). In fact foreign governments are on record of having contributed large amounts of financial (USA $22,576,847 to the Caribbean and Japan 9,500,000 yen to the Bahamas), as well as technical and material resources (USAID, 2005; MOFA, 1999). The psychological and emotional disrepair of hurricane survivors appeared to have limited attention beyond the initial alleviation of distress and the grief associated with the losses suffered.

There is a need to channel more effort and resources into repairing and rebuilding the psychological and emotional damages imposed upon hurricane victims. Drescher and Abueg (1995), call for more PTSD field research in hurricane disaster victims. Following the 2004 hurricane season, health professional asserted that "the most effective approach is that of looking at a whole person. We are body as well as mind. Therefore, if we focus on the physical . . . and neglect the mental health and emotional stability, then we cannot say that the person is totally healthy. A state of complete wellness is needed, if persons are expected to function at their full capacity or fulfill their maximum potential" (The Nassau Guardian, 2004). Like partly demolished structures that remain unattended, they further deteriorate, lose their utility and become a danger to self and others, so too are the lives of unattended survivors who suffered battering from the psychological and emotional storms of enduring a hurricane.

Traumatized individuals are at risk for developing stress related symptoms and if unresolved they may progress to the condition known as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). According to the DSM-IV-TR (2000), an individual with PTSD must have experienced a traumatic event that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or threat to physical integrity. The individual's response to this event includes intense fear, helplessness or horror. In the case of children there is disorganization and agitated behavior. PTSD symptoms are categorized into three clusters: These include a) the reliving of the event such as flash backs and intrusive images, b) avoiding reminders of the event such as activities, places, thoughts and people, and c) increase arousal with irritability, hyper-vigilance and impaired concentration.

Optimal mental health however is a state of wholeness for the individual, whose psychosocial well-being is intact, and the individual not only appears well but is also functional. Psychosocial Health refers to being mentally, emotionally, socially, and spiritually well. Mental health refers to thinking, emotional health refers to feelings, social health refers to relating and spiritual health refers to being (Donatelle, 2002).

Often buildings that have weathered the forces of hurricanes appear to be relatively intact; however, a closer examination by a structural engineer would render it shaky, and structurally unsafe. Hurricane survivors could appear to be "holding it together" but a closer assessment by helping professionals may reveal the presence of much distress and emotional trauma.

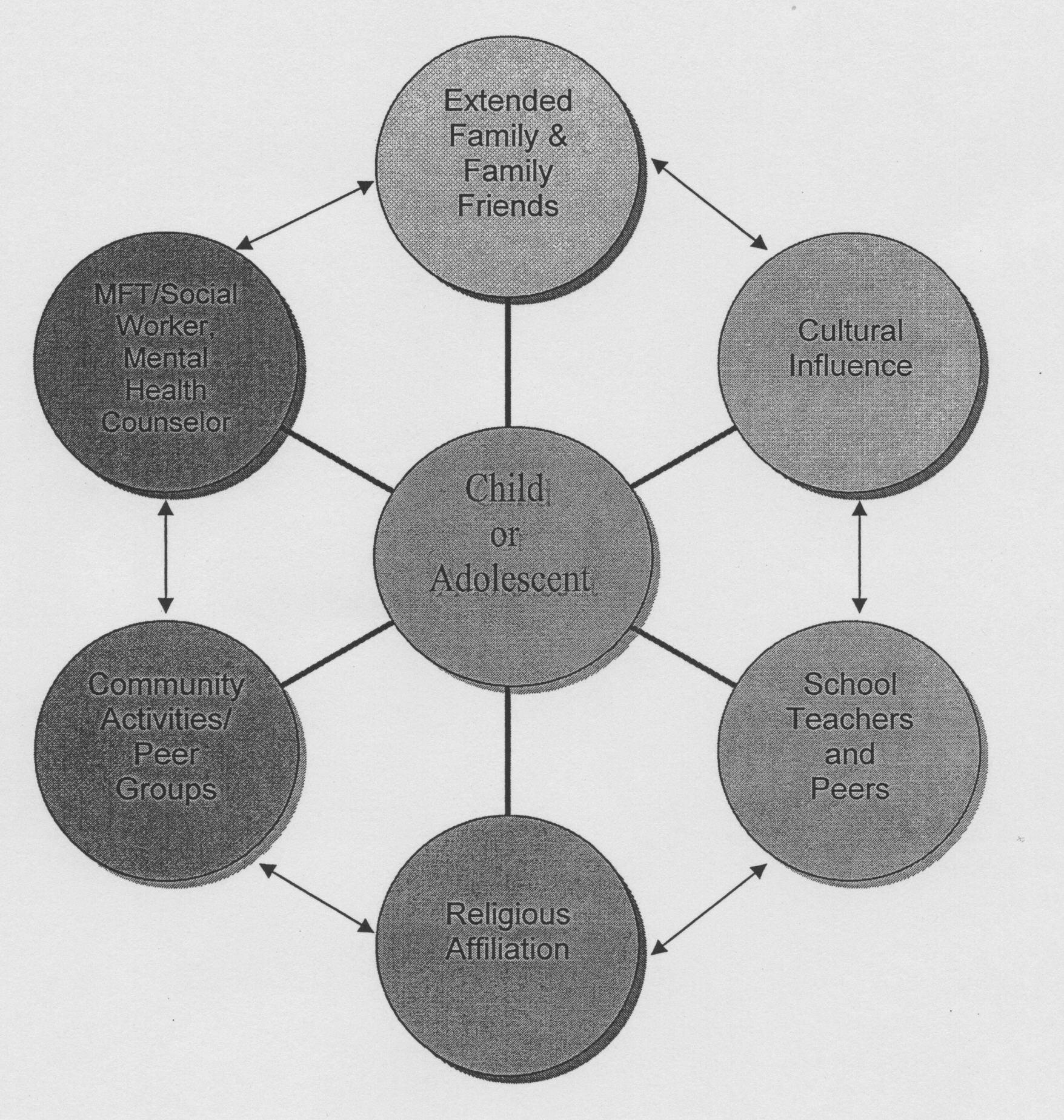

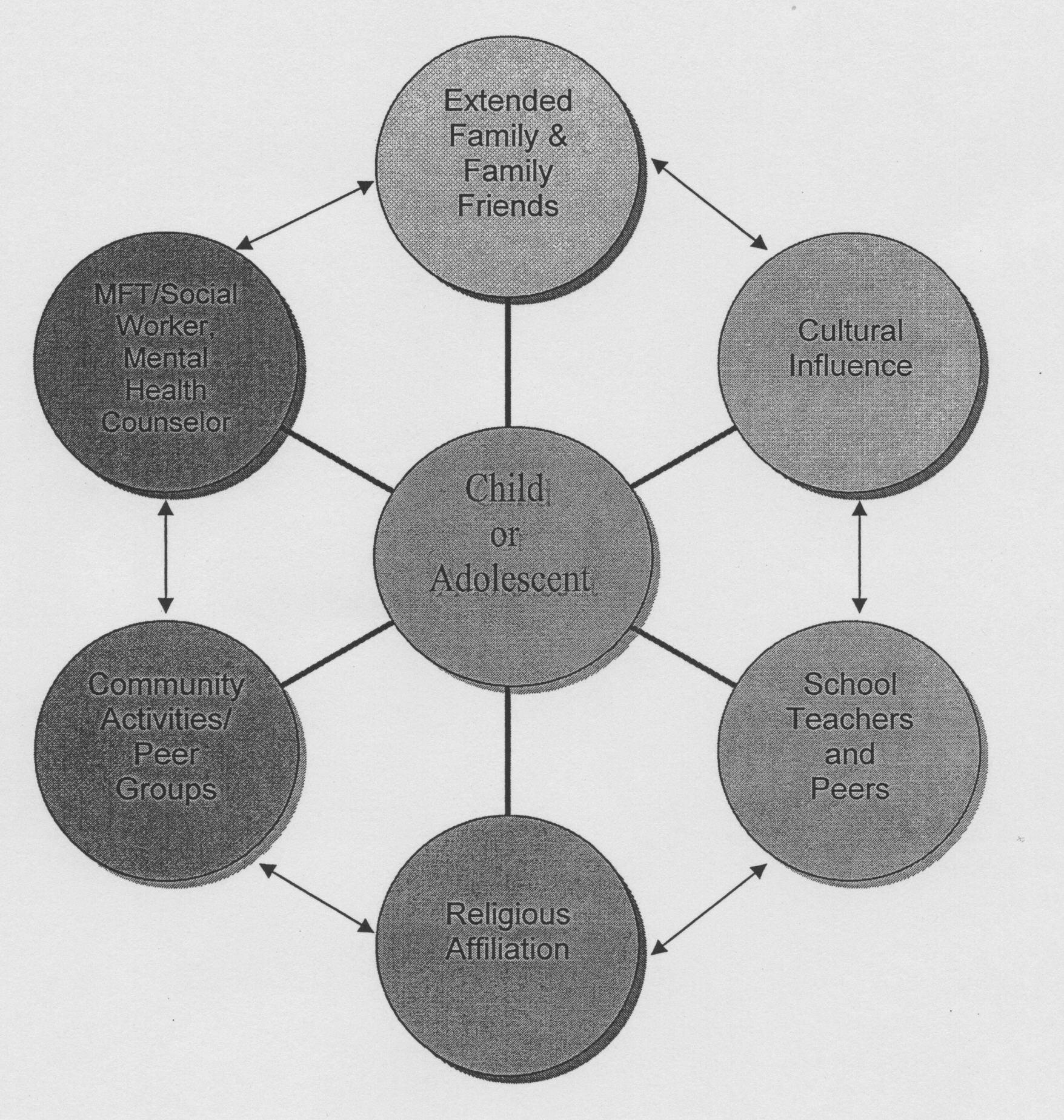

To address this issue the authors suggest that an effective intervention must be a multifaceted one that embraces all aspects of a human supportive network. One such approach can be borrowed from Whittaker's (2004), Child and Adolescent Treatment Model (CATM). The six dimensions of this model surround and support the child/adolescent and include: Professional Caregivers, Community, Church, School, Cultural Influence, and Family and friends. Most existing models offer short term intervention. The CATM however is more complete, and lays precedence for long term community wide recovery. In addition, the approach should explore and identify the level (presence) of post traumatic stress that survivors are experiencing, apply the appropriate intervention(s) and provide follow up.

According to Whittaker (2004), a systematic approach is important in working with disasters because it goes beyond the individual by examining macro-systematic social and environmental functioning. Such approach embraces the extended system within which the child or adolescent is embedded. This assertion by Whittaker (2004), is in keeping with the actions suggested by the World Health Report (2001 which proposes that all mental health interventions should: 1) provide treatment in primary care; 2) make psychotropic drugs available; 3)give care in the community; 4) educate the public; 5) involve communities, families, and consumers; 6) establish national policies, programs, and legislation; 7) develop human resources; 8) link with other sectors; 9) monitor community mental health; 10) support more research. In fact, Whittaker's Child and Adolescent Treatment Model for Crisis intervention has the potential of satisfying all of the actions stated by the world health report. The model encourages a multidimensional intervention, and is based on systems and ecological theories. The systems of intervention are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Child and Adolescent Treatment Model (CATM) by Katheryn L. Whittaker

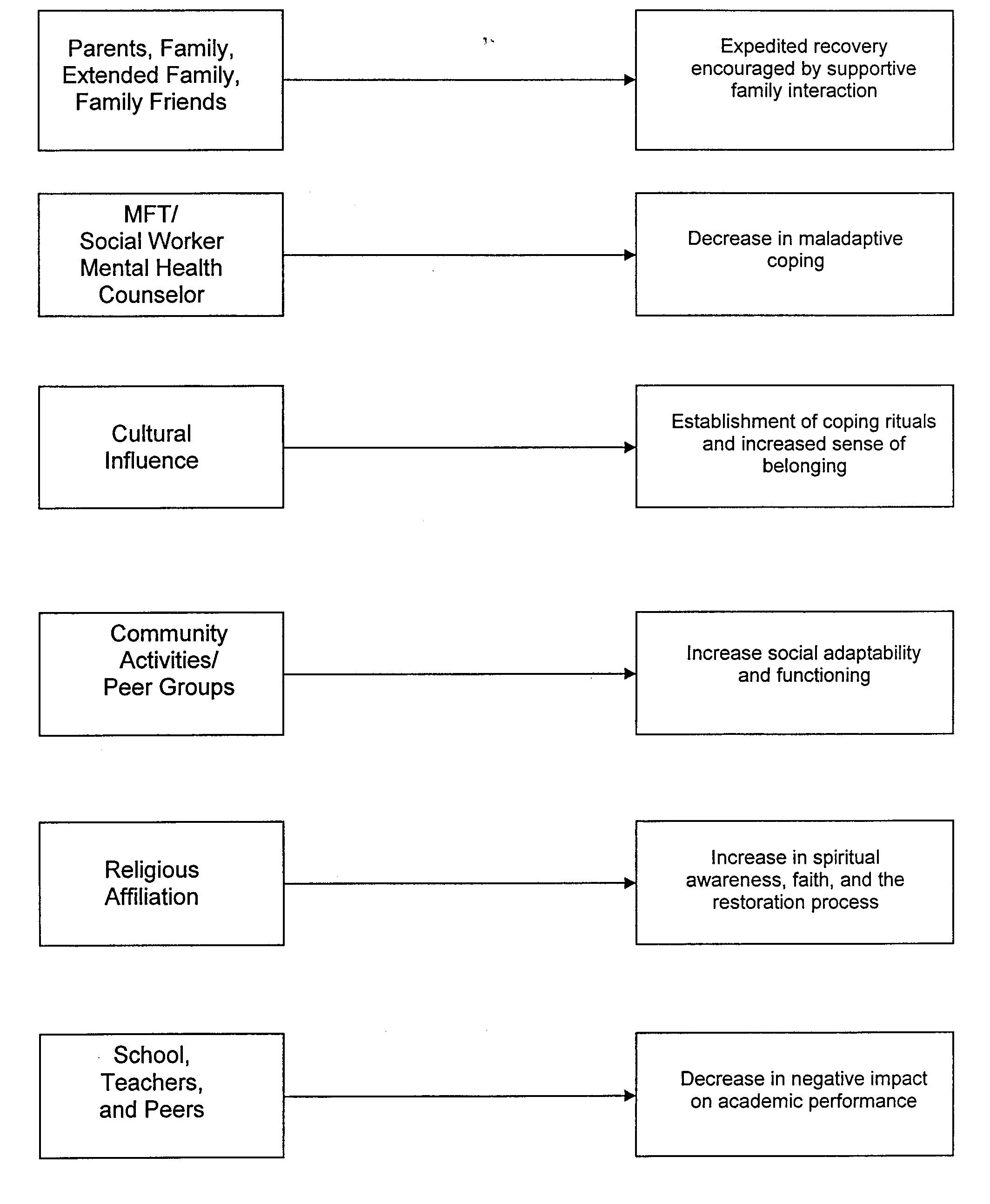

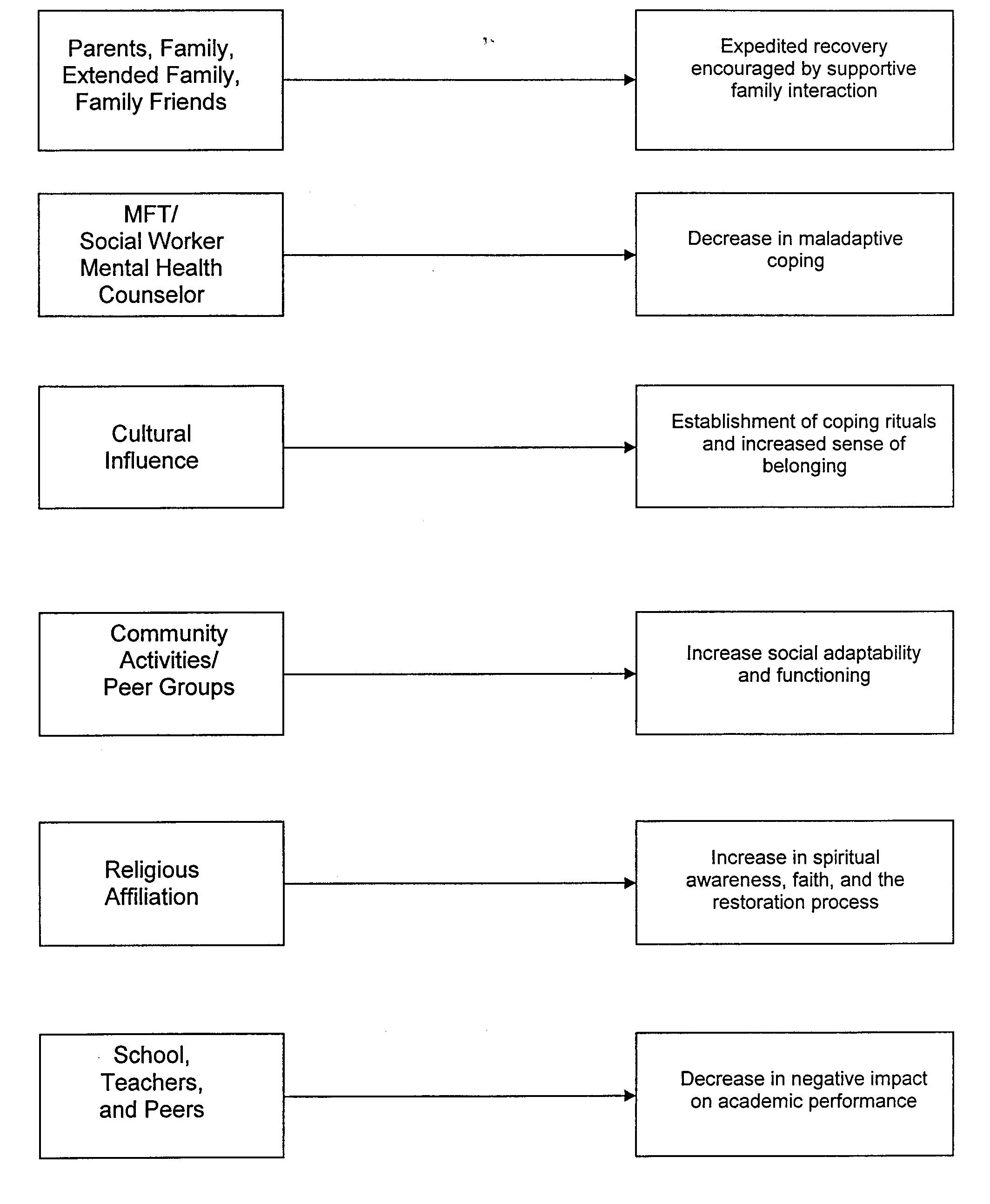

Whittaker (2004) asserted that mobilizing in each these systems could result in certain outcomes being achieved. To be specific, she purports that: a) the Parent, Family, and extended Family, and friends system is expected to expedite recovery encouraged by supportive family interaction; b) the Marriage and Family Therapy, social worker and mental health counseling system is to help to decrease maladaptive coping; while c) the outcome for cultural influence is the establishment of coping rituals and increase a sense of belonging. She further purports that the d) Community activities/peer group system is expected to promote social adaptability and functioning; while e) the Religious Affiliation system is expected to increase spiritual awareness, faith, and the restoration process. Finally the role of the school, teacher, and peers system is expected to help to decrease the negative impact in academic performance.

Clinicians are encouraged by Whittaker to adapt the CATM in ongoing work with children and adolescents recovering from traumatic events. This work is an attempt to pilot the use of this model in the Caribbean. The aim of this imitative is to develop an ongoing disaster management intervention for responding schools/universities. This approach acknowledges the university as a member of the community, and a stakeholder in the community development. It also has implications for ongoing policy development, and long term intervention support.

During the aftermath of two devastating hurricanes in 2005, The College of The Bahamas facilitated an intervention on the island of Grand Bahama. Efforts to determine the impact of the hurricanes were made using aspects of the model. Although the global conceptualization of the intervention team was the CATM, a decision was made to focus pronominally on the education system of the model. A major determinant of this decision was limited time allocated for this intervention by the organization.

Participants in the study were 107 college students and 31 employees (staff and faculty) of the Northern Campus of The College of the Bahamas. In addition 31 Guidance Counsellors of both primary and secondary school in Grand Bahama participated in the study. A group of 25 subjects from a cross section of the community and Parents Teachers Association of West End schools also participated in the study along with some of the Executive Administrative Team of the Ministry of Education in Grand Bahama. The Ministry of Education team consisted of the District Superintendent of Education, the Deputy Director of Education, the Chief Clinical Psychologist, and the president of the Guidance Counsellors' Association.

Participants completed the two questionnaires: a) A Quick Quiz for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) a 19-item instrument assessing symptoms present in PTSD and b) Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Self Quiz which is a 7-item instrument targeting symptoms related to PTSD (USA Today, 2001). These instruments functioned as a check list for the criteria for PTSD as stated in DSM_IV_TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). All respondents completed the questionnaire as it related to their personal experience. Except for the participating students, the remaining subjects completed an additional set of the questionnaires and reported on how they perceived students were responding psychologically and emotionally to the hurricane experience.

In addition to questionnaires, participants were provided with debriefing sessions. Cluster groups were also convened. From this verbal format a rich source of stories, quotes and themes emerged. These were discussed and categorized according to Donatelle's (2002) components of psychosocial health. Participants were provided with feedback from the questionnaires and the group sessions. Initial interventions were then implemented, these included individual, group modalities for personal/social /academic counselling as appropriate.

Two weeks later, follow-up sessions were provided in the form of specific group counselling sessions. Specific groups included Hospitality students, Library staff, Social work students, College Faculty, College Staff, and Students in class room settings. Additional counselling sessions were provided for individuals, dyads, and triads from these specific groups who expressed and interest. Interventions were crafted and tailored to the emerging needs of the participants.

At the completion of both phases of the intervention, meeting with both college administrators and Ministry of Education administrators we held to apprise them of the process and initial observations.

PTSD Self-Quiz: Students self report revealed that 40.66% of students were having more trouble than usual falling asleep or staying asleep; 29.67% confirmed that they had become jumpy or got easily startled by ordinary noises of movement; 26.37% avoided being reminded of the experience by staying away for certain places, people, or activities; and 21.89% felt that there was no point planning for the future. (See Fig. 2.)

Figure 2: Student self report on PTSD Self-Quiz

The Staff and Faculty of the Northern Campus in their self report indicated that 63.64% avoided being reminded of the experience by staying away for certain places, people, or activities; 59.09% lost interest in activities that were once important or enjoyable; 54.55% felt that there was no point planning for the future; and 45.45% were having more trouble than usual falling asleep or staying asleep. (See Fig. 3.)

Figure 3: Staff and Faculty self report on PTSD Self-Quiz

The Staff and Faculty perception of students' symptoms are as follows: 45.45% avoided being reminded of the experience by staying away from certain places, people, or activities; and 31.82% lost interest in activities that were once important or enjoyable, felt that there was no point planning for the future, they had become jumpy or got easily startled by ordinary noises of movement, and they had become jumpy or got easily startled by ordinary noises of movement, were having more trouble than usual falling asleep or staying asleep. (See Fig. 4.)

Figure 4: Staff and Faculty perception of students' symptoms on PTSD Self-Quiz

Students response indicated that 28% had serious problems concentrating; 27.1% were easily angered; 24.3% had insomnia; 22.4% avoided reminders of the trauma; 22.4% ruminated about the trauma; 21.5% difficulty putting life together; 20.6% had difficulty expressing thoughts and feelings, difficulty with hyper-vigilance, and trouble remembering. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5: Students Response to Quick Quiz for PTS

The Staff and Faculty self report suggested that 41.9% had trouble remembering; 41.9% avoided reminder of trauma; 41.9% had problems concentrating; and 41.9% worried about losing control if pushed. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6: Faculty and Staff self report to Quick Quiz for PTSD

The Staff and Faculty perception of students revealed 26.1% worried about losing control; 21.7% had difficulty expressing thoughts and feelings, difficulty sleeping; difficulty concentrating and were easily angered; 17.4% felt tense, nervous jumpy and cannot put life back together. (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7: Staff and Faculty perception of students on Quick Quiz for PTSD

As indicated earlier, psychosocial health status is comprised of mental health (thinking), emotional health (Feeling), social health (relating), and spiritual health (being). The participants shared stories which communicated themes that articulated the participants' psychosocial health status: 19 of the 42, (45%), reported items that fit the criteria for emotional health; 11 of the 42 items (26%) fit the criteria for mental health; while 7 of the 42 items, (17%), fit the criteria for social health; and only 5 of the 42 items, that is (12%), fit the criteria of spiritual health. This would suggest that emotional issues should be a central mobilization issue for any intervention with this group, followed by mental health and social health issues. (See Figure 8.)

Figure 8: Indicators of Psychosocial Health (Cluster Groups)

The Guidance Counsellors from both the elementary and highs schools provided self reports and perception of students for both the PTSD Self Quiz and the Quick Quiz for PTS. Their perception of students showed that among counsellors 45.2% avoided reminders of the trauma; 45.2% were jumpy and startled by ordinary noise; 38.7% had trouble with sleep and 32.3% lost interest in important and enjoyable activities. (See Figure 9.)

Figure 9: Guidance Counsellors' perception of students on the Self Quiz

Guidance Counsellors' self report on the Self Quiz revealed 54.6% had trouble with sleep; 45.2% lost interest in important and enjoyable activities; 45.2% were jumpy and startled by ordinary noise and 35.5% felt more isolated and distant from people. (See Figure 10.)

Figure 10: Guidance Counsellors' self report on the Self Quiz

Report on the Quick Quiz for PTS indicated that counsellors viewed students as struggling with 67.7% worried about loss of control if pushed; 54.8% battling with insomnia; 51.6% hyper alert and avoiding cues about the trauma; 48.4% easily angered and thinking excessively about the trauma; and 45.2% struggle with being tense, nervous and jumpy, numb at times and having no pleasure out of life. (See Figure 11.)

Figure 11: Guidance Counsellors' perception of students on the Quick Quiz

Guidance Counsellors' self report on the Quick Quiz indicated that 93.5% had problems concentrating and became easily angered; 71% battled forgetfulness; 64% worried about loss of control if pushed; 54.8% had ruminating thought about trauma and insomnia; and 45.2% struggled with trauma dreams and feeling unable to put life back together. (See Figure 12.)

Figure 12: Guidance Counsellors' self report on the Quick Quiz

The self report from students in both questionnaires indicated the presence of symptoms in all three clusters of PTSD in the DSM-IV-TR, 2000). These include a) the reliving of the event such as flash backs and intrusive images, b) avoiding reminders of the event such as activities, places, thoughts and people, and c) increase arousal with irritability, hyper-vigilance and impaired concentration. Their difficulty falling and staying asleep; being jumpy/startled by ordinary noise; easily angered; ruminating thoughts of trauma; made it logical that they experienced problems concentrating; trouble remembering things; and difficulty putting life back together. In an effort to cope they avoided being reminded of the experience; indicated no interest in planning for the future and were worry about loss of control if pushed. In their frustration and problems concentrating they became easily angered which result in difficulty in coping. These symptoms not only impaired their functioning but continued beyond a month post trauma. This suggested the presence of PTS, significant enough to require care.

Since the School as a system has as a role in disaster management of reducing the adverse impact on students' academic success, therefore faculty and staff perception of students is an important variable. The caregivers/employees perceptions of students indicated a concern about distressed students. They were particularly aware of students' propensity for loss of control if pushed too far; difficulty sleeping and concentrating. They perceived that students were avoiding reminders of trauma struggled to maintain interest and desire in planning for the future. It was also perceived that students were jumpy and easily startled by ordinary noise.

The faculty and staff are the first responders to the students. Their perception of the students as struggling with feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and fatigue, as well as the students being caught in the flight response, is important. As first responders, there is a need to develop competencies that will enable them to encourage the students who might be prone to becoming discouraged. This group has a responsibility to provide a support system that increases the likelihood that the student will re-experience a sense of safety, and prevent the student from further evolving into a spiral toward post traumatic stress disorder.

The ability of the Faculty and Staff group, as first responders, could be hindered by their own experience of post-traumatic symptoms. This group responses, like those of the students self perception, suggest that they too were significantly impacted. Among the symptoms that they experienced include; no point planning for the future; lost of interest in activities once important/enjoyable; avoiding being reminded of experience; trouble falling and staying asleep; jumpy and startled by ordinary noise; problems concentrating, worrying about loss of control if pushed; forgetful; feeling tense, nervous, and jumpy; hyper-vigilant; ruminating thoughts of trauma; easily angered; and numb feelings.

These responses suggest an experience of discouragement, and hopelessness. It may be hard to be optimistic about the future when all interest is gone and they feel so distant and isolated from others. It would also appear that they are weary from sleepiness and trying to avoid any reminder of the trauma. The presence of these symptoms could suggest a strong depressive element that needed to be monitored by a professional mental health practitioner. In addition, employees struggle with problems concentrating, remembering, and ruminating over the trauma; this may also suggests an element of depression. Their struggle with difficulty sleeping, being tense and nervous, jumpy, and hyper-alert could exacerbate a tendency to be easily angered, frustrated, and discouraged. In totality this composite picture of this group of first responders, in terms of self perception and perception of students could warrant psychological support and management.

This position is further encouraged when we compare the hierarchy of concerns for both students and employees. The students hierarchy includes 1) Trouble falling and staying asleep; 2) Jumpy/Startled by ordinary noise; 3) avoiding being reminders of experience; 4) no point planning for the future; 5) easily angered; problems concentrating; ruminating thoughts of trauma; difficulty expressing thoughts and feelings; avoid reminders of the trauma; not being a able to put life back together; hyper-vigilant; 6) use of alcohol/drugs to help me sleep or cope. The hierarchy for employees includes 1) No point planning for the future; 2)lost of interest in activities once important/enjoyable; 3) Avoiding being reminded of experience; 4)Trouble falling and staying asleep; 5)Feeling more isolated or distant from people; 6) problems concentrating; worrying about loss of control if pushed; survivor's guilt; avoiding reminders of trauma; hyper-vigilant; feel tense, nervous, and jumpy; easily angered, difficulty sleeping; trouble remembering things; and can't put life back together.

The College of The Bahamas choice in seeking candidates for the position of counselor at Northern Bahamas Campus (NBC) was influenced by the needs indicated in the data. In fact the counseling department attempted to put in place a counselor at the NBC with strong clinical skills and competencies. A counselor with a specialization in Marriage and Family therapy became priority choice in addressing the interpersonal and intra-personal issues prevalent. This addition to the counseling expertise in the NBC enables the required expertise to be in place full time as a means to develop ongoing care and supportive initiatives. Justification for hiring a counselor with strong clinical skills for the northern campus reduces the need to mobilize the counselors from the Nassau campus. The whole campus needed this support.

The response emerging from the cluster groups suggest that most of the issues for therapeutic intervention were locused in Emotional Health (feelings) and Mental Health (thinking). It is important to note that component of psycho-social health with least issues was the Spiritual Health (being). Therefore this may be perceived as the area of greatest strength, and possibly the foundation of individual and community resiliency.

If teachers are consider first line responders, Guidance counselors are the first line of defense as it relates psychosocial health. In the school setting the Guidance counselor is the only fulltime onsite direct provider of mental health related services. They form the nucleus of the internal mental health support system of the school. They are usually the initial point of internal consultation whenever any student presents with behaviors that are perceived as problematic. It is from them that most referrals are made to external mental health support systems.

As the first line mental health defense, they are central practitioners who directly initiate the schools plans around reducing the impact of disaster on academic success of students. For this reason, their PTS status is important. When taking a cross-sectional look at the PTS status of Guidance counselors in Grand Bahama, a significant traumatic state was present. Symptoms spanned all three clusters of PTSD as measured by the questionnaires. (See Figure 9 & 11.)

This significant PTS status gives rise to the question about how directly traumatized professionals can effectively provide mental health support. This is a question we need to ask when dealing also with our direct traumatized mental health social support partners, Social workers. With this in mind we turn to examine the Guidance Counsellors' perception of students. Figures 8 & 10 both illustrates a similar phenomenon to there own self perception. This could also further traumatize them as they begin to interact with what appears to be a global hopelessness state.

Results from this initiative suggested that the community was sufficiently traumatized to warrant immediate and continuous intervention. Physical, cognitive, emotional and behavioural symptoms (PTSD) were present. Given the presence of symptoms that span the entire scope of PTSD, treatment employed should be comprehensive. Treatment should address the areas of deficits for both students and caregivers. The Psycho-social Health concept is helpful in identifying the areas of health affected. The information obtained from the data will further inform the community of caregivers who are engage in crafting appropriate interventions. The CATM provides the contextual arena in which interventions are targeted. Although this study focused mainly on the school/college component, this approach can be replicated in each system of the CATM model.

It appears certain that the school community/college community was significantly traumatized. Once this level of trauma was assessed, a decision was made to assess related groups from the community who could impact the college community by their interaction with future students of the college (guidance counselors, parents from the community, social workers, and teachers). This data assisted us in advising the Ministry of Education and community stakeholders concerning the PTS status of their employees, and the perception they had of some of their students. It was hoped that this would assist the Ministry in planning an intervention that would be two fold in nature. The first aspect informed the Ministry of Education of the PTS status of their staff and students. Secondly, it served a preventive function for the college as it highlighted the needs of potential students of the college.

Similar patterns were revealed from the data generated on these caregiver groups. These finding reiterate the need for a comprehensive systems perspective on disaster management. Since one system interacts with the other and helps to foster resiliency in the community and at the individual level, we would like to propose a further development of the CATM as a model of intervention, policy generation, and community development.

Further implications for the future may include the need to evaluate subjects for past trauma experiences over the course of their lives and the effects those experiences produced. There is also a need to encourage stakeholders in each subsystem to put in place protocol that would systematically and continuously assess and treat survivors in their environment. Coordination is one of the main challenges working with a multidimensional model of disaster management like the CATM creates. In addition to coordination, some other issues that are challenging include monitoring and evaluation, and creating a protocol of intervention throughout the system. Finding the right mechanism to address these challenges require a roadmap.

Whittaker (2004) in a Policy Brief concerning the model recommends the use of a client support manual (CSM) which has a schedule for updating. We concur with the recommendation, and the suggestion that provisions be made to educate all support systems concerning the recovery process. If implemented in the Bahamas, the national emergency response initiative will be more global in scope. Inclusion of culture, will be an additive element which could promote person/system centered sensitive approaches that have the potential to assist in the development of resiliency at the individual and community level.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Barry, M. M., (2001). Promoting Positive Mental Health: Theoretical Frameworks for Practice. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 3 (1), 25-34.

Caribbean Net News, (2005). Seventh-day Adventist Contribute to Bahamas National Disaster Relief Fund [On-line], Available: http://www.caribbeannetnews.com/2005/11/23/contribute.shtml.

Drescher, K.D., Abueg, F.R., (1995). Psychophysiological indicators of PTSD following Hurricane Iniki: The Multiple sensory Interview. [On-line], Available: http://www.colorado.edu/hazards/research/qr/qr77.html.

Donatelle R.J, 2002. Psychosocial Health: Being Mentally, Emotionally, Socially and Spiritually Well. In R. J. Donattlle, Health: The Basics (5th ed., pp. 27-50). San Francisco, CA: Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company.

FEMA, (2006). Hurricane [On-line], Available: http://www.fema.gov/hazard/hurricane/index.shtm.

Ministry of Health & The Public Hospitals Authority, (2004) Department of Environmental Health Services Post hurricane Frances Assessment In The Commonwealth of The Bahamas, Post Hurricane Frances Rapid Health Needs Assessment (pp. 1-9). Nassau, Bahamas: Central Data Processing.

MOFA, (1999). Emergency Assistance to The Bahamas for Hurricane Disaster Relief [On-line], Available: http://www.mofa.go.jp/announce/announce/1999/10/1001-2.html.

The Nassau Guardian, (2004, December 15). Coping mentally after the hurricane and beyond [On-line], Available: www.thenassauguardian.com/.

USAID, (2004). Hurricane Relief [On-line], Available: http://hurricane.info.usaid.gov/.

Whittaker, K. (2006). The Impact of Disasters on Children & Adolescents: An intervention Model [On-line], Available: http://resweb.llu.edu/rford/SPOL/studentdocs/Kathi_PPT.ppt.

World Health Organization. (2001). The World Health Report 2001 Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

USA Today, (2001). PTSD Self-Quiz [On-line], Available: http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/spotlight/2001-08-03-ptsd-quiz.htm.

© Suzanne V. Newbold, Vicente Roberts, and Jose A. Velasquez, 2006.

HTML last revised 23rd November, 2006.

Return to Conference papers.