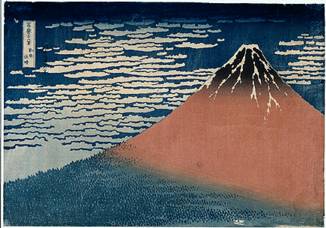

Hokusai, Mount Fuji in clear weather with a southerly breeze, c.1831.

Thanks to the Rijksmuseum for the picture

Preliminaries

What makes an issue philosophical?

Logical and empirical connections

What does all this mean for your assignment?

Instructions to students

Please make sure you read this material before we meet. In particular, the section called "Preliminaries" will be just for you to read; we won't discuss it on the system at all. The first meeting on the system will deal with the material in the section called "Education". So you have quite a lot of work to do before we start.

The material in Kleinig that roughly corresponds is his chapter 1 for my "Preliminaries" (you could also look at Appendix 1 of Argument Analysis) and his chapter 2 for "Education", but you should also look at his chapters 7 and 8 as well.

The question I would like you to ponder for the first session is: What has education got to do with preparing kids for the world of work?

What makes an issue philosophical?

Like most other social activities, the field of education and schooling is full of controversies, of arguments for or against various things, of claims that we would be better off doing this rather than that.

In many Caribbean territories there is a "Common Entrance Exam" or "11+"; but nowhere is there a consensus on whether it is a good thing or a bad one, and there is often a lot of discussion of various aspects of its operations do girls get discriminated against; do poor people get discriminated against; does it distort primary schooling; and so on. People argue about what should be in the curriculum or how it should be treated: how should English teaching be focussed; should biology discuss family planning; should there be a lot more vocational training; . Many teacher trainers advocate "discovery" methods or other types of "child-centred" teaching, while many of their trainees wonder whether such approaches are feasible in over-crowded and ill-equipped classrooms.

Those are just a few of the things people disagree about with respect to schooling. If you wanted, you could try to classify these disagreements according to their topics. But there are different kinds of disagreement as well. Sometimes people disagree about the facts: you may think butter burns at a higher temperature than corn oil; I may think it burns at a lower temperature. In simple cases we can usually work out what we are differing about and, with luck, how to settle the matter. Sometimes people disagree about tastes, or preferences, or values. You may enjoy eating tripe and beans; I don't. You may be concerned to protect and restore an old building because it is old, a vestige of a past way of life; I may want to pull it down to make room for a shopping mall. Again in these cases, we may be able to work out what our difference is. But whether or how it can be settled is often much more problematic. We are often content to leave tastes to the taster, but with some of our values we are less inclined to think that opposing positions are equally acceptable, though it is often very hard to see how to establish our own view as better than the opposition.

In the examples given just now, I assumed we all knew what was at stake; the various people we imagined had clear positions on different issues. But a lot of the time things are not so straightforward. A principal may defend the "educational" value of school uniform on the ground that it helps maintain discipline, it gives the child a symbol to be proud of, it promotes identification with the school; I may say, "So what? That's not what I want out of education. I want allegiance to be based on critical reflection and evaluation; I want original thinking to be encouraged." And the principal may agree that she too wants critical thinking, not passivity; originality, not conformity. What have we here? One answer is that we are faced with what is primarily a conceptual difficulty. Education, the goal the principal is aiming at, is being seen as simultaneously a matter of unthinking loyalties and reflective commitments; and it would seem that these two do not fit happily together. What, overall, does the principal want to achieve? There may be a clear answer, but it is going to take some finding. Or there may not be a clear answer, because her aims are intrinsically confused. Another view might be that I am the one at fault: my position is too one-sided; it assumes you can have originality without recognizing its foundation in mastery of conventional matters; that you can reflectively commit yourself without first having learnt what unreflective commitment is.

On either answer, we have found ourselves in a quagmire. To make any progress we are going to need to distinguish different issues, and to explore how these different issues connect with each other. The words we had previously used, the terms of the debate, are themselves going to come centre-stage. Is the principal's view of education as made up of these various things coherent? Do we want to say that Mr X, none of whose pupils passed the exam, was actually teaching them? Do people exhibit intelligence in as much as they can go for a walk without knocking into things, unlike most robots we have managed to build? There may be factual and evaluative differences mixed up with these questions (there almost always are in the ones we shall be looking at) but what I am claiming distinguishes them is the way they push us to reconsider the terms of the debate, how we frame the questions. We recognize that we do not have a clear grasp of what the issues are, so we have to step back and begin the job of sorting out the conceptual connections we were previously relying on without explicit awareness. (What I am getting at is that conceptual connections are there all the time but do not usually call attention to themselves; if we call something a "vestige" of a past way of life, we suggest that there are not many other examples to be found, but both the antiquarian and the developer use the word "vestige" in the same way, so we need not attend to its connections.)

One sort of philosophical issue arises when we are faced with the sort of quagmire just described. We are pushed away from asking whether X is good, bad, or indifferent to asking whether we should call it "X" in the first place. We recognize a need to consider explicitly how X is linked to Y and Z. We want a map of the conceptual terrain, which I hope explains the title I have given these notes.

Another kind of philosophical question (which may very well overlap with the first) arises particularly when we try to explain and clarify our values. The languages we use have ways of categorizing the physical world and the social, interpersonal world. We employ scientists to improve, modify, and sometimes replace our categories and guidelines for describing and understanding the physical world. We can get by thinking that things expand as they get hotter, especially if we remember the odd exception like water becoming ice;1 but if ever we need accuracy we turn to the physicists and chemists to tell it like it is. But we do not really have a counterpart to the scientist when it comes to our ways of categorizing, explaining, and judging each other. We think it is wrong to tell lies, but most of us will agree to some exceptions (for instance, Plato's example of a homicidal madman asking where you put his dagger) and there will be strong disagreements on other cases. But we do not have anyone to turn to for an authoritative answer. One of the tasks of philosophy is to help fill this gap; not by offering authoritative answers so much as by trying to clarify and make explicit the principles we are already using implicitly, or by taking some plausible general principles and remodelling our thought along those lines.

It might be worth noting that lawyers and theologians are also engaged in a similar business of following out the implications of certain general principles of conduct, though they tend to begin with somewhat idiosyncratic assumptions. Some people may think that gurus give authoritative answers to the sort of questions we are looking at here; but typically gurus do not make their reasoning explicit, and it is difficult to discern authority when there are so many discrepant voices.

So I'm suggesting that there are at least two sorts of question that fit under the umbrella of "philosophy": those that arise when we try to put our evaluative house in order, when we try to make explicit and coherent the grounds we have for some of our policies and practices; and those that arise when we find the terms we use begin to get in our way, when we need to rethink the criteria for something to count as an X or precisely how X connects with Y.

Logical and empirical connections

Let's try another view of the subject. Earlier in this century, English-speaking philosophers used to think they could distinguish clearly between logical or conceptual connections on the one hand and empirical connections on the other. And they went on to say that philosophy was only concerned with the logical connections. Nowadays many philosophers are suspicious of this old distinction (Kleinig, for instance, refrains from using it explicitly: p. 152; and my discussion here glosses over many nuances we should distinguish in a more advanced account), but something of its spirit remains in what they choose to talk about. It remains in the way I talked above about getting into a quagmire with certain issues, a quagmire that demands philosophy rather than psychology or sociology, say, to get us out.

Let us try to get a feel for the distinction. One of the meanings of the word "bachelor" is an unmarried adult male. Given that, you don't need to do much to know that all bachelors are unmarried. But suppose someone suggested that all bachelors had domineering mothers. To decide whether to accept or reject that you would have to do something; you would have to start checking bachelors. To take another example, suppose someone said all mountains are snow-capped. Well, Everest is, and Kilimanjaro is, but look at the Blue Mountain Peak in Jamaica; that's a mountain, but it's not got any snow on it, so the claim is false. The claim suggested that there was an empirical connection between being a mountain and being snow-capped; but that connection does not hold in every case. When you have to examine how things are in the world, checking on mountains or bachelors or whatever, then the connections you are dealing with are empirical ones; but when you don't need to look at cases but can simply work it out from what the words mean then you are faced with logical or conceptual connections.

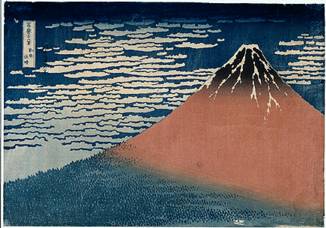

As we saw in Argument Analysis, when we are dealing with logical connections it is not just a question of how things are but of how they must be. You do not merely not find any married bachelors; you couldn't find any. Even if every mountain on earth did have a snow cap, there could still be one that didn't; such a thing would be possible, even if not actual, so the connection would be merely empirical (or to use another bit of philosophical jargon, contingent). And as we saw then, this contrast needs some care. In a flat Euclidean space, the interior angles of a triangle must sum to two right angles; Descartes once said that in the same way, mountains were accompanied by valleys. But you could have a mountain just stuck up above a flat plain, like drawings of Mount Fuji, so once again the connection is not logical or conceptual.

Hokusai, Mount Fuji in clear weather with a southerly breeze, c.1831.

Thanks to the Rijksmuseum for the picture

When we are investigating an empirical connection, we know we have to follow the procedures of the field in question. If the connection is historical, we do what historians do; if it is a matter of chemistry we follow the chemists; if it is a matter of psychology, we can hope that the psychologists have got a way of helping us. The investigations may be difficult; they may be impossibly difficult, given our present understanding of the topic; but at least we know the sort of thing we should do, the sort of evidence that would help us. Take the fact that sometimes perfectly healthy babies just die in their sleep. Someone thinks it is a cultural matter, a reflection of differing child-care habits and expectations; someone else thinks it is a matter of exposure to abnormal electromagnetic fields. We don't know; but we may hope to be able to recognize which answers work and which don't. We have a problem; we have a variety of ways of tackling it. One day we may have some answers. We don't here have the kind of quagmire I talked about in the previous section, even though it is quite possible that investigations will reveal a need to change our concepts (we may find, for instance, that such deaths fall into several distinct groups, with quite different explanations). The issue is purely empirical.

The problems philosophers talk about are typically not like that. We are not going to get the answers by doing a bit of historical investigation or some psychological experiments. Matters of logic, of the coherence of our concepts, have to be thought out. Similarly, matters of value, of the ordering of our priorities, require us to reflect.

Progress and lack of progress

In many branches of empirical enquiry we seem to make progress. We know a lot more about the sun than did Ptolemy or Copernicus. We may even have a fuller understanding of the Peloponnesian War than Thucydides had. But in the areas philosophers deal with, it seems that much less has been achieved. If I were trying to defend philosophy, there is quite a lot to be said about these appearances; but at the moment I merely want to indicate one factor that contributes to the apparent irresolvability of many philosophical discussions.

In general we test claims by putting forward other claims; we recognize that we cannot keep all of them. I say "all mountains are snow-capped"; you say "Blue Mountain Peak is a mountain and it doesn't have any snow." Very schematically, we can't have both "A" and "B"; we can't have our cake and eat it. Now when that's our situation, we always have two options: we can keep the cake and not eat; or we can eat and not keep the cake. One reason for the success of many empirical disciplines is that they incorporate usually unquestioned conventions for "deciding" which of the options to take. When I've climbed to the top of Blue Mountain Peak and not seen any snow, I don't really have the option of keeping my original claim that all mountains are snow-capped. I can't say "it's only a hill," or "the snow is very thinly scattered." But with the topics philosophers tend to discuss, things are not so straightforward; l might prefer to keep the cake and not eat; you might prefer things the other way round. We can both recognize the incompatibility, but there is no consensus on how to handle it.

This point is one reason for my using "A Logical Geography" in the title to these notes: I hold on to some connections while cutting others; another writer might make a different selection. There is also another reason: maps are made with different purposes in mind, and may be very different from one another because of those purposes. My main purpose is to help you think more clearly about various issues (and to make it easier for you to see things my way); someone else might be more concerned with capturing the language use of a particular community. There is even a third reason: even when we share a reason for drawing a map, we may still differ over precisely how to draw it, the theories or general principles we are going to use (in the case of actual maps, we may, for instance, differ over the kind of projection we adopt). In philosophy there are different ways of displaying conceptual connections, so what I offer you is only one way among others of doing the job.

What does all this mean for your assignment?

You are probably totally confused by now. You are about to start a course in a subject where there are no answers, and apparently few guidelines about how to tackle the unanswerable questions. So how can you know what I'm looking for?

That may not be an unfair question; but there are a couple of things you might be able to extract from what I've said above. One thing is that if you think the way to answer a question is simply to tell me what goes on, how you teach or what the policy is in your territory, then you've probably missed the point. If you think you can answer the question by telling me the "findings" of your favourite discipline, again you've probably missed the point.

A second thing you can work out is that I'm not interested in whether you share the same final position as I accept. What I am concerned about is that you recognize the logical or conceptual connections, what goes with what; but as I was saying just before: you may want to eat the cake, and I may want to keep it; no problem.

I should add here that I'm not concerned whether you have any position at all on the topic you are discussing. One thing that can happen to you when you start philosophizing is that you start by wanting to eat the cake (in fact you probably start not even recognizing that there is any question of doing anything else) and then, when you read around and reflect, you may see that there is an equally good case for keeping it. So you end up not knowing which side to support. Again, as far as your work for me goes, no problem. What does matter is your recognition of the "problem situation," the way the issues connect, what can be said for and against the various conflicting positions.

(If you find the preceding possibility fulfilling itself in your head, please don't leave your essay as a piece of "stream of consciousness." You should always plan what you are going to write, so you know at the start how you are going to end up, and can then present everything from one coherent point of view. The point I am getting at is that "There are good grounds for A, and equally good grounds for B, and no problems that are obviously greater for one rather than the other" is a coherent point of view from which to organize your discussion.)

OPTIONAL EXTRA: Philosophy

The tradition of enquiry you are joining is about 2,500 years old. Much has happened to it in that time, and it has many branches which will not impinge on our activities. It is foolhardy to try to summarize what philosophy is when it has such a history, but in case you want to get a broader view of the subject I am offering you an extract which describes (from one contestable point of view) what philosophy looked like at the start (a group of thinkers known collectively as the "Presocratics"):

According to tradition, Greek philosophy began in 585 BC and ended in AD 529. It began when Thales of Miletus, the first Greek philosopher, predicted an eclipse of the sun. It ended when the Christian Emperor Justinian forbade tile teaching of pagan philosophy in tile University of Athens.

What are the characteristics that define the new discipline? Three things in particular mark off the phusikoi from their predecessors.

First, and most simply, the Presocratics invented the very idea of science and philosophy. They hit upon that special way of looking at the world which is the scientific or rational way. They saw the world as something ordered and intelligible, its history following an explicable course and its different parts arranged in some comprehensible system. The world was not a random collection of bits, its history was not an arbitrary series of events. Still less was it a series of events determined by the will or the caprice of the gods. The Presocratics were not, so far as we call tell, atheists: they allowed the gods into their brave new world, and some of them attempted to produce an improved, rationalized, theology in place of the anthropomorphic divinities of the Olympian pantheon. But they removed some of the traditional functions from the gods. Thunder was explained scientifically, in naturalistic terms it was no longer made by a minatory Zeus......

It is in the development of the notion of explanation that we may see one of the primary features of Presocratic philosophy. Presocratic explanations are marked by several characteristics. They are internal: they explain the universe from within, in terms of its own constituent features, and they do not appeal to arbitrary intervention from without. They are systematic: they explain the whole sum of natural events in the same terms and by the same methods.... Finally, they are economical: they use few terms, invoke few operations, assume few 'unknowns.'.... If their attempts sometimes look comic when they are compared with the elaborate structures of modern science, nonetheless the same desire informs both the ancient and the modern enideavours the desire to explain as much as possible in terms of as little as possible.

Science today has its own jargon and its own set of specialized concepts mass, force, atom, element, tissues nerve, parallax, ecliptic and so on. The terminology and the conceptual equipment were not god-given: they had to be invented. The Presocratics were among tile first inventors. .... It cannot be said that the Presocratics established a single clear sense for the term logos or that they invented the concept of reason or of rationality. But their use of the term logos constitutes the first step towards the establishment of a notion which is central to science and philosophy.

The term logos brings me to the third of the three great achievements of the Presocratics. I mean their emphasis on the use of reason, on rationality and ratiocination, on argument and evidence.

The Presocratics were not dogmatists. That is to say, they did not rest content with mere assertion. Determined to explain as well as describe the world of nature, they were acutely aware that explanations required the giving of reasons. This is evident even in tile earliest of the Presocratic thinkers and even when their claims seem most strange and least justified. Thales is supposed to have held that all things possess 'souls' or are alive. He did not merely assert this bizarre doctrine: he argued for it by appealing to the case of tile magnet. Here is a piece of stone what could appear more lifeless? Yet the magnet possesses a power to move other things: it attracts iron filings, which move towards it without the intervention of any external pushes or pulls....

The argument may not seem very impressive: certainly we do not believe that magnets are alive, nor should we regard the attractive powers of a piece of stone as evidence of life. But my point is not that the Presocratics offered good arguments but simply that they offered arguments.

It is important to see exactly what this rationality consisted in. As I have already indicated, the claim is not that the Presocratics were peculiarly good at arguing or that they regularly produced sound arguments. On the contrary, most of their theories are false, and most of their arguments are unsound. (This is not as harsh a judgement as it may seem, for the same could be said of virtually every scientist and philosopher who has ever lived.) Secondly, the claim is not tile Presocratics studied logic or developed a theory of inference and argument.... Nor, thirdly, am I suggesting that the Presocratics were consistently critical thinkers.... Although we may talk of thee influence of one Presocratic on another no Presocratic (as far as we know) ever indulged in the exposition and criticism of his predecessors' views . Critical reflection did not come into its own until the fourth century BC.

What, then, is the substance of the claim that the Presocratics were champions of reason and rationality? It is this: they offered reasons for their opinions, they gave arguments for their views. They did not utter ex cathedra pronouncements. Perhaps that seems an unremarkable achievement. It is not. On the contrary, it is the most remarkable and the most praiseworthy of the three achievements I have rehearsed. Those who doubt the fact should reflect on the maxim of George Berkeley, the eighteenth-century Irish philosopher: All men have opinions, but few think.

Jonathan Barnes, Early Greek Philosophy, Penguin, 1987, pp. 9-24

Barnes identifies a demand for rationally acceptable explanations of the world as central to philosophy and science. One thing we can say is that as we have discovered ways of dealing with limited parts of the world we have evolved special disciplines (mathematics; chemistry; history; ...) to investigate those aspects. One remaining task of philosophy is to try to put these specialized accounts into a synoptic whole; to try to see how our natural sciences can fit with our understanding of ourselves, for instance.

The demand for something rationally acceptable quickly makes one reflect on what should count as rationally acceptable. And so, from early on, philosophers found themselves dealing directly with questions of loqic of meaning (unfolding conceptual connections of the sort we looked at earlier), and of what is involved in knowledge. These, especially logic, have become specialized disciplines in their own right, but they remain essential adjuncts to the task of getting a rationally acceptable overall picture.

The philosophers Barnes is talking about are named from the fact that they lived and worked before Socrates. He made explicit the other permanent feature of philosophy, a concern not just with the universe as it is but with how human life ought to be, our moral and political values. So the two types of philosophical issue I described earlier (conceptual clarification and reflection on evaluative principles) have a long and distinguished history in the subject.

Most of the topics we shall be looking at in this course fall under the umbrella of conceptual clarification, though important moral questions often crop up in our reflections. But the final topic we shall look at, religious education, is mainly a matter of sorting out our evaluations about schooling and the content of the curriculum.

1 I am glad to learn that my example betrays serious ignorance of what happens when water turns to ice; in the change of state, it does not get any colder though it does expand; apparently it expands from 4°C hotter or colder. I have managed to get by with such ignorance for a good many years, as the text says. Thanks to Peter Whiteley for pointing out my error.

URL http://www.uwichill.edu.bb/bnccde/epb/stepsprelim.html

© Ed Brandon, 1992, 2001. HTML prepared using 1st Page 2000, last revised June 18th, 2001.